Assorted symbols in Chinese art and history

Many of the elements that are used in Chinese art do not fall conveniently into any one neat category. This assortment of art motifs and symbols covers all sorts of traditions and customs from China's rich cultural heritage. For other lists on animals, birds, nature, flowers, fruit click on the list above. This section does not include the pantheon of gods and heroes from China's history, we have a separate guide to these important Chinese deities. Here is a list of all the assorted items in this group:

Amulet Ancestral tablet Ax Ball Bell Boat Book Bow Box Bridge Broom Brush Canopy Coin Eight treasures Endless knot Fan Filial piety Flute Ghost Gong Good luck gods Halberd Hat Heaven Hell Immortals Imperial Insignia Isles of the Blessed Laozi Longevity Luohan Lute Mirror Mouth organ Pagoda Pan Gu Pavilion Ru Yi Saddle Scroll Shoe Sword Taotie Tripod Umbrella VaseAmulet 护身符 hù shēn fú

Amulets since ancient days have been worn in China to bring good luck. The spell on a typical amulet is written in a very old ‘Spirit script’ (pre-Han dynasty) to ward off evil. The script could only be read by the spirits and proved a lucrative sideline for the Daoist priests who were the only people who could write it. An amulet was often made of jade and may also have baguo trigrams inscribed.

The earliest amulets were in the form of rings, half-moon pendants and 璧 bì cylindrical disks. Talismans could also be in the form of tiger's claws, a silver lock, a small mirror, jade or yellow paper with the spells inscribed.

Ancestral tablet 祖 zǔ

The ancestral tablet is an essential part of Ancestor Veneration, the most ancient Chinese tradition. The paternal line was inscribed with names and dates of birth on the tablet that measured roughly 12 inches [30 cms] by 3 inches [8 cms]. The tablet takes central place in the shrine, on a small table with candles, incense sticks, pictures and offerings within the home, usually along the north wall. The tablet is usually made of lacquered wood. Wives names are inscribed on it alongside their husbands.

This tradition had a powerful influence on the preference for boys, as a woman could only be memorialized as a wife on her husband's family's tablet and only a man could officiate at the ritual of veneration. More distant relatives are noted on a separate paper scroll. Part of the ancient ceremony was to pour chicken blood over the tablet to give sustenance to the spirits locked inside it. The number of ancestral tablets on display are a proud advertisement of the longevity and stability of the family line. It also served as a proof of identity. Should someone behave really badly their name would be struck off the tablet, and this was considered a great punishment in itself. At the Spring Festival the whole extended family would gather and pay homage to the tablets. At the Qing Ming festival, the graves and ancestral tablets are the main focus of ceremony.

Ax 斧 fǔ

An ax (fu 斧) wrapped in a red cloth is the traditional gift for a bride. It symbolizes the end of virginity. Fu is a homophone for good fortune and happiness 福 so an ax symbolizes best wishes. The shaft of an ax is made of wood but an ax is needed to cut down a tree so it is regarded as the ‘agent’ needed for the harvesting of timber; and so an ax represents the marriage match-maker. An ax (axe) is also one of the twelve symbols of the emperor's power (symbolizing justice) and also the symbol of many Buddhist deities fighting evil forces.

Ball 球 qiú

A large cloth ball is often seen in Chinese Opera. A long time ago at the Mid Autumn moon festival a maiden would throw a red ball and the suitor who caught it would become her husband. It was often fixed onto the bridal carriage to symbolize the wish for babies to come. Dragons play with an embroidered ball at the Lantern festival where it probably represents the pearl of wisdom or the moon. At the entrance to temples there are often two stone lions, one of which has a ball under its left paw representing the ‘egg’ of a lion cub.

Bell 钟 zhōng

The bell is one of the Chinese characters that is easy to remember as ‘zhong’ sounds rather like the sound of a bell. The modern form of the character is made up of the metal radical combined with 中 zhōng as the phonetic for ‘middle’. Appropriately it also means ‘o’clock’ from the sounding of bells from a town's bell tower to mark the passage of the day.

A stone chime 磬 qìng is an ancient musical instrument rather like a bell, it was an ‘L’ shaped stone suspended by a string and struck with a stick. Originally the stones were made of jade. The chime is important in symbolism because 卿 qīng means ‘high ranking official’ and 庆 qìng ‘celebrate’. Sometimes two qings are shown placed together to form a rectangle to represent ‘doubling’ the wish for an official appointment. A bell and a ruyi together is a charm to keep away evil.

Huge bells date back thousands of years in China. The first Qin Emperor is said to have melted his defeated armies bronze weapons down to make bells. Bells were played as musical instruments from early days, carefully tuned to form a continuous note progression. Large bells are hung from large wooden bell frames arranged by size and note. They are sounded by hitting with a wooden staff. An early set from the Warring States period consists of 65 bells ranging from 5 feet [2 meters] to just 8 inches [20 cms]. In later dynasties they became associated with religious temples and a bell is sounded at a Buddhist temple at midnight. Wind bells were fixed to roofs to make a melodic sound in the breeze. Hand bells are also used in China and a monk would often rattle small bells to beg for alms. In a painting a bell may wish luck as 中 zhòng (fourth tone) means ‘succeed or win’.

Boat 船 chuán

Seeing a scholar in a boat in a painting makes for a nice, tranquil scene but there is a further level of meaning that may not be obvious. Boat 船 chuán sounds the same as 传 chuán ‘to pass on; generation’ and so gives the wish for the whole family to be prosperous over many generations

Book 书 shū

China has the longest history for printing books in the world. Early books were made from thin strips of bamboo, wrapped up like a scroll. Because the Chinese script has so many characters it was a long and painstaking process to hand carve the wooden blocks so text can be printed. For this reason books needed a long and large circulation to be economically viable; this may be why such emphasis was put on the Five Classics of literature. Budding scholars had to learn key passages by heart in order to pass the Imperial examinations. Imperial projects assembled ‘all’ knowledge into huge thousand volume encyclopedias. When European travelers such as Marco Polo reached China they were amazed by the abundance and low price of books.

The first Qin Emperor is famous for the ‘burning of the books’ which was used to impose his new unified script over the whole of China. All books written in other scripts or histories or those opposing the Legalist philosophy were ordered to be burnt. Paradoxically this resulted in many books being preserved as their owners hid them away to be uncovered centuries later. Ancient classics were considered powerful talismans against evil, and they were treated with respect - the book's paper was not re-used but ritually burnt when the books were no longer usable.

In a painting, books have the obvious meaning of scholarship. Books and red apricots together is another wish for examination success (A 尚书 shàng shū was an eminent court official). A baby boy when he reached 100 days old would be given a tray of different objects, if he grasped a book then he was sure to grow up to be a scholar.

Bow 弓 gōng

The character for bow is a pictograph of the compound bow that was used in China from ancient times. There is a Chinese legend (similar to that of Odysseus ➚) that there is a mighty bow that only the chosen one has the strength to torsion. The Divine Archer Hou Yi 后羿 was the most adept archer and is associated with early legends; he shot down nine of the original ten suns (or ravens) so that the Earth would not be too hot. His wife Chang 'e is goddess of the Moon.

The archer is seen as fighting against evil and shooting arrows into the sky is a fairly subtle euphemism for a wish for many sons.

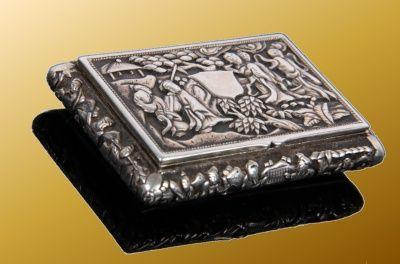

Box 盒 hé

The character for a small box sounds the same as 和 hé which can mean ‘peace; harmony’ and so a box portrayed in a picture symbolizes peaceful wishes. This wish is amplified by the presence of lotus leaves and a scepter. The expensive and lavishly decorated lacquer boxes of China have been treasured as great works of art for centuries. Hé-hé èr xiān 和合二仙 - the Heavenly twins of ‘Harmony and Union’ are shown as two boys one carrying a box (or sometimes a bowl) and the other a lotus flower.

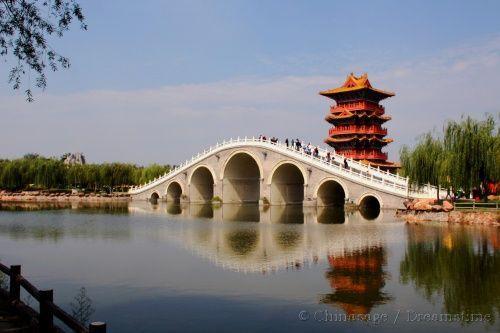

Bridge 桥梁 qiáo liáng

A bridge is a physical and symbolical link between two different pieces of land. In a painting it often symbolizes a journey, a transformation or the transition between life and death.

On the River Wei near the ancient capital of Chang'an, Shaanxi is the ‘Blue Bridge’ where people took leave of their loved ones before embarking on a long journey. Another famous tale is of Zhi Nu and Niu Lang who were separated in the heavens only to be united once a year over a bridge of magpies. Many romantic stories are told of people meeting on or near bridges.

Broom 扫 sào

The broom is used for sweeping up, and it has come to be associated with various superstitions, a broom should not be placed in the room of someone who is very ill (sweeping away life), or in a gaming room (sweeping away luck) . It can also symbolize wisdom and insight as it sweeps away ignorance and worry. A broom is used to sweep the house ritually clean just before the New Year Festival in readiness for a fresh start to the new year but must not be used during the festival itself.

The broom is associated with the Daoist Shide 拾得 the eccentric side-kick of the legendary Han Shan 寒山 a well known poet. Shide is represented as a smiling figure holding a broom.

扫晴娘 Sǎo qíng niáng is the goddess of fair weather and is shown using a broom to sweep away the clouds.

Brush 笔 bǐ

A writing brush is one of a scholar's four treasures. The shaft is traditionally made of bamboo and the brush of animal hair. A calligrapher is still an esteemed professional in China and quality of calligraphy is regarded as a good judge of character. As well as symbolizing scholarship directly a 笔 bǐ can represent certainty as 俾 bǐ means ‘to cause’. So combining a brush with an ingot (锭 dìng) and a ruyi together gives the wish 必锭如意 Bì dìng rú yì ‘You will be sure to have all you desire’.

Canopy 盖 gài

One ancient view of the world in China was that the earth was a chariot and the heavens a canopy above it. The use of cloth canopies as a sunshade goes back to the Han dynasty. The Queen Mother of the West is often shown under a canopy, but it is best known as one of the eight Buddhist symbols and represents the lung of the Buddha.

Coin 钱 qián

Ancient Chinese coins were round with a square central hole. These shapes reflect the ancient shapes of earth (square) and heaven (round). Coins were often used as lucky charms but they had a symbolic meaning too. For a complete history of coins in China please see our Chinese money section.

The central hole is called an eye 眼 yǎn. A particularly symbolic way to wish good fortune is to combine bats and coins (钱 qián). The bat symbolizes good fortune 褔 fú and together with the coins symbolizes ‘before your very eyes’ 福在眼前 fú zài yǎn qián. In some places a long time ago children wore a necklace of coins, one extra coin was added on each birthday. The homophone 迁 qiān means ‘promote, advance’ so money can symbolize a wish for advancement rather than wealth. A string of nine coins symbolizes continual happiness (as 九 jiǔ ‘nine’ sounds the same as 久 jiǔ ‘long time’). Coins were conveniently put onto strings by threading through the central hole, a string of 100 cash was considered a good luck present at New Year.

A money tree probably reflects the way that multiple bronze coins were cast in a mold at the same time. A popular Chinese Opera is called ‘Shaking the money tree’.

Silver ingots in the shape of a shoe or boat represent a much larger amount of money. They were called 'sychees' 细丝 xì sī and can weigh up to 100 ounces. They were also called 元宝 yuán bǎo and because 元 yuán means ‘first’ a picture of three silver shoes represent wish to come first in all three levels of the Imperial Examinations. Three coins on a string also symbolizes this wish 连三元 lián sān yuán passing all the examination grades.

Eight treasures 八宝 bā bǎo

Of all the numbers eight is the luckiest and so there are many sets of eight symbols to give a wish for good fortune. For all about the symbolism of numbers see our numbers section. The most important sets of eight are: the Eight Buddhist treasures, the Eight Daoist Immortals (each with their own treasure) and the Eight Trigrams of Yi Jing (I Ching).

Eight Buddhist Treasures (八吉祥 bā jí xiáng)

Many of these are important symbols in their own right and so have their own entry in this section. To make their Buddhist association clear they are often shown tied with a ribbon, they are:

Bell : frighten away demons.Canopy 盖 gài: for protection and power of spiritual truth.

Conch shell 螺 luó: signifies high rank, thought and the lungs of Buddha.

Endless Knot 盘长 pán cháng: signifies immortality, harmony and the guts of Buddha.

Lotus 荷花 hé huā: beauty, enlightenment and purity.

Fish 鱼 yú: a pair of fish signify harmony, abundance, marriage and freedom.

Banner or Umbrella 伞 sǎn: for spiritual authority and clarity.

Treasure Vase 罐 guàn: treasure and wealth, perpetual harmony and store of holy relics.

Wheel of law: 轮 lún: symbol for Buddha's teachings, eternity and the power to defeat delusions.

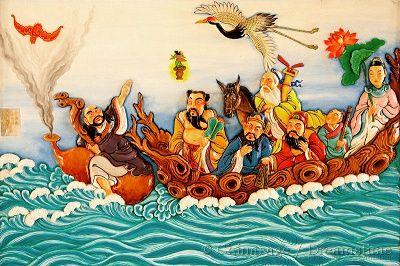

Eight Daoist Immortals (八仙 bā xiān)

We have a section describing each of these important Daoist deities, here we just list the symbols that are often used to refer to them symbolically.

Sword: emblem of Lu Dongbin, slayer of demonsFlute: emblem of Han Xiangzi, a musician

Castanets : emblem of Cao Guojiu, an actor

Fan: emblem of Zhong Liquan who also carries a peach of immortality

Lotus: emblem of He Xiangu, she represents self-sacrifice

Flower basket: emblem of Nan Caihe associated with flowers and nature

Gourd : emblem of Li Tieguai, the gourd contains a magic potion

Bamboo drum: emblem of Zhang Guolan, a great magician

Eight Precious things (八宝 bā bǎo)

These are items of value that have mainly symbolic meanings. Over the centuries different objects have made up the set :

Coins 双钱 shuāng qián: wealthRhinoceros horns (horn shaped drinking cups) 犀角 xī jiǎo : happiness

Artemesia leaf : good luck and healing

Lozenge 方胜 fāng shèng : an open frame (a form of head ornament) - victory

Pair of books : learning, casting of protective spells

Stone chime (磬 qìng) : good luck, successful career

Mirror : wards off evil, brings happiness

Dragon or Flaming Pearl (宝珠 bǎo zhū) : good fortune

Other treasures that may appear in the set of precious things include silk, ruyi, ivory and coral.

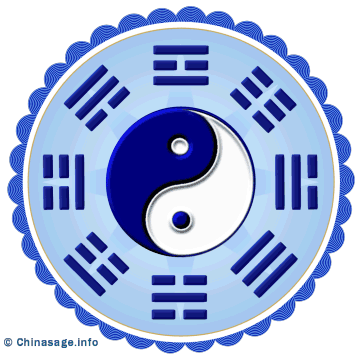

Eight Trigrams 八卦 bà guà

These form the basis of the Yi Ching/I Ching. Every possible combination of three broken and straight lines gives the eight trigrams. For a full description see our Yi Jing section.

兑 duì Lake: pleasure, satisfaction乾 qián Heaven: tireless, power

坎 kǎn Water: peril, difficulty

艮 gèn Mountain: rest, peace

震 zhèn Thunder: excitement, change

巽 xùn Wind: flexibility, penetration

离 lí Fire: brightness, elegance

坤 kūn Earth: yielding, fruitfulness

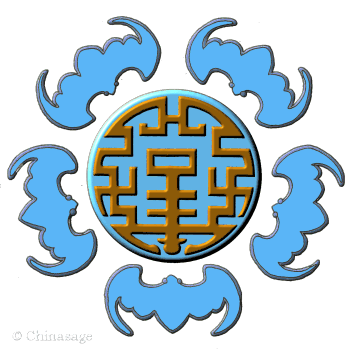

Endless knot 盘长 pán cháng

The endless knot is a common decoration in China. It was originally a Buddhist emblem from India and also used in Hinduism. It is used in embroidery, wooden lattice window designs and all sorts of other places. The most common form has nine crossings (nine being a strong yang number) and its endless cycle suggests immortality and the infinite wisdom of Buddha.

Fan 扇子 shàn zi

Originally the fan was not the decorated folded fan you associate with China today, they were original unfolded. The old ones came in all shapes and sizes and were made from feathers, silk, paper and palm leaves. The folded fan probably came from Korea in the 10th century, they are more convenient as they can be carried in the sleeve or in a case fastened to a belt. Folding fans may have ivory, horn or sandalwood frames with decoration often in mother of pearl, lacquer or tortoiseshell.

Over time it became traditional for men's fans to have far fewer ribs than women's - which could have over 30 ribs. Decency dictated that only women would be depicted on women’s fans. In elite circles fans were used with its own particular etiquette, and gestures had specific meanings ➚. This is still evident when fans are used as props in traditional opera.

A fan is the symbol of Zhongli Quan, one of the Eight Immortals. Fans may symbolize benevolence and good wishes as 善 shàn ‘good, virtuous’ sounds the same. It may also directly symbolize the well-to-do, particularly court officials. The decoration of the silk or paper surface of a fan reached high artistic perfection; typically one side would show a landscape and the other a piece of fine calligraphy.

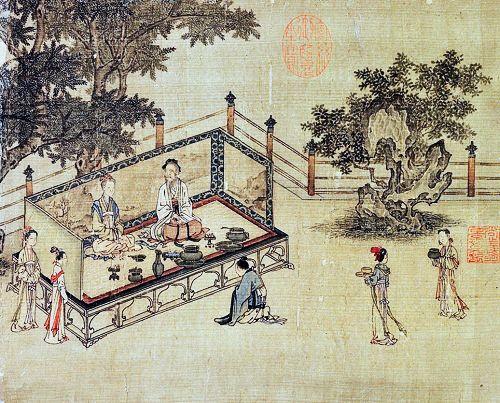

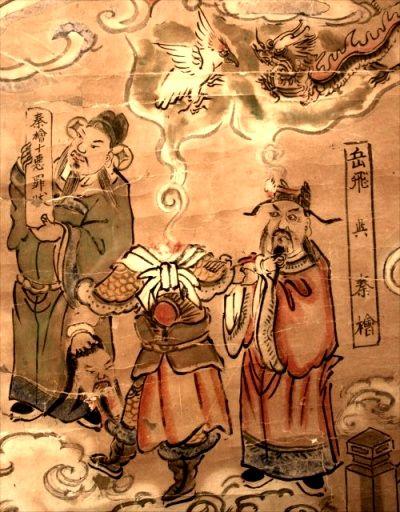

Filial piety 孝 xiào

Filial piety - the selfless service of parents is chief among the Confucian canon of virtues. Many examples of dedication to please parents have come down through the centuries. A well known classic is the ‘24 examples of Filial piety ➚’. It recounts examples of extreme dedication such as: sons going without food to ensure parents do not starve; Zhou Yanzi taking to a life disguised among a herd of deer so he could collect doe's milk to cure his father's illness and the tale of Huang Xiang who warmed his father's bed each night.

The Chinese went into a long period of mourning on a parent's death lasting several years. Many pictures and ceramic designs portray examples of filial piety such as oranges (to celebrate the tale of Lu ji ) and crows.

Flute 笛 dí

The transverse held flute is said to have come from Tibet two thousand years ago, it is considered a melancholic instrument and so can symbolize sadness. Traditionally it is a tube with eight holes, one to blow through and one with the reed leaving six to modulate the sound. The clear, shrill sound is thought to provide a connection with the spirit world and so in opera it often accompanies the apparition of a ghost.

The vertically held flute 箫 xiāo has an older heritage and this is usually played by women. Xiāo shī 箫师 who lived in the Tang dynasty was considered the master of flute playing. Both types of flute have the bamboo radical as part of the character emphasizing their manufacture from bamboo tubes.

Han Xiangzi 韩湘子 (and sometimes Lan Caihe) one of the Eight Immortals is usually shown holding a flute.

Ghost 鬼 guǐ

As in most countries a belief in ghosts was widespread in China. 'Guǐ' 鬼 denotes an malevolent creature, while friendly ghosts, particularly family ghosts, are called 'Shén' 神. ‘Hungry ghosts’ are aggrieved because they have been separated from their families and seek vengeance. Ghosts cast no shadow and appear as dark clouds, but they are short-sighted and lurk in dark corners. The seventh month of the Chinese calendar year is the ‘ghost’ month with a festival to mark its start and the Hungry Ghost festival at its middle. 洋鬼子 yáng guǐ zi ‘Ocean demons’ was a derogatory term for foreigners from Europe and America.

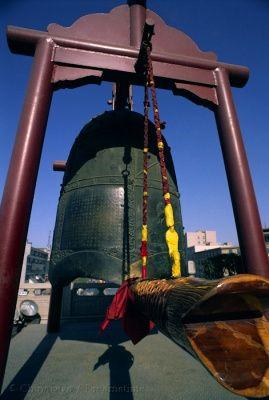

Gong 锣 luó

Gongs are commonly made of brass and cast into the familiar low conical shape. They come in a variety of sizes up to two feet wide and are suspended by string and hit with a wooden mallet. It is generally struck to announce something, traditionally this might be a solar eclipse (to scare away the monster eating the sun) or the arrival of a senior official. The Yùn luó 韵锣 has ten small gongs suspended in a frame and is often seen in traditional musical ensembles and operas.

Good luck gods 五福 wǔ fú

The number Five is heavily used in Chinese symbolism, usually indicating luck. The five gods of good luck are represented as officials dressed in red. The good fortune is also stressed by presence of bats (also called fú 蝠). Sometimes the symbolism works the other way where five bats represent the five gods.

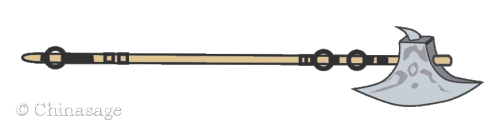

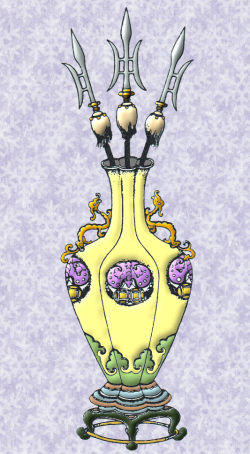

Halberd 戟 jǐ

The halberd or pole-ax is a type of spear that is sometimes used symbolically in paintings. This is because ji sounds the same as 机 jī ‘opportunity’ and 级 jí ‘grade; rank’ and so expresses the wish for luck particularly in examinations.

Combinations of halberds and other objects are common in designs, as there are three stages of examination, three halberds usually represent wish for success in all three grades. A halberd, stone chime and a vase make the wish 吉庆和平 jí qìng hé píng ‘peace and good fortune’.

Hat 冠 guān

A hat sounds the same in Chinese as an official 官 guān and so a hat represents the wish to become a well paid official. Each of the nine grades of official wore a hat with a different decoration so they could be easily distinguished. A boy wearing a hat siting on a dragon expresses the wish to be the top student.

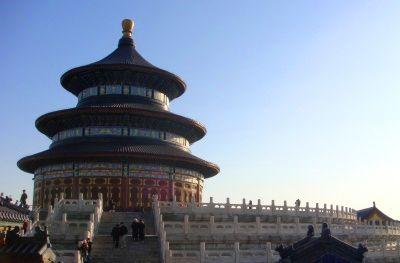

Heaven 天 tiān

Heaven (sky; day) is the pair to Earth, it represents yang (male) in contrast to earth yin (female). The Emperor as the ‘Son of Heaven’ acted as the sole conduit between Earth and Heaven. The stars in the sky are laid out, according to Chinese tradition, as an Imperial court with the Emperor at the Pole star. Good fortune is considered to fall down from the heavens. There is no belief in China of a Christian/Islamic heaven for the souls of the departed, instead the souls of the virtuous go to the Isles of the Blessed.

The Christian missionaries translated their god as 天主 tiān zhǔ while the Supreme Chinese god is Shangdi 上帝. ‘All below heaven’ 天下 Tiān xià was a term used for the whole civilized world and for a long time a name for the country of China.

Hell 地狱 dì yù

The Chinese hell is generally a less fearsome place than the Christian one. People are punished after death for their misdemeanors, but not for eternity so it is more like the Christian purgatory. Hell can be transliterated as ‘earth prison’ and is divided into ten sections with the first one being the place of initial judgment. Each section is then subdivided according to the particular sins to be punished and ruled by specific demons. The belief in an after-life is strong in China (see ghosts) and ‘hell’ probably came into China with Buddhism. It is the Buddhist tradition that has provided vivid portrayals of the horrors of hell.

Immortals 仙 xiān

Many of the Chinese Immortals are based on historical figures who, due to their great virtue, were given immortality; there are hundreds of them; often associated with a particular place. Some say they live in the Isles of the Blessed or with the Queen Mother of the West in the Kunlun mountains. Even living people may be termed 仙 xiān if they live a virtuous life or show great talent.

The Eight Immortals are the most widely shown group. Sometimes they are pictured greeting the god of longevity flying past on a crane. These are associated with the Daoist tradition; quite frequently just the eight distinctive insignia for each immortal is shown: gourd; fan; flower basket; bamboo tube; lotus; sword; flute and ruyi.

Imperial Insignia 十二章纹 shí èr zhāng wén

The Imperial insignia were displayed on robes and decorations at the Imperial palace. Some sources say there were nine insignia, but most have twelve (one for each lunar month). They date back at least four thousand years and are mentioned in the Classic text the 书经 Shū jīng ‘Book of Documents’. Only the Emperor could wear the full set of twelve, lower ranks of nobility could use only a few of them.

They are :

Upper garment

- Sun (日 rì) Symbol of yang, often with a three legged cockerel or raven at its center.

- Moon (月 yuè) Symbol of yin, may include the jade rabbit at its center.

- Three Stars (星辰 xīng chén) Part of the Big Dipper constellation and the seat of Divine Justice.

- Mountains (山 shān) Represents stable rule over the earth.

- Dragon (龙 lóng) A pair of five clawed imperial dragons representing Imperial power and control over all waters. Reminds the Emperor that he should inspire all to virtue.

- Pheasant (野鸡 yě jī) Pheasants represent all the birds, and the Empress (sometimes the phoenix is used instead). It is an example of the quieter virtues.

Lower garment

- Two vessels (宗彝 zōng yí) - represent loyalty, ancestor veneration and filial piety. One cup is decorated with a tiger (strength) the other with a monkey (cleverness).

- Water plants (藻 zǎo) - represent purity and water. Some such plants are considered as giving immortality.

- Grain (粉米 fěn mǐ) - represent food and fire, and is often in the form of millet. Reminds the emperor of his duty to feed the people.

- Fire (火 huǒ) - represent the Emperor's fervor to govern wisely as well as the element fire.

- Ax (黼 fǔ) - the head of an ax to represent decisiveness and punishment of evil.

- Fu (黻 fú) - two back to back bow symbols (亞 yǎ) represent the judgment between good and evil. Homophone with fu - good fortune.

Isles of the Blessed 瀛州 yíng zhōu

The Chinese have a legend of an island paradise out to the East - in the North China Sea - possibly relating to legends about Japan. The blessed live there for eternity. They are known by various names for this Eastern ‘Avalon ➚’ including 方丈 Fāng zhàng, 蓬莱 Péng lái and 瀛洲 Yíng zhōu.

The Qin Emperor Shihuangdi sent out Xú Fú 徐福 in 219BCE to search for the Islands of the Blessed in the hope that he would bring back an Elixir of Life to give him immortality. Xu is said to have seen the islands but was held back from getting close by strong easterly winds. The islands can only be reached by immortals and cranes.

Some say the herb of immortality grows here and that it is a type of water grass with long leaves. Zoysia pungens ➚ 芝 is one candidate plant. The herb is sometimes shown in the mouth of a deer or in the beak of a crane emphasizing the symbolism of immortality. It is reputed that only some deer and phoenixes are able to find it.

Others say the herb of immortality is actually a bracket fungus, possibly Ganoderma lucidum ➚ (灵芝 líng zhī) which grows widely on decaying trees. Unlike other fungi and wood Lingzhi remains solid indefinitely which may explain the association with immortality. Some similar species are bright red and it is often portrayed in works of art to represent a wish for long life. Many different types of mushroom are used in traditional medicine.

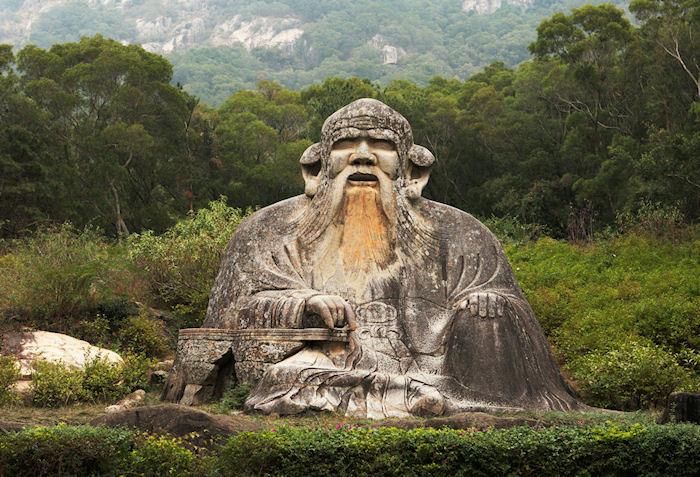

Laozi 老子 lǎo zǐ

Laozi, literally ‘old master’ is the legendary founder of Daoism. Please see a dedicated section on Laozi for his biography and more on Daoism. Laozi is a common subject for pictures and figurines and so deserves an entry under symbolism. He is always portrayed as a bearded old man with a bald head usually riding a water buffalo. He is easy to confuse with the god of longevity as he also symbolizes longevity as well as a revered religious figure.

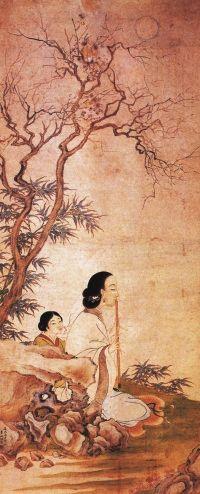

Longevity 寿星 shòu xīng

The God of Longevity is a very common art motif, often on silk gowns as an artistic form of the character for longevity 寿.

The God of Longevity is a tall old man with a bald, elongated head and white beard. He usually rides a deer and may hold other emblems of longevity including a peach, a crane, ruyi, mushrooms of immortality and a long knobbly wooden staff. He may be accompanied by a boy. Some say he lives at the South Pole (as 南极仙翁 Nán jí xiān wēng) where he tends a garden growing the Herb of Immortality. The other part of his name 星 xīng means ‘star’ and he is associated with the bright star Canopus in the Argo constellation.

He is one of a trinity of good fortune deities: Fu, Lou and Shou representing ,Good fortune Prosperity and Longevity.

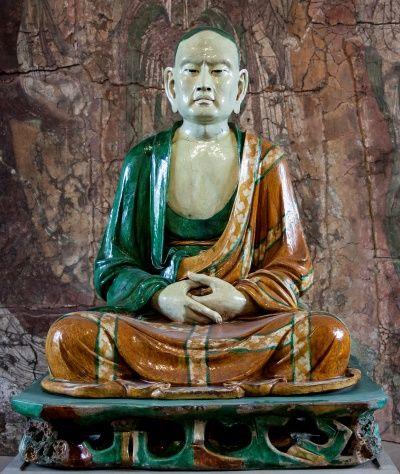

Luohan 罗汉 luó hàn

The eighteen Buddhist ‘arhats’ are called 十八罗汉 Shí bā luó hàn in Chinese and hold a similar place in Chinese affection as the Eight Daoist Immortals. Luohan means ‘destroyers of the enemy’ and these enemies in Buddhism are the passions. A luohan (or lohan) has dispensed with all the passions and so is free from reincarnation and reached nirvana ➚. Although eighteen are distinguished in illustrations temples often have up to 500 luohan.

Of the eighteen, sixteen are Indian in origin, only two are Chinese. Every luohan has a standard pose and is associated with particular animals and objects by which they can be identified.

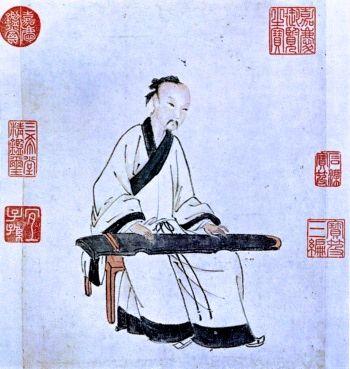

Lute 琴 qín

There are many different lute-like instruments in China. The qin 琴 qín short for 古琴 gǔ qín is one of the oldest and most appreciated type of zither. It has a long body, laid on a table with seven strings and is plucked with the fingernails. Originally, in the Han dynasty, it only had five strings.

Qin can also mean 禁 jìn ‘prohibit, forbid’ and one legend says the name comes from the ability of the instrument to soothe and so ‘prohibit’ violent passion.

A standard size for the instrument is 3 chǐ 尺 (feet) 6.6 cùn 寸 (inches) long to represent the 365.25 days in a year and 1.8 cùn 寸 (inches) thick (0.3 x 6)

A similarly ancient instrument is the 瑟 sè which generally has more strings. Most of the scholarly élite of China were expected to display some proficiency at music, and particularly on the guqin. It was one of the four accomplishments of scholars together with 象棋 xiàng qí chess; 书 shū literature and 画 huà painting, this makes a qin symbolically represent the wish to become a scholar.

The pipa 琵琶 pí pá is a widely seen form of lute similar to a mandolin. It came to China from Iran. It symbolizes good luck. The famous concubine Wang Zhaojun ➚ is often shown holding a large pipa, she was sent by Han Emperor Yuan as a peace trophy to the Xiongnu tribe. She is considered one of the chief paragons of beauty.

Mirror 镜 jìng

In ancient times mirrors were circular and made of bronze and they gave an imperfect reflection that soon tarnished. Around the center a decorated border was often fashioned. A bronze mirror 铜镜 tóng jìng sounds similar to 同谐 tóng xié ‘together in harmony’. Later on silver and gold were used to produce a clearer reflection. As in Europe the mirror is associated with magical properties 护心镜 hù xīn jìng; it makes spirits visible and so can be used to see the ‘hare in the moon’; it also keeps evil at bay. If people do not recognize themselves in a mirror it is a sign that death is near at hand. In Feng Shui the ba gua mirror has a central circular mirror surrounded by the eight trigrams and is used to control the flow of qi, and reflect bad qi away.

There is a legend that a mirror split in two can be used to monitor a loved one far away, if they are each given one half of it, and one proves unfaithful it will turn into a magpie and fly away. A mirror is considered lucky and if a man finds one, he will soon find a wife, it is therefore an appropriate gift for an unmarried man.

Mouth organ 笙 shēng

You may see the traditional musical instrument the ‘sheng’ or reed organ - an elaborate form of mouth organ - in art work. This is because it happens to sound the same as 升 shēng ‘to ascend’ so it represents a wish for promotion. The sheng typically has 17 bamboo pipes arranged in a ring and blown from a special mouth piece.

It has now fallen out of fashion and is only commonly seen among the mountain people of southern China.

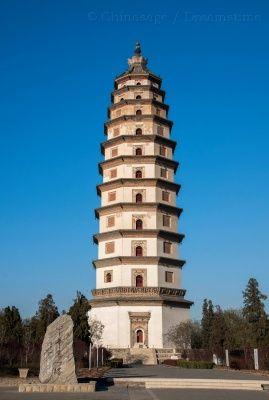

Pagoda 宝塔 bǎo tǎ

The pagoda is a frequent motif in Chinese paintings and on porcelain. It is described in our Chinese architecture section.

Some were built to house sacred Buddhist remains, but with the Chinese open attitude to religion they do not generally have a religious connotation when depicted in a picture. They can be octagonal or circular and usually of seven or nine levels (always an odd number). Sometimes they were built to counter poor Feng Shui in a location, and in a picture they serve a similar purpose, balancing the composition and giving a visual measure of distance.

Pan Gu 盘古 pángǔ

The legend of Pangu as the progenitor of all creation seems to have come late to China, probably from minority people of southern China, in ancient China there was no divine creator.

On the death of Pangu his body parts became the earth and all living things. Sometimes he is portrayed as hewing the Earth from rock and sometimes with the symbol of yin-yang, this is related to the Daoist doctrine that from the One came the Two (yin and yang) and from these all things.

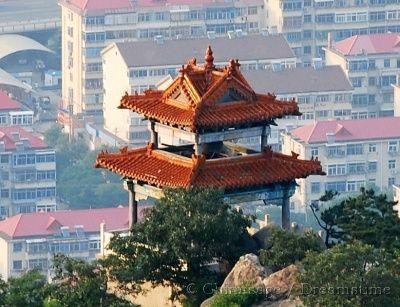

Pavilion 亭 tíng

Rather like the pagoda, the pavilion is a familiar motif in Chinese painting. They are usually of one or two levels and often located by lakes. Many villages had small pavilions to give protection to travelers from the elements, and as such were the scene of many amorous encounters. High ‘flying’ eaves decorate the roofs (see our architecture section for more on this). One popular motif is a round pavilion set high in mountains to represent the Isles of the Blessed.

Ru Yi 如意 rú yì

The decorative emblem ‘ruyi’ (a.k.a. joo-i WG) symbolizes a wish for success without any obstacles as it translates to 如意 rú yì ‘according to wishes’. The ruyi represents a ritual short sword and sword guard originally made of iron. It dates back at least two thousand years where one form may have been used as a back-scratcher. In the Qing dynasty it became an extremely popular symbolic object with ambassadors exchanging ruyis with the Emperor. The gift of a ruyi signifies good wishes for future prosperity. It is often used as a decorative motif in embroidery and wooden window lattices. Versions were held in the hand and raised to show respect for others. The head of the sword (the sword-guard seen end on) resembles a bat in shape which is another symbol for good fortune. This shape without the sword element is said to mimic the plant/mushroom (lingzhi) of longevity/immortality and the lotus and here it looks rather like a cloud with a tail. It may have come from the Buddhist tradition and came to symbolize wealth and power. It is also associated with the ceremonial scepter 珽 tǐng and the jade tablet 圭 guī.

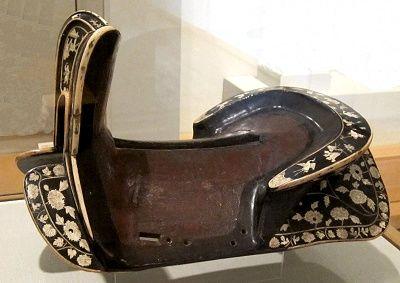

Saddle 鞍 ān

The horse saddle is sometimes used to symbolize peace as 安 ān ‘peace’ sounds the same. It was used in the marriage ceremony by being placed in the house so that the bride would step over the saddle symbolizing a wish for peace and harmony in married life.

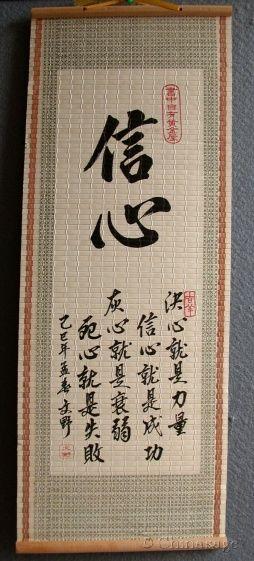

Scroll 卷 juàn

The Chinese have been writing and painting on scrolls for millenniums. The slow unraveling of a scroll has had a profound impact on Chinese art. Instead of seeing a scene all at once, a scroll painting is revealed progressively. This explains some of the finer points of composition of paintings. Writing too, is influenced by the scroll. Traditional writing is top to bottom; right to left as this is much more convenient when reading from a scroll, and so a poem on a scroll is not seen all at once it is revealed little by little.

Originally writing was on thin strips of bamboo before the invention of paper. A scroll has the advantage that it is easy to place a seal over the end when wrapped (made of clay or wax over one end) so that it can be certain that the contents have not been read by intermediaries. Scrolled poems or proverbs are often created as ornamental objects to be hung on walls.

Scrolls are traditionally associated with Buddhist scripture and these were the very first printed books in the world. As such they symbolize truth and enlightenment. They are often considered one of the Eight Precious Things.

Shoe 鞋 xié

As shoes come in pairs there is an implicit link to a wish for marital harmony. Silver ingots are made in the shape of a shoe (or boat) and so shoes commonly represent wealth. In some areas shoes were exchanged to express the wish to live in harmony. It also sounds the same as 协 xié ‘harmony’ to reinforce the message. In Cantonese xié is pronounced ‘hai’ and expresses the wish for a child. A shoe and a bronze mirror together symbolize wish for a long marriage as 同 tòng ‘together’ sounds similar to 铜 tóng ‘copper; bronze’.

The bound feet of women were called lotus feet and as ‘lian’ for lotus sounds the same as 连 lián for ‘continuous’ a picture of women's shoes may therefore represent a wish for ‘a succession of children’.

Sword 钢刀 gāng dāo

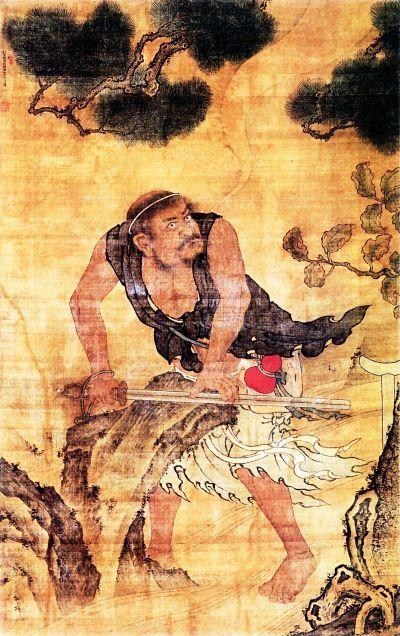

From ancient times fine swords were highly valued. Sword-smiths are known from 4,500 years ago, well before the Iron Age ➚. Symbolically a sword was used by heroes to overcome demons. One of the eight immortals (Lü Dongbin) 吕洞宾 is shown carrying a demon-slaying sword. Likewise 钟馗 Zhōng kuí is another hero brandishing a sword to destroy evil demons. Gān Jiàng 干將 and Mò Yé 莫邪 were a married couple of sword-smiths from the Warring States Period, who with great heroism fashioned a pair of powerful swords (one male; one female).

Taotie 饕餮 tāo tiè

The ancient design element of the ‘Taotie’ is commonly seen on the designs of Zhou and Shang dynasty vessels. It is a scary portrayal of the head of the ‘Beast of Greed’ and warns against the evils of avarice and sensuality. It was also depicted on the 照壁 zhào bì ‘shield wall’ blocking direct access into a house or yamen reminding an official and his visitors of the temptation of gluttony and avarice. It depicts a monster's face with two huge eyes and powerful jaws. Sometimes it has antlers and sometimes the head of a tiger. According to legend the monster was banished by Emperor Shun. It was used as the basis for a horde of evil monsters in the film The Great Wall (2016) ➚ starring Matt Damon.

Tripod 鼎 dǐng

Heavy ancient cooking vessels made of bronze called ‘ding’ are often seen outside temples and in museums. Many of them date back at least 4,500 years. They achieved symbolic importance because the possession of the nine tripods represented the Emperor's control over the nine regions of China. Each tripod was said to be engraved with a map of the region. If the tripods were lost then it was believed that this indicated that the mandate of heaven had been withdrawn and the dynasty would fall. The three feet represent the three Grand secretaries ruling China under the direction of the Emperor. They are now used primarily as good luck symbols.

Umbrella 伞 sǎn

The umbrella or parasol is a Chinese character which is clearly portrayed with the minimum of strokes. The old form has four people sheltering underneath it 傘. Traditionally it was made of bamboo sticks covered with waxed paper. Folding umbrellas have been known in China from two thousand years ago. Wenzhou in Zhejiang is famous for manufacturing umbrellas.

A ceremonial umbrella of red silk was presented to a respected administrator when he left office, it had the names of the donors emblazoned on it in gold. An umbrella is one of the eight sacred Buddhist emblems. It represents protection as it wards off rain and by extension evil spirits.

Vase 瓶 píng

Traditional vases in China tend to be of porcelain, bronze and not glass. They come in many different styles often designed to show off a particular type of flower. As 平 píng ‘peace’ sounds the same, the gift of a vase symbolizes a wish for peace. A rare and precious vase 宝瓶 bǎo píng sounds the same as 保平 bǎo píng ‘ensure peace’. A picture of a vase with flowers will add the wish for peace, so a vase containing the representative four seasonal flowers 四季 sì jì (plum, lotus, chrysanthemum, pine) gives a wish for peace throughout the whole year 四季平安 sì jì píng ān.

The vase is one of the eight precious Buddhist symbols and so appears frequently on Buddhist artwork. In this case it is not for flowers but an urn used to hold sacred relics.