Boxer Rebellion 1898-1901

The Boxer Rebellion 1898-1901 exemplifies the complexities of late Qing dynasty times. Although the Manchu rulers were seen as foreigners by the Han Chinese people, an explosion of 'anti-foreigner' sentiment spread through China at times directed as much against the 'foreign' Manchus as against europeans. In southern China the western foreigners had not been forgiven for siding with their Manchu overlords during the Taiping Rebellion.

The origin was as an anti-Manchu movement called the White Lotus sect ➚ which had Buddhist connections. The Boxers, known as Yi he tuan 义和拳 in China ‘Righteous and Harmonious Fists’ believed that their martial arts were proof even against bullets (they followed the Daoist 'Wushu' technique). An earlier uprising in the 18th century had been suppressed by the Qing, but in 1898 the Boxers arose again in Shandong and Hebei. In August 1898 a Yangzi River flood killed and dispossessed millions of people, this was followed in 1899 by drought. Such natural disasters were widely seen as the loss of the dynasty's Mandate of Heaven and made rebellion a legitimate action. Heavy taxation and unemployment due to a influx of cheap foreign imports gave them the support of ordinary working people. They followed the tradition of grassroots rebellions against a failing dynasty and wore lucky red uniforms. Shandong in particular suffered from rapid industrial development by foreign powers without regard for the local people and their customs. The Boxers first targeted Christian missionaries and their converts (often 'rice bowl Christians', lured to baptism to escape famine).

Siege of the Legations

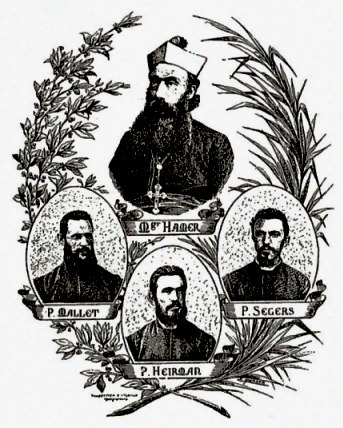

The Boxers were given semi-legal status by the Governor of Shandong when he was unable to quell the revolt, but deflected their anti-Qing sentiments towards the foreigners. Outlandish rumors had developed about the devilish acts of foreign missionaries. The missionaries sought out dying babies so they could at least be baptized before death; locals assumed that the babies were wanted for body parts, particularly the eyes. The singing at mission services gave credence to belief that wild orgies were taking place in churches. The foreign architecture of stone-built, tall churches were widely considered to be damaging to Feng Shui and the flow of the qi life force. It was alleged that the missions were deliberately spreading smallpox and that people were hypnotized into converting to Christianity. With all these wild tales and half-truths it was easy to stir up hatred. In all about 180 missionaries and 32,000 converted Chinese Christians were slaughtered by the Boxers . General Yuan Shikai was sent by Beijing to suppress the rebellion, and peace was restored in Shandong for a while but soon the rebellion spread into Hebei nearer to the capital Beijing, where once again the foreign missionaries bore the brunt.

The storm then hit the foreign legation quarter in Beijing. This was a small area close to the Forbidden City which held the embassies of nine foreign powers (Britain, America, Germany, France, Italy, Austro-Hungary, Russia, Japan and Italy) and was besieged for 55 days (A Hollywood film ‘55 days in Peking ➚’ [1963] portrays life at the time from the European perspective). On 11th June 1900 the Japanese Chancellor of the legation was murdered and on the 20th June the German foreign minister was shot dead. The legations banded together and built barricades. The reports of the situation reached Europe fueling a tremendous clamor to rescue them. A report claimed that all the hostages had been slaughtered and this turned the ‘rescue’ mission into one seeking ‘revenge’.

The foreign legation siege is given prominence but just as desperate were the French priests, converts and missionaries besieged in the French cathedral ➚ also in Beijing. Most of the many deaths at the cathedral were from starvation rather than violent death.

The Boxers also exacted revenge on any Chinese seen as collaborating with the foreigners. On June 16th 1900 a medicine shop in the hutong district of Dashilanr, Beijing was attacked. The Times of London reported:

“Adjoining buildings took fire, the flames spread to the bookseller’s street and the most interesting street in China, filled with priceless scrolls, manuscripts and printed books was gutted from end to end. Fire licked up house after house, and soon the conflagration was the most disastrous ever known in China, reducing to ashes the richest part of Peking, the pearl and jewel shops, the silk and fur, the satin and embroidery stores, the great curio shops, the gold and silver shops, the melting houses and nearly all that was of the highest value in the metropolis. Irreparable was the damage done.”

Imperial Support

Dowager Empress Cixi at first supported the Boxers, she proclaimed ‘The foreigners have been aggressive towards us, infringed on our territorial integrity, trampled our people under feet… The common people suffer greatly at their hands and everyone of them is vengeful’. On June 18th 1900 she commanded the Imperial troops to join the Boxers against the foreign legations in Beijing. She issued an edict that all foreigners should be killed, two brave reformist officials (Yuan Chang and Xu Jingcheng) modified the edict from ‘slay’ to ‘protect’ but their forgery was discovered and they were executed. On one day 45 missionaries (men, women and children) were slaughtered in Shanxi, Cixi commended this action for ridding the province of ‘a whole brood of foreign devils’.

On June 23rd the Hanlin Academy adjoining the British embassy was deliberately set alight and only with desperate measures were the legations saved from the flames. After fierce fighting the siege was lifted by an Allied force of 1,500 (more than half the foreign troops were killed), thereupon Cixi adopted a disguise and fled north from Beijing to Xi’an. The victors went on a spree of looting and raping in Beijing and imposed more onerous demands on China in the Allied Boxer Protocol ➚ with additional financial reparations imposed on China, the Qing dynasty officials who had supported the rebellion were commanded to be executed. Some foreign powers considered that China would cease to exist as a country and break into regions without central control, as that had recently happened in the case of Poland ➚. In July 1900 many Boxers were arrested and beheaded. Russia used the uprising as an excuse to pour 200,000 troops into Manchuria.

The extra-ordinary passion and fierce spirit of the Boxers (fighting with fists and knives against rifles) surprised the foreign powers who were poised to calve up China into areas of foreign control, expecting little resistance. The rebellion can therefore be seen to presage the end of Manchu rule and the resurgence of a spirit of Chinese nationalism. Mao Zedong certainly read much into the event, he wrote:

“Was it the Boxers organized by the Chinese people that went to stage rebellion in the Imperialist countries of Europe and America, and Imperialist Japan to commit murder and arson? Or was it the Imperialist countries that invaded our country to oppress and exploit the Chinese people?”