Chinese Poetry

Chinese poetry is something well worth exploring. While English speakers look back to the time of Shakespeare and Milton 400 years ago as a Golden age, Chinese look back far further, to the Tang dynasty 1,200 years ago as their Golden age of literature. The longevity of the language has much to do with the continuous poetic tradition. Chinese poems written a thousand years ago still read fresh and modern and this is because the language has changed so little. Poetry has remained a popular literary form in China for centuries and Chinese people will often know poems by heart. Many have had a go at writing poems themselves including political leaders like Chairman Mao.

As Chinese characters are not principally phonetic, changes in the manner of speaking have not affected the impact of poems as has happened in other languages. Chaucer ➚'s English is barely readable after 600 years. However, there have been changes, and sometimes the Chinese rhythmic structure has been lost as well as some of the characters that have fallen out of use over the centuries.

The oldest known work of poetry is the Shijing 诗经 ‘Book of Odes’ which is a collection of poems covering four hundred years in the Zhou dynasty (2,500 years ago). This work is also known as the ‘Book of Songs’ as they were written to be sung rather than read. It is the oldest of the ancient classics to have survived.

Qu Yuan was the first known poet of the late Zhou. In the early Han dynasty Sima Xiangru established the long-standing 赋 ‘fù’ style based on Qu Yuan's in the form of rhymed prose. This style was followed by Ban Gu ➚ among others. In the Period of Disunity Cao Zhi (a son of Cao Cao) developed a new style and Daoism influenced the subject matter as in 阮籍 咏怀诗 Ruǎn jí Yǒng huái shī ‘The Heart Unburdened ➚’. Another important work comes from the 6th century 文心雕龙 Wén xīn diāo lóng ‘The dragon-carving of a literary mind’ by Liu Xie ➚.

An astounding 48,000 poems have survived from the many Tang dynasty poets. It is considered that Cantonese the language of southern China is closer to the spoken dialect when poems were created in the Tang dynasty. After that time, poetry became rather stultified, because the ancient tradition was so admired and well established that poets struggled to establish a modern style that was not rooted in the glories of the past. However the 词 Cí style of the Song dynasty did become a popular form that was more fluid and less regimented than that of the Tang.

A key attribute of Chinese poetry is that it is concise, each character places a thought, an impression, an image. There is no need for formal grammar and the small words like in, the as well as ‘verbs’ are generally missed out. Emphasis is put on use of rhythm and also on the balanced look of the characters on the paper. A reader assembles the series of impressions into a whole piece in a very direct way compared to speech. Many poems contain allusions to people and events from Chinese history, and that makes understanding these poems a challenge to non-Chinese. Translating Chinese poems into English poses all sorts of problems and many eminent American and English poets (for example Ezra Pound ➚) have spent considerable time writing fine translations. Writers have tried to convey the spirit of poems in their own individual ways. Although much is lost in translation the core meaning can be greatly appreciated.

Qu Yuan 屈原 [343 BCE - 278 BCE] or Ch'ü Yüan WG

Qu Yuan is best known for his connection with the Dragon Boat Festival. He was a statesman and poet of the Warring States period (about 2,500 years ago). He wrote some of the earliest known poems including elegies. His poems were the first to be attributed to an individual writer, up until then poems were published as anonymous collections. His most famous poem Li Sao 离骚 ➚ ‘Encountering Sorrow’ alludes to his falling out with the King of Chu. Later, when Qu Yuan was falsely slandered by a prince he decided to take a stand for the truth and committed suicide. He came to represent the laudable qualities of incorruptibility and loyalty.

According to legend when he drowned himself in the Miluo river, the people of Hunan went out in boats to look for his body. The Dragon Boat festival commemorates this event. The festival had however already been instituted to make annual offerings to the dragon kings to bring rain for the summer crops. The lack of definite details about his life has led some to link his suicide to a battle where the state of Chu was defeated by the army of the Qin kingdom in 278BCE.

Wang Wei 王维 [699 - 759]

Wang Wei was a leading Tang poet and painter. Born into an aristocratic family he passed the important jinshi examinations to become a senior court official in 721. Music and painting were among his many accomplishments and it was as a musician that he received his first post at court. Wang Wei was banished because of some minor breach in etiquette and then traveled through the country being gradually promoted through a series of official positions. He owned a house in the hills 30 miles [48 kms] from the then capital of Chang'an. The An Lushan rebellion destroyed his career prospects and it was only around 759 that he was restored to his previous post. He is best remembered for poems that describe landscape and for his paintings of the countryside.

Wang Wei's work bears the imprint of his Buddhist views as nature and landscape feature heavily. The poems are often short (4 lines of 5 characters) and give an impression of a static scene rather than transformation. His poem ‘Spring Stream’ is typical of his style:

鸟鸣涧

人闲桂花落夜静春山空

月出惊山鸟

时鸣春涧中

Mountain stream birdsong

Li Bai 李白 [701 - 762] or Li Po WG

Li Bai together with Du Fu are considered the greatest of the Tang dynasty poets.

Eleven years older than Du Fu, Li Bai, also known Li Po, was born north of China and moved to Gansu and then to Sichuan when a young child. Li Bai's grandfather was also a well-known poet. He is considered by some to have been named after the planet Venus as 李太白 Lǐ tài bái. He proved to be an able student but never took the examinations to become a government official. From Sichuan he traveled down the Yangzi River to visit friends. In 742 on the recommendation of a Daoist priest he was summoned before the Emperor Xuanzong. The emperor was impressed by his knowledge and philosophy and gave him an official position. He was eventually banished from court having upset the famous concubine Yang Guifei and then backed the wrong prince in the An Lushan uprising. He was lucky to escape with his life and was banished to remote Yunnan. Eventually his banishment was annulled and Li Bai settled down in the Nanjing area.

In style he went beyond the rules laid down by previous poets, often writing about drinking and drunkenness. His poems seem rooted in the everyday life of ordinary people.

Du Fu 杜甫 [712 - 770] or Tu Fu WG

Du Fu stands out as one of the greatest of Chinese poets. Born in 712 close to Luoyang in Henan his ancestors were minor officials. Du Fu sought to follow tradition by entering the Imperial service. For many centuries this meant a grueling study of Confucian classics to be tested in the Imperial examinations. Because of political and stylistic considerations he did not pass the examinations as candidates were scored for precise recall of the classics and not for creativity.

In 744 he met the great Tang poet Li Bai and this spurred Du Fu's to commit himself fully to poetry. Li Bai was eleven years older and the relationship was one of student and master rather than equals. In 755, he made use of connections at court to be appointed as a minor official. External events blew away his career path as the An Lushan rebellion broke out; after that his life was a series of short appointments at different locations, most importantly at Chengdu, Sichuan where his thatched hut can still be visited. His work was not much appreciated during his lifetime or for a couple of centuries after his death.

Stylistically his work unites poet and nature, actions in nature interplay with the emotions of people. His poems are rooted in every day life with a somewhat positive outlook.

See below for a Du Fu poem and its translation

Su Shi 苏轼 [1037 - 1101] or Su Shih WG

Su Shi also known as Su Dongpo 苏东坡, arguably the greatest poet of his time, was born into a literary and wealthy family in Meishan, Sichuan. He excelled at his studies to pass the Jinshi examinations at the young age of 19 and soon became a protege of Ouyang Xiu ➚ 欧阳修. Su Shi took up government positions at various locations. Like many Northern Song dynasty scholars he had many accomplishments apart from poetry, he worked as an engineer, statesman, philanthropist and was considered a great tea connoisseur. A piece of his calligraphy (Han Shi Tie 寒食帖 ➚) takes pride of place at the National Palace Museum, Taipei.

A poem ➚ criticizing Wang Anshi led him to be exiled to Huangzhou, Hubei. Here he lived in poverty tending a small farm, it is here that he took the literary name ‘Dongpo’ meaning Eastern Slope. On the fall of the Wang Anshi faction in 1086 he was summoned back to court before being banished again to Huizhou, Guangdong and then the island of Hainan. Although pardoned in 1100 he died on the way to take up a new post. Even though his work was banned for decades after his death 800 letters and over 2,700 poems have survived.

The heritage of the Tang poems written 300 years previously can be seen in his work. Song poets wrote voluminously and the style is more expansive than their more famous predecessors. He wrote mainly in the 词 Cí style. This style was sung rather than recited at banquets and gatherings. He is known collectively with his father and brother as one of the Great Three Su poets. Changes in his circumstances required frequent moves and so travel is a recurring theme in his work. Contemplation of exile and the lack of challenging work add a bitter edge to some of his poems.

Bai Juyi 白居易 [772 - 846] or Po Chü-i WG

One of the most widely revered and read Chinese poets is Bai Juyi, he was another poet from the golden age of the Tang dynasty. His influence has spread to Korea and Japan. He was born in Taiyuan, Shanxi in 772 to a poor but scholarly family, a little time after the great Tang poets Li Bai, Du Fu and Wang Wei. To avoid the wars in northern China he moved south to Jiangsu province in 782. He succeeded in the Civil Service Examinations to reach the grade of jinshi enabling him to serve as a well-paid government official.

Bai Juyi rose to be a minor court position by 814 but then broke protocol in his writings and was banished to Jiujiang in Jiangxi province. He went back briefly to the capital Luoyang before being appointed governor of Hangzhou. In 825 he was made governor of the rich city of Suzhou. After a period of semi-retirement he moved in 832 to the Longmen Buddhist caves close to Luoyang in Henan where he died at the venerable age of 74. He is remembered for his simple, readable style covering everyday life. He was later criticized for the vulgar, populist style of his work but they retain popular appeal. Here is an example:

Song of the Palace

泪尽罗巾梦不成夜深前殿按歌声

红颜未老恩先断

斜倚熏笼坐到明

‘With a handkerchief wet with tears, she can not sleep;

It is deepest night before the noise of Palace voices stir;

Although her rosy cheeks are still fresh, she is no longer a maiden;

Sitting wreathed with smoke she waits the new day.’

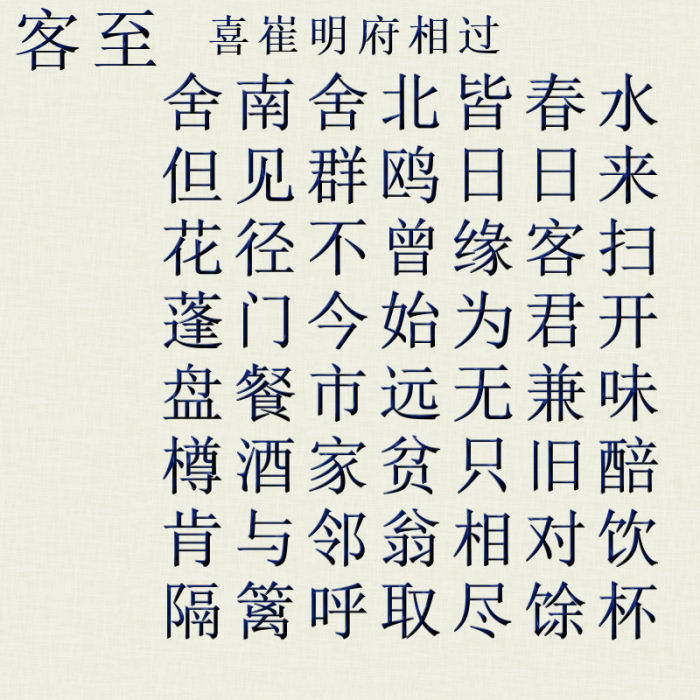

A Visitor Arrives - a poem by Du Fu

The poem studied here is ‘A Visitor arrives’ by Du Fu. It was written about 760CE after the poet moved to his famous thatched hut ➚ that can still be visited near Chengdu, Sichuan. We have chosen this poem because it lacks the historical allusions that are present in many Tang poems which are difficult to convey to a modern audience. Often they mention a place, a person or an event in Chinese history which to a Chinese will immediately give a rich context but this is lost on the rest of us.

A poem can even use the shape of characters to give a visual style. As in English it will often use rhymes at the end of lines to give structure. In this case there is a repeated ‘ei’ sound on alternate line endings. All eight lines have seven characters, making a pleasing regular shape on the paper. This is an example of the Jintishi ➚ 近体诗 regular form for a shi poem ➚ and there is a pattern to the tones on the characters as well as the overall structure.

However, a lot of changes have crept in over a thousand years. Some of the modern 'simplified' characters are not the same as the ones Du Fu would have known and used. Pinyin uses the Beijing dialect and just as with Shakespeare, pronunciation has changed (if indeed Du Fu used the Mandarin dialect). Careful analysis requires taking all this into account, and all that is beyond this short introduction.

Here is the poem laid out with a Chinese character font and underneath the pinyin representation.

kè

zhì

xǐ

cuī

míng

fǔ

xiāng

guò

shě

nán

shě

běi

jiē

chūn

shuǐ

dàn

jiàn

qún

ōu

rì

rì

lái

huā

jìng

bù

céng

yuán

kè

sǎo

péng

mén

jīn

shǐ

wèi

jūn

kāi

pán

sūn

shì

yuǎn

wú

jiān

wèi

zūn

jiǔ

jiā

pín

zhǐ

jiù

pēi

kěn

yǔ

lín

wēng

xiāng

duì

yǐn

gé

lí

hū

qǔ

jìn

yú

bēi

English Translation

Translating an ancient Chinese poem into English is not an easy task, quite apart from the very different type of language and the age of the poem there are all sorts of decisions to make. Do you go for an accurate transcription, where each character in Chinese is represented in English by words in roughly the same order? Or do you use modern English to try to capture the spirit of the poem?

The first step is to work out the English meaning of each character. If you just look up each character in turn in a dictionary then you end up with something much like simple software translation software would produce - gibberish. Well may be gibberish with a few hints as to the intended meaning as you can see from the following.

Visitor

until

Happy

cui

bright

mansion

mutually

past

hut

south

hut

north

all

spring

water

but

see

flock

gull

day

day

arrive

flower

footpath

not

previously

cause

visitor

sweep

Disheveled

gate

now

begin

for

gentleman/lord

open

Helpings

supper

market

far

nothing

twice

taste

Vessel

wine

home

poor

only

old

unstrained spirits

Agree

give

neighbor

old man

mutually

with

drink

divide

hedge

call

take

use up

remaining

cup

This is all a bit artificial as you would not use the first modern meaning in the dictionary, in place of the historically accurate one. You can see that a simple transliteration is not very good. Now let us take each line in turn, coming up with a more reasonable translation.

Title. 客至 (喜崔明府相过)

A Visitor Arrives: A friendly welcome to Vice Prefect Cui

The subtitle gives the clue that the guest in question is an official. The translation of an ancient title for the official is tricky, so you have to take this on trust.

1. 舍南舍北皆春水

My hut is surrounded by spring waters

The opening line sets the scene. The poet's hut is nearly flooded by spring water. It immediately gives an image of an isolated building battered by the elements. The fact that it is spring suggests the situation is changing and should improve.

2. 但见群鸥日日来

All day there have only been circling gulls in the sky

The second line adds another more detail to the situation, it indicates he has been isolated for some time as all he has seen are gulls. The pinyin for gull is ‘ou’ the sound of its plaintive call echoing down the centuries. Gulls are not the friendliest of birds and are usually seen only at a distance. He would have given a different impression if he had seen a sparrow. The repetition of ‘day’ seems to be stressing the emptiness of the day.

3. 花径不曾缘客扫

There’s little point in sweeping the garden path for visitors.

The scene is now brought closer to home and starts to convey loneliness as well as the physical isolation already laid out in the first two lines. The poet has been alone for some time and despairs of seeing anybody.

4. 蓬门今始为君开

But now my guest has just opened my battered old gate

The mood now changes dramatically, as often happens in poems of this style, a guest has come to see him, he is already at the gate. It is not a description of a static scene. His house is in a poor state of repair.

5. 盘餐市远无兼味

As the market is so far away, I have little worth eating

He needs to be able offer his guest a meal, but he does not have any decent food in the house. 餐 sūn is an archaic character for something like supper. The literal translation seems to be saying that the food is not worth tasting twice, there is no direct English phrase meaning quite the same. It does sound like a bit of an excuse as well as genuine poverty.

6. 樽酒家贫只旧醅

I have only some rough old homemade wine

Like numerous poets down the centuries, his thoughts now turn to drink. The poet's poverty is stressed again.

7. 肯与邻翁相对饮

Even so, I’ll welcome my guest and my elderly neighbor

His guilt at being so poor and having nothing much to offer is offset by the need for company, he asks his next door neighbor to come along too.

8. 隔篱呼取尽馀杯

I’ll call to him from my garden hedge, together we’ll finish off the wine

So the scene is set for a friendly chat while drinking, quite a transformation from the initial scene of desolation and loneliness. My medium sized dictionary does not have 馀 yú it means remainder. We are left thinking he's about to have a break from being alone and it could turn out to be quite an enjoyable time.

Putting it all together there is a strong impression of solitude, poverty and longing for company. Not bad for a mere 56 characters written over 1,200 years ago.

Direction of writing

It is worth noting that many Chinese poems are not written in the western traditional order: left to right in lines running from top to bottom. When poems were written/painted on scrolls of paper or strips of bamboo the poem was written top to bottom starting at the right and moving left as the scroll is opened out. This is the layout you see of poems on paintings. A great traditional painting will often have a poem written on it, this is not seen as defacement, the poem compliments the picture and the painting the poem.

篱

呼

取

尽

馀

杯

与

邻

翁

相

对

饮

酒

家

贫

只

旧

醅

餐

市

远

无

兼

味

门

今

始

为

君

开

径

不

曾

缘

客

扫

见

群

鸥

日

日

来

南

舍

北

皆

春

水

至

崔

明

府

相

过

Traditional characters

One of the most radical reforms made by the People's Republic in the 1960s were changes to the written language. Many characters have a simplified form with fewer brush strokes to make the language easier to read and write. The older forms are still used in Taiwan, Singapore and overseas Chinese communities. Anything more than fifty years old will be written using the older form of the characters. The changed characters are highlighted in brown in this final version. So the poem in a form close to Du Fu's original would have looked something like:

籬

呼

取

盡

餘

杯

與

鄰

翁

相

對

飲

酒

家

貧

隻

舊

醅

餐

市

遠

無

兼

味

門

今

始

為

君

開

徑

不

曾

緣

客

掃

見

群

鷗

日

日

來

南

舍

北

皆

春

水

至

崔

明

府

相

過