Nature symbolism in Chinese art

This group of symbols cover a wide variety of items with some sort of connection to nature. The Chinese Daoist strand of philosophy has always sought a harmonious and respectful relationship with nature rather than exploitation. We have separate sections on other natural subjects: animals, flowers & fruit as well as birds. Here we cover elements, minerals and natural patterns, here is the full list:

Amber Beard Children Cinnabar Cloud Dew Earth Fire Gall bladder Hair Heart Ice Jade Lacquer Meander Moon Mountain Numbers Pearl Rain Seasons Stone Sun Swastika Tai Ji Thunder Wave WineAmber 琥珀 hǔ pò

Chinese Amber, which is solidified pine resin, is most commonly found in Yunnan province. Its orange color has led to an association with tigers. There is an ancient belief that the spirit of a tiger goes back into the earth on its death to become amber. Therefore Amber has been used in TCM to give the properties of tiger to medicines. Amulets, beads and small bowls have been made from amber over the centuries. A bright red form - blood amber (血珀 xuè pò) - is considered particularly potent and has been used as an aphrodisiac. From very early times the Chinese knew amber was tree resin as they noted that sometimes insects were preserved inside it.

Beard 胡子 hú zi

Although long bushy beards are a common sight at the Opera, many Chinese men struggle to grow anything more than a thin, wispy beard. With the Confucian doctrine of reverence for elders a beard represents wisdom and scholarship. On stage and in pictures a beard symbolizes strength and supernatural power. However a red or purple beard is considered demonic because of from Buddhist representations and this stimulated Chinese apprehension to early European traders when they arrived sporting ginger hair and beards.

Children 孩子 hái zi

The wish for children is a very common motif in paintings, embroidery and porcelain. However, it must be admitted that traditionally the wish is for boys not girls. This apparent misogynistic attitude has to be explained. In the traditional village context a daughter would soon enough leave to marry someone in another village and would then have very little contact with her birth family (often only at New Year). On the other hand a boy would remain in the family home and have a strong Confucian duty to look after his parents into their old age. Scholarly or mercantile activity was restricted to men and so a family's dream of riches and continuity could only come about through bearing sons.

In ancient times children's hair was shaved off, leaving a boy with a central tuft over the forehead and a girl with two tufts over the ears.

Hé-hé èr xiān 和合二仙- the Heavenly twins are two boys carrying a box and a lotus to symbolize a wish for peace ‘hé’ 和 (box) and harmony 荷 hé (lotus). A picture may be divided in two, each part having a mother and son, one side has the son holding a lotus flower on the other the son rides a qilin, both symbolize a wish for a son. A picture with children surrounded by peaches and pomegranates symbolizes the wish for many sons.

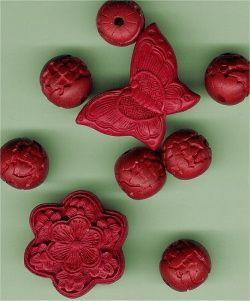

Cinnabar 丹砂 dān shā

Cinnabar is an orange-red mineral of mercury (mercuric sulfide). It has been associated with alchemy and magic in both China and Europe from the earliest times. This is because when heated it gives off hydrogen sulfide and produces a shiny, liquid metal - mercury - as if by magic. In China this transformation suggested properties connected to immortality, so some Emperors may have been poisoned by taking cinnabar elixirs (as most mercuric compounds are poisonous). The Elixir of the Immortals 仙丹 xiān dān was also said to contain cinnabar. It has been found as a red decoration on pottery dating back to the Yangshao culture (around 4,000BCE). Large amounts of cinnabar were used to produced for the rivers and lakes in Emperor Qin Shihuangdi's tomb near Xi'an. Many European alchemists believed all metals were made up of a mixture of cinnabar and sulfur. The English name comes from the Persian name Zinjifrah ‘dragon’s blood’. In Daoist belief there is a cinnabar zone just below the navel that is a key location in meditation.

The rich orange-red color of cinnabar was used to make the vermillion ink which was reserved for the sole use of the Emperor. Cinnabar provided the coloration of the red wax used for making the ‘chop’ (seal) marks on almost all old documents and paintings. When added to lacquer it makes the characteristic red color for intricate lacquer-work which is similar to the color of the bark of Cinnamon and Cassia trees.

Cloud 云 yún

Clouds are considered lucky and so feature heavily in Chinese pictures and symbolism. This is most likely down to the obvious connection that clouds bring the much needed rain to water the crops. It also sounds the same as 运 yùn ‘luck, fortune, fate’.

Dragons are often shown playing in the clouds because dragons are the masters of water and rain. A picture of bats flying among clouds is a wish for good fortune. The simplified motif form for a cloud looks like the shape of the 灵芝 líng zhī fungus (elixir of immortality). Clouds of five colors represent the five blessings of life. Clouds are considered the union of yin and yang because they are a fusion of the elements of water and air, sky and earth. From this idea clouds can symbolize making love as the union of male and female.

Dew 露 lù

As dew comes down from the sky to earth it symbolizes the benevolent rule of the Emperor, who as the ‘Son of Heaven’ was the link to the skies. Because a morning dew is such a fleeting affair it can symbolize a brief romance.

Earth 土 tǔ

Ancient Chinese thought that the Earth was a flat square and the Heavens above were round. Heaven and Earth were considered the two great divisions, earth is yin and heaven is yang. In combination with another character for earth 地 dì 天地 tiān dì ‘heaven and earth’ represents the whole universe. The second hexagram in the Yi Jingis made of all yin lines 坤 kūn and represents earth. Earth is one of the Feng Shui elements and one of the eight trigrams. The ancient cycle of 60 numbers is made up of twelve earthly branches (地支 dì zhī) combined with the ten heavenly stems (天干 tiān gàn).

Fire 火 huǒ

Although fire is chiefly seen as one of the five elements of nature it also has a symbolic meaning. It forms one parts of the Imperial insignia where it represents the Emperor's burning zeal to govern the people wisely. Fierce and active Buddhist deities are shown surrounded by flames.

Traditionally Chinese homes in the north did not have an open fire but a ‘kang’ as a form of heated seat and bed. All fires for winter heating were put out before the Qing Ming spring festival. The active meaning of fire may come from its closeness in sound to 活 huó ‘active, living’. Fire is considered a powerful agent to remove evil spirits. Fires at the New Year festival attract the good gods and scare away the bad ones. The ritual burning of ghost money and other offerings sends them to the spirit world. Some consider Fuxi was the deity who brought fire to mankind, but others say it was the Yellow Emperor.

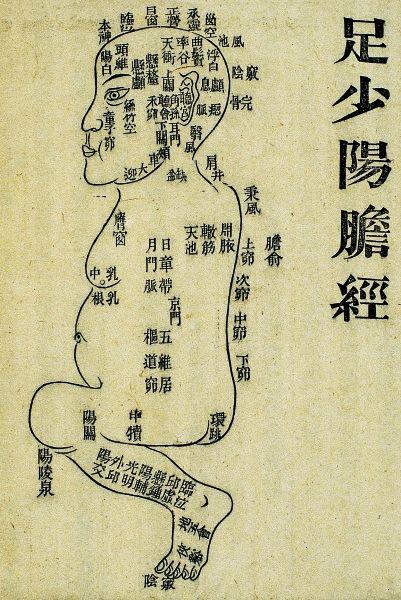

Gall bladder 胆 dǎn

In traditional medicine the gall bladder was thought to control a person’s temperament. The gall bladder produces bile to help digest food and it was thought that it expanded when people became angry. The gall bladder of violent criminals was considered to be a very potent medicine. It is one of the eight treasures of Buddha.

Hair 毛 máo

People's hair (头发 tóu fà is almost universally black in China. Although some youngsters bleach it to turn it orange/red and are so called ‘carrot tops’, it is generally straight but in southern china it can be naturally wavy. During the Manchu (Qing) dynasty men had to wear their hair as a pleated single, long ‘queue’ 辫子 biàn zi with forehead shaved to show subservience to the Manchus.

When fertilizer for crops was at a premium, hair was used as a valuable addition to manure; barbers used to collect and sell all the hair trimmings.

Traditionally, boys had their hair shaved to leave a single, central tuft while girls’ hair was shaved to leave two tufts one over each ear.

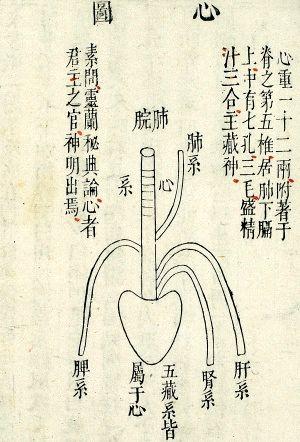

Heart 心 xīn

The heart is the source of emotions and held to be the seat of the intellect as well. It is one of the five main body parts and is represented in the system of five elements with fire. Many characters associated with emotions include the heart radical to give the hint that they represent strong feelings such as 怒火 nù huǒ ‘rage’, 怕 pà ‘fear’, 情 qíng ‘lust’ and 忿 fèn ‘anger’.

Ice 冰 bīng

Ice forms the boundary between air (yang) and water (yin), from this it symbolizes the match-maker (冰人 bīng rén) who forms the male-female partnership (a true 'ice-breaker' !). Ice symbolizes purity and winter. There is a design made from the pattern of cracked ice that is used in lattice window and porcelain designs. Ice also alludes to the story of Wang Xiang ➚ who was so devoted to his parents that he used his own body heat to melt ice so he could catch carp to feed his evil step-mother.

Jade 玉 yù

Jade is such an important precious stone in China that we have a whole section dedicated to it. It is valued above gold and symbolizes immortality. The Queen Mother of West has a jade pond 瑶池 yáo chí and holds a feast there for the immortals. The Jade Emperor is the supreme god in popular Daoist tradition.

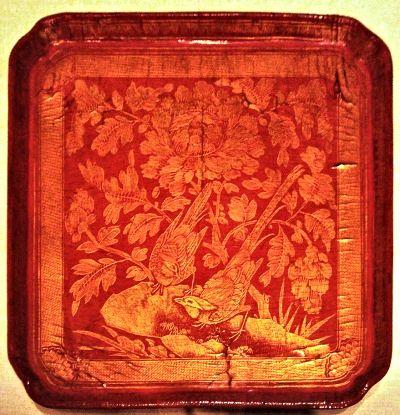

Lacquer 漆 qī

Lacquer is made from either the sap of the Lacquer tree Toxicodendron vernicifluum ➚ or the sticky secretions of the ‘lac’ insect Kerria lacca ➚. This latter ‘lac’ form is less common and is produced by deliberately infesting trees with the scale insects and then the heavily coated wood is harvested. Lacquer's origin is clear from the composition of the character as it contains both ‘liquid’ and ‘tree’. A lacquer tree is at its best at 14-15 years old. The solid resin is dissolved in turpentine and water and is applied in many, many thin layers to wood or paper to make a waterproof, antibacterial, durable surface that withstands moderate heat. A secret ingredient in the manufacture, is from a crab, as an enzyme from crustaceans prevent the lacquer from crystallizing. The best quality lacquer has a hundred layers and can take years to produce as each layer has to completely dry before the next is applied. It dates back at least 3,300 years in China. Whole dinner services were made from lacquer for the very rich. Other objects include chairs, screens, shoes and all kinds of boxes.

It can be dyed with various colors but red (traditionally from cinnabar) is the most common. It was used extensively on the decoration of coffins for senior officials. Lacquer work became very popular late in China under the reign of Qing Emperor Qianlong after which it became a specialty of the Japanese.

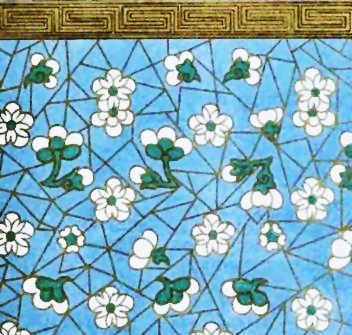

Meander 廻纹 huí wén

The meander pattern is a very common decorative edge on all types of object: lattice window frames, embroidery, lacquer-work, carpets and porcelain. The repeated linked meander pattern dates back thousands of years. It is usually made of nested squares but can also be of spirals and curves. Huí 回 means ‘return’ so there is symbolism of cycles and rebirth. Some consider that the meander pattern evolved out of the cloud and thunder pattern 云雷纹 yún léi wén and that it is related to the swastika pattern.

Moon 月 yuè

The moon is chiefly associated with yin in contrast to the sun which is yang. From this assignment everything ‘yin’ is also considered to be associated with the moon: female, Empress, cool and darkness. Pearls are considered to have come from the moon. The Chinese lunar calendar follows the cycles of the moon not the sun, please see our Chinese calendar section for full details. It is at the Autumn Moon Festival that the moon has its strongest influence. At this festival round, sweet moon-cakes are made and consumed with gusto.

The Chinese see the figure of a hare in the moon - not a man in the moon - the hare (or rabbit) is said to be perpetually making the elixir of immortality at the base of a cinnamon tree. The moon is also associated with the three legged toad and it is the abode of the goddess of the moon Chang-Er. Chinese Lunar space missions are named Chang'e after her and the lunar rovers are named Hutu ‘Jade Rabbit’ after the hare/rabbit association.

Han Emperor Wudi is said to have built lavish ponds so he could go and converse with the reflection of the moon.

An eclipse of the moon was said to be caused by the Heavenly dog star 天狗星 tiān gǒu xīng attacking it and temple bells were rung to drive it away. The Heavenly Archer Houyi would also be called upon to save the moon from the eclipse. The moon was much beloved by the poets and 李白 Li Bai is said to have drowned trying to embrace the reflection of the moon in the waters of the Yangzi. In a picture it is shown as a pinkish disk among clouds with curling waves to suggest its control over the tides.

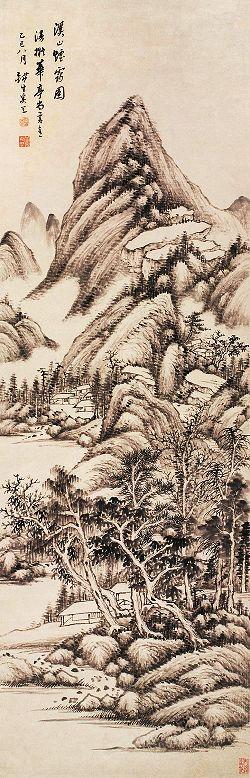

Mountain 山 shān

Many mountains in China are sacred, some to Daoists, some to Buddhists and others to both. In folk religion each mountain has its own deity associated with it. The pictogram character for mountain 山 shān has three towering peaks. ‘Mountains and sea’ represent the whole world 山海 shān hǎi. Mountains are the yang element in the landscape and as such connect to the governing yang element in China - the Emperor. Landslides and earthquakes were considered a strong portent that the Emperor's reign was in trouble. Mountain is one of the eight trigrams in Feng Shui and Yi Jing.

There are five sacred Daoist mountains each with its own element, color and direction association: Taishan, Shandong (East, element wood and color green); Hengshan, Hunan (South, element fire and color red); Songshan, Henan (Center, element earth and color yellow); Huashan, Shaanxi (West, element metal and color white) and Hengshan, Shanxi (North, element water and color black). Of these Taishan is considered the most important and stones from the mountain were often placed in towns across China as a lucky charm. Emei shan in Sichuan is sacred to Buddhists along with other faiths. The Kunlun mountains in the west (Qinghai) appear in many legends, they are the source of jade and the reputed home of the Queen Mother of the West. Chinese people climb mountains following the tradition of Emperors as a form of pilgrimage, the routes to the top can be thronged with people. The climb physically and symbolically brings you closer to the heavens. Mountains are thought to bring about the union of yin and yang to produce the much needed rain.

There is a famous tale of the ‘Old Man and the Mountain’ where an old man became so annoyed with a long detour to get to the other side of a mountain that he set about digging a way right through it. When a scholar pointed out the folly that such an old man should contemplate such endless toil; the old man replied that his sons and then their descendents would continue the task until it was completed. Mao Zedong used this tale as a parable for achieving the unthinkable by ceaseless toil but in the original story it was the Supreme God Shangdi who took pity on the Old Man and set his immortal minions to cut a way through the mountain.

Numbers 秘数 mì shǔ

Numbers play a major role in symbolism in China. Each number has many associations, for a full survey please see our numbers section.

In summary, four is the most unlucky and eight the luckiest but nine is the most powerful as it was associated with strong yang and the Emperor. Five is important because there are five elemental essences and associated with each element is a whole series of concepts in fives: color, musical notes, body organs, poisons, sacred mountains, blessings and compass directions. Eight plays an important part in the Yi Jing system as there are eight trigrams. Odd numbers are considered yang and male while even numbers are yin and female.

Each dynasty had a governing number which would decide many things - for example the size of the official's hats. An ancient counting system combined the twelve earthly branches and ten heavenly stems to form the sequence of sixty numbers used for counting days and years. Adecimal system was instituted at a very early date for all kinds of measurement.

The importance of numbers is very evident in the design of the Temple of Heaven, Beijing where almost everything comes in groups which have an underlying meaning. As nine is the Imperial number, this number predominates, with circles of nine stones expanding out by 9 until a count of 81 (9x9) stones are reached.

Pearl 珠 zhū

Freshwater pearls have been found in Chinese rivers from ancient times. The shiny translucent quality has long been associated with the moon. Legends consider pearls to originate from the moon which is sometimes known as 夜明珠 yè míng zhūthe ‘night shining pearl’. A pearl was once placed in the mouth of the deceased. Dragons are often shown chasing a pearl because of the legend that the phases of the moon are due to a dragon eating it. The pearl can also represent wisdom and so the dragon may be seeking enlightenment. As the pearl lies hidden inside the unprepossessing dark shell of a mussel, it also symbolizes hidden beauty or talent. It is one of the eight jewels of Buddhism and in this form it may be surrounded with flames to denote its magical powers.

Rain 雨 yǔ

The absence of rain spelled death to our ancestors, so the wish for life giving rain is a very common theme. One of the earliest recorded consultations using oracle bones was the question ‘will it rain?’. Many minor deities and gods could be appealed to in order to grant a wish for rain. Dragons as the controllers of all waters were the most powerful creatures. As rain falls from heaven (yang) to earth (yin) it is seen as the fruit of their union. Traditionally stones that were permanently wet or dry were associated with the wish for the rain to stop or start respectively.

A rainbow 彩虹 cǎi hóng symbolizes this marriage of yin and yang, and so love making. In ancient times the rainbow was shown as a two headed dragon. It represents making love but in an adulterous rather than in a marital context.

Seasons 岁时 suì shí

In ancient times the year was split into two parts: Spring and Autumn and this is the reason that the early part of the Zhou dynasty is called ‘Spring and Autumn Period’ as it referred to the annual records for the whole year. The two seasons were then each split into two to make the familiar four seasons. For one brief period a fifth season was added to fit in with the five-fold categorization of all things under the theory of elements; the extra season was inserted between summer and autumn. Chinese seasons were linked to the lunar calendar and because New Year is late January or early February it explains why early blossom such as plum is considered a flower of winter rather than spring. The four seasons are symbolized by flowers and these feature in Mahjong sets: winter – plum blossom; spring – peony; summer – lotus or orchid and autumn – chrysanthemum.

Stone 石 shí

Stones represent permanence and stability so it is not surprising that they symbolize longevity. A picture showing a rocky promontory over sea is often an allusion to the Isles of the Blessed, home to the immortals in the eastern ocean.

The character for stone is represented by a picture of a square stone falling off a cliff. From ancient times special stones, perhaps because of their shape, were considered sacred and received sacrifices for life-giving rain. Stones placed in front of buildings blocked the path of evil spirits, sometimes these stones originated from the sacred mountain Taishan and some have the inscription 石敢挡 shí gǎn dǎng ‘stone obstructs’. Perhaps because of this ancient belief many official buildings have stone lions in front of them (lion 狮 shī is a homophone for 石 shí). Stone figures line the important Spirit Way to the burial sites of eminent people.

The Chinese love for appreciating exotic shapes is most evident in gardens where heavily pitted rocks (often limestone) play an important part in the design. A scholar would have a rock (怪石 guài shí) ‘strange stone’ on their desk of a pitted, strange and complex form to act as a source of contemplation. The rock should be graceful, slim and elegant in shape.

Sun 日 rì

The sun, as might be expected, plays an important part in Chinese culture. It is the epitome of ‘yang’ (and in this regard is also called 太阳 tài yang) representing: light, heat, vitality, spring and east (where the sun rises). It also stand for the Emperor and so a solar eclipse would signify that the Empress (the moon) is too powerful, obscuring the Emperor's light. A picture of the sun and a phoenix together represents the Emperor and Empress and so expresses the wish for a happy marriage.

Another tradition has it that during a solar eclipse a celestial dog attacks the sun and needs to be scared off to restore the light. So temples would mark an eclipse with the ringing of bells. Traditionally a three-legged raven (or toad or cockerel) is said to live in the sun. There is the legend of the divine archer Houyi shooting down nine of the ten suns that threatened to burn up the Earth. Even in recent years Mao Zedong was compared to the sun, Mao badges were round to represent ‘The red sun in our hearts’ and the Chinese patriotic song is called ‘the East is red, the sun ascends’.

The sun's movement along the ecliptic divides the year into 24 solar terms (jieqi) which mark out the course of the agricultural or 岁 suì calendar.

Swastika 卐 wàn

The swastika is a Buddhist good luck symbol. Because Nazi Germany used it as their emblem its image has been severely tainted even though the European usage developed independently a long time afterwards. The swastika is an ancient symbol that came to China from India where it is the monogram of Vishnu and Shiva, it means ‘so be it’ in Sanskrit. It is said to symbolize the motion of blood in Buddha's heart. In China it is more associated with a wish for long life rather than good luck, it represents the endless turning of the wheel of life through multiple reincarnations. It is equally propitious in its mirror image 卍 form. It frequently occurs in the borders of decorative artwork and in particular wooden lattice window designs. Its four-fold symmetry made it an early representation for 方 fāng ‘square’.

In China it is also represented by 万 wàn which means 10,000 or more vaguely ‘countless, numerous, myriad, infinite’; making it appropriate as a symbol for plenty, multiplicity and immortality.

Tai Ji 太极 tàijí

The notion of yin and yang (click for full description) swirling and enclosing each other was promoted by the Neo-Confucianist Zhu Xi (1130-1200). There is a belief that at birth the placenta is marked by the 'S' motif of the taiji. The taiji is a universal emblem of the duality of all things and the absence of absolutes - yin can not exist without a little yang and vice-versa. It also suggests the creation of all things from the union of two opposites. It is in the form of a dynamic swirl to indicate yin will change to yang and then back to yin again in a never ending cycle. The Chinese characters 太极 mean literally ‘supreme ultimate’. However in popular usage it is mostly associated with the Tai Chi martial art.

It is a common talisman, particularly when surrounded by the eight trigrams 八卦 bā guà to keep evil at bay.

Thunder 雷 léi

Ancient superstitions about thunder and lightning go back thousands of years. Throughout the world, thunder was regarded as a sign of the wrath of the gods. The character for thunder is made up of ‘rain’ over ‘field’ which symbolizes the importance of storms to water the crops. The character for lightning is 电 diàn, a simplified representation of the old form 電, which is rain over a streak of lightning. Lightning is used in lots of characters concerning electricity for example 电视 diàn shì ‘television’; 电脑 diàn nǎo ‘computer’ and 电话 diàn huà ‘telephone’. The god of thunder is portrayed beating mighty drums with bat-like wings and red hair. His chariot is drawn by the spirits of the dead. Thunder is significant in Buddhism as lightning symbolizes Buddha's doctrine and is therefore its chief weapon against evil.

Wave 波浪 bō làng

The wave design is a common emblem in pictures and on the hem of garments. Water in regular waves represents the sea. The tide 潮 cháo is made up of waves sounds the same as 朝 cháo which means ‘Imperial court’ and so waves may symbolize a wish for a job in the Imperial service. A picture of a large and small fish 鱼 yú near the coast represents a wish for many (裕 yù) children to achieve high office.

Wine 酒浆 jiǔ jiāng

Up until modern times ‘Chinese wine’ was a distilled spirit from fermented sorghum or rice, much stronger than wine and not made from grapes and strictly speaking an ‘ale’. Grape wine 葡萄酒 pú tao jiǔ was not considered particularly palatable. It is only been in recent years that grape-vines have been cultivated and quality wine produced in China.

The character 酒 jiǔ shows a picture of an amphora shaped vessel for distilling together with the water radical. Wine in Chinese sounds just the same as 久 jiǔ ‘long duration’ and this makes alcohol an appropriate gift to wish someone a long life and may symbolize this wish in decoration.

Shaoxing, Zhejiang and Maotai (Moutai ), Guizhou are noted centers for traditional alcohol production. Drink was very much a social activity and carried out in moderation, often in the form of a series of toasts at meals. Although being tipsy was considered OK, drunkenness was a severe loss of face and was rarely seen. Alcohol was never a part of religious ritual as it is in Christianity.