Writing Chinese characters

There are a number of conventional strokes used to write, or more accurately paint, a Chinese character - because the characters are traditionally drawn with a brush rather than written with a pen and the pressure of the brush is as important as the motion. Many Chinese people spend considerable time throughout their lives perfecting their technique. In the past, hand-writing in the west was considered a good guide to character, this is still true in China. Some Chinese still make a living from working as a calligrapher. A good piece of calligraphy is a treasured artwork, indeed, many paintings have fine calligraphy written on them. At Chinese New Year there are many fairs that sell hand-written good luck posters to hang in the home.

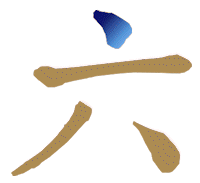

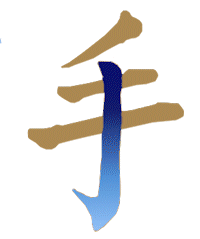

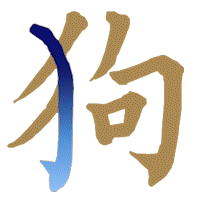

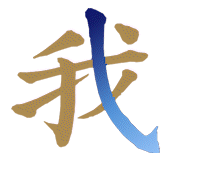

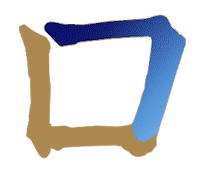

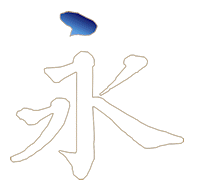

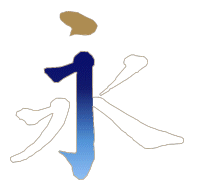

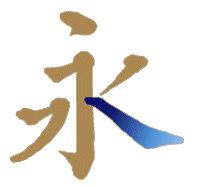

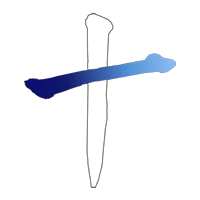

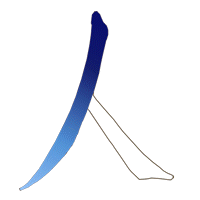

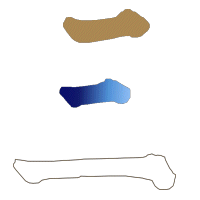

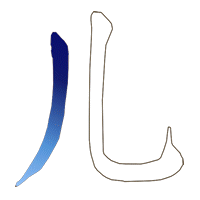

In the example diagrams for drawing characters we have put the main stroke in question in blue grading from the initial point of contact with the paper (dark blue) to where the brush leaves the paper (light blue). The other strokes that are needed to complete the character are shown in brown.

These examples are for just one of the many script styles used for writing characters; this is the standard official script. There are also flowing scripts more like western hand-writing that use curved strokes in which the brush rarely leaves the paper.

The simplest stroke is the 横 héng stroke. It is a horizontal line with the brush pushed down slightly at either end so it is somewhat like a 'bone'. Appropriately, the character for one (1) uses a single heng stroke. In Chinese this is 一 yī, one of only a few characters made with a single stroke.

Just as easy is the 竖 shù stroke. It is a vertical line with the brush pushed down slightly to start and lifted off at the end. Combining this with the héng stroke produces the character for ten (10) which is 十 shí. The horizontal stroke is drawn first followed by the vertical shu one. It is interesting that the Roman numeral for 10 is X, which is a rotated version of the same form. They both probably evolved from counting off in groups of ten with the cross stroke representing the completion of the group.

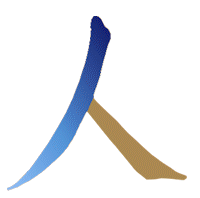

There are two types of diagonal strokes 撇 piě and 捺 nà. The piě stroke always starts at the top right and angles down to bottom left as the brush leaves the paper. One of many characters that include the pie stroke is the character for person which is 人 rén. The pie stroke is drawn first followed by a na stroke linking to it.

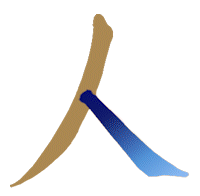

The 捺 nà diagonal stroke always starts at the top left and angles down to bottom right as the brush leaves the paper. Together with the pie stroke it makes up the character 人 rén for person. The na stroke is started within the previous pie stroke lifting off as it is drawn.

Another simple stroke is just a dot or 点 diǎn in Chinese. This is not quite a simple down and up motion, in this case the brush is dragged slightly to the right and lifted. There are a number of different types of dot stroke. Continuing with the numbers, here is the character for six (6) which is 六 liù. Above the heng stroke there is a dian or dot. The dot is drawn first followed by the heng horizontal line. In some characters the dot is drawn last.

The character for I is 我 wǒ in mandarin Chinese. It consists of the radical for hand (手 shǒu) on the left combined with spear (戈 gē) on the right. The 剔 tí stroke is the last part of the shǒu radical part to be written. It is an upwards and right darting movement to give it a pointed end.

Appropriately we use the character for write which is 写 xiě in mandarin Chinese to show the first composite stroke that is made in one movement. The heng gou 横钩 is a horizontal stroke héng with a hook gōu on the end pointing downwards by lifting the brush off to the left. In this case the vertical stroke is drawn first and then the hook stroke; together they form the ‘roof’ radical. Underneath is the pictograph of a bird, originally this was specifically a magpie which is a bird well known for collecting bright objects.

Just as the heng stroke can be adapted to heng gou, so shu can be modified by adding a hook at the end to form shu gou 竖钩. So the downwards shu stroke is terminated with a flick to the left to form the hook. One of many characters that use this stroke is 手 shǒu meaning hand. It is a representation of the lines that go over the palm of a hand. The other strokes are drawn first in order top to bottom; the final shugou stroke completes the character. This character is the radical in the 我 wǒ example above. Most radicals have a meaning when used on their own.

The hook can be added to the curved wan stroke to form a wan gou 弯钩 stroke. The character 狗 gǒu for dog has this as its first part. The wangou starts top left and curves round to vertical and then ends in a hook. The second part of the character is 句 jù means sentence as well as being a rough phonetic; taken together the character suggests barking. You will find the dog as a radical in a whole series of animal related characters such as lion, cat, wolf and the related adjectives mad and fierce. Of historical and cultural interest is the fact that dog was often used derogatively about the barbarian people living outside China.

The 我 wǒ character for I, me contains both a ti stroke and a xie gou 斜钩 stroke. It has the radical for hand shǒu on the left combined with spear gē on the right. The xie gou stroke is the first part of the gē character to be drawn. It starts at the top and is then angled down and then right with a hook at the end. The brush is lifted off quickly to make the hook while still moving right.

The ping stroke is more horizontal than the xie stroke and can be combined with a hook to make a ping gou 平钩 stroke. One of the most frequent characters containing a ping gou is the 心 xīn heart character. It has three dots, the leftmost one is drawn first then the ping gou stroke and finally the two dian ‘dot’ strokes on the right. The heart radical is quite common, and adds the idea of ‘emotion’ to a character. Characters for anger, longing, hearing and thinking all contain the heart radical. The pinggou starts at the top straight down and then curves right with a hook at the end. Some people call this stroke 卧钩 wò gōu.

Sometimes a box is painted with individual strokes around the edges, quite often two sides are painted as a single stroke with a sharp turn. The sharp turn is indicated by zhé in the name of the stroke. The character 医 yī for cure, heal has the element shī (quiver of arrows, miss) in an enclosure. The shu zhe 竖折 stroke is the last stroke drawn. It is often the case that the sealing stroke is the last one made - in order to accommodate the variable size of the elements already drawn inside the enclosure. See later section on stroke order. This stroke requires good brush handling technique to make a sharp clear turn - if not too careful it can end up as a curve. The brush has to momentarily pause at the change of direction. It is effectively a shu stroke followed by a heng stroke in one action.

The most obvious box shaped Chinese character is that for mouth 口 kǒu. You might think it should be made as a single stroke but this is not the case. Calligraphy avoids difficult upwards strokes, they are predominantly downward and rightward. The hengzhe 横折 stroke is made with a horizontal rightward stroke then a pause at the turn and then the downwards shu part. The kǒu character has a shu stroke on the left, followed by the hengzhe stroke to the top and right. The character is then completed by a sealing heng stroke along the bottom, so there are a total of three strokes. The mouth or ‘opening’ character is widely used in characters relating to speech or eating.

The previous strokes can be combined together in a variety of ways, only a few examples are given to give you a flavor. A sequence of shu, wan and gou gives a downward curve with a hook on the end. A widely used character with the shu wan gou 竖弯钩 stroke is the Chinese character for 也 yě also. The stroke is drawn downwards and then curving right finishing with an upwards flick to create a small hook. The yě character forms part of the personal pronoun he or she 他 tā has the radical for person (rén) to the left.

Another combination of strokes is pie dian 撇点. A slanting stroke from top right turns to leave a point. It forms part of the common character 女 nǚ for woman which is often used as a radical. As a component it gives the female gender to many other characters. Its use often betrays historical negative images of women, so it is a component of jealous and anger but on a more positive side it is also found in good and peace. The piedian stroke is made first followed by the left slanting stroke and finally a heng stroke through the middle.

The final example of a combined series of strokes is shu zhe zhe gou 竖折折钩. From the name you can guess it starts with a shu downward stroke followed by two sharp turns and a vertical hook. The ancient pictogram of a horse is brought to life with a few simple strokes in the character 马 mǎ. A heng zhe stroke is made first representing the head and mane of the horse. The shu zhe zhe gou stroke is then drawn completing the body down to the tail. Finally a single heng stroke for the legs but in the traditional form of this character (still used in Taiwan and elsewhere) the individual legs were drawn as four dots (馬). It is an ancient character which is widely used as a component in characters related to riding and travel.

Finally let's bring this all together with a step by step example of building up a complete character with all its individual strokes. The character chosen is 永 yǒng meaning everlasting or perpetual. It has eight of the fundamental strokes, and so it is often used in calligraphy practice - 永字八法 yǒng zì bā fǎ the ‘Eight principles of yong ➚’. Students can spend weeks just perfecting the writing of this character.

The first component is the ‘dot’ dian 点 stroke at the top. This follows the normal top to bottom rule for the order of drawing strokes.

The first component is the ‘dot’ dian 点 stroke at the top. This follows the normal top to bottom rule for the order of drawing strokes. Secondly there is a heng zhe gou 横折钩 stroke starting at the left and turning downwards ending in a hook to the left.

Secondly there is a heng zhe gou 横折钩 stroke starting at the left and turning downwards ending in a hook to the left. Next following the general left to right rule a heng zhe pie 横折撇 stroke. It starts rightwards and turns round quickly and off to the left. It should just touch the previous stroke.

Next following the general left to right rule a heng zhe pie 横折撇 stroke. It starts rightwards and turns round quickly and off to the left. It should just touch the previous stroke. This is followed by a diagonal downwards pie 撇 stroke trailing off as it just touches the center.

This is followed by a diagonal downwards pie 撇 stroke trailing off as it just touches the center. A final na stroke 捺 completes the character starting from the center, painting down before lifting off to the right.

A final na stroke 捺 completes the character starting from the center, painting down before lifting off to the right.See also

Writing Chinese characters: BBC Language guide ➚

Chinese characters on Yellow Bridge ➚

Order of strokes in Chinese characters

Here is a rough guide to the order of drawing Chinese characters. Strokes should be drawn in a particular order as this makes the completed character neater. In addition following the order helps avoid the possibility of smudging strokes. An important reason to learn the make-up of characters is that you need to count the number of strokes in order to look it up in a Chinese dictionary. These rules have exceptions, as all good rules have; in some cases you just have to learn the unique order for a particular character. In the examples we show the current stroke in blue (fading at the end of the stroke), strokes already drawn are shown in brown and the strokes yet to be drawn are shown in outline.

1. Across then Down

It is generally easier to draw horizontal strokes and these are drawn first. They often form the top of a character and so give it an initial form. This is the number 10 十 shí that has already seen as an example of the shu stroke.

2. Left falling then right falling

If the character has both pie (left diagonal) and na (right diagonal) strokes then the pie stroke is drawn first. The character for person 人 rén already seen above is an example of this ordering.

3. Top to bottom

Characters are drawn from top to bottom as much as possible, this avoids possible smudging. The number 3 三 sān has three horizontal strokes painted in top to bottom order.

4. Left to right

It is easier for a right-handed writer to move rightwards when holding a pen or brush. The character for son; child 儿 ér is an example of this. It has only two strokes, the left one is drawn and then the right.

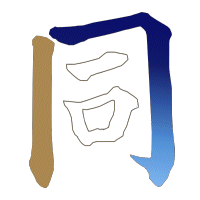

5. Outside to inside

To make sure there is enough space for the complete character it is best to do the outer box first and then the inner elements. The character for like; together 同 tóng has an enclosed area for the two elements inside it. The highlighted stroke is a hengzhegou stroke forming the top and right of the box.

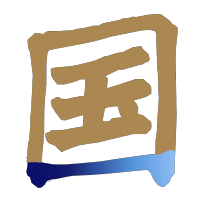

6. Complete last

The sealing stroke that completes an enclosing box is drawn last. This allows for some accommodation of the size of the inner elements. It is usually a horizontal stroke at the bottom of the character. Here is the character for country 国 guó. Inside the box is the character for jade 玉 yù.

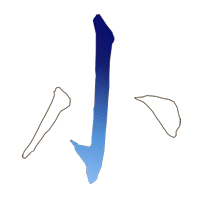

7. Middle first

If the character has a central, middle stroke that bisects the character this is done before the left and right parts either side. This gives a better balanced symmetry to the character. One of the simplest symmetric characters is the one for small 小 xiǎo, it has a vertical stroke dividing the two parts.

8. Dots last

In some characters the small dot (dian) strokes are added last. A common character in Chinese is the possessive article 的 de where the dot is drawn last of all. This is not a general rule, in some cases a dot is drawn first.

Don't forget that there are exceptions to these general rules; for these characters you just have to remember the order of strokes for that particular character.