Chinese Steles 碑石 bēi shí

A stele is any sort of inscribed stone (for example gravestones). [The plural can be written as stelae or stelai as well as steles]. A stele is the general term used for inscribed stones all over the world. In China the inscription is called a 碑铭 bēi míng or 碑文 bēi wén.

Many Chinese steles were produced over the centuries as extremely durable copies of writing. The oldest known is the ‘Ten Stone Drums’ 十石鼓 Shí shí gǔ) in Shaanxi from the Spring and Autumn Period 2,500 years ago. Emperor Qin Shihuangdi of the following Qin dynasty erected steles in the new Qin unified script at several places including at Mount Taishan, Shandong.

Complete classic texts

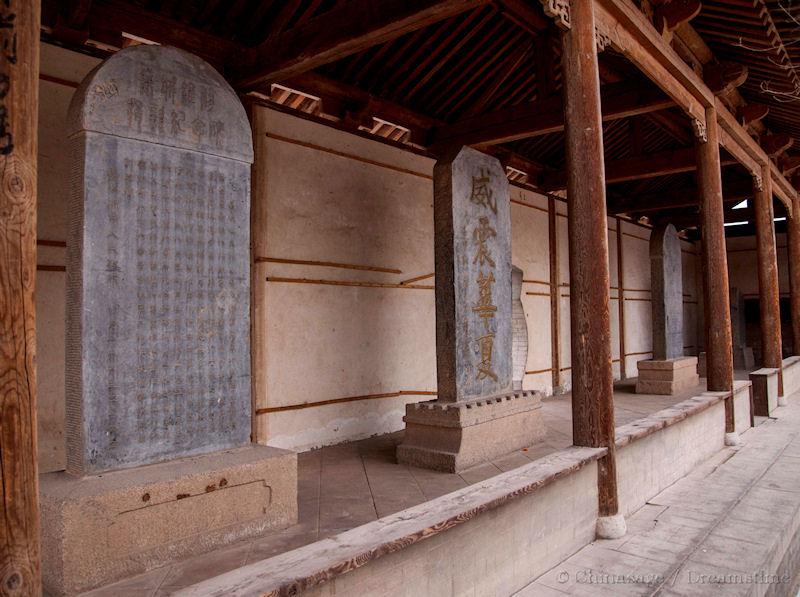

The complete text of the Chinese Classics was engraved into large numbers of stones on several occasions from the Han period (熹平石经 Xī píng shí jīng) onwards (175CE , 837, 1177 and 1793CE) so that scholars had access to these essential writings before books became widespread. The engravings made in 837 are still mainly intact as the ‘Forest of steles’ (碑林 bēi lín) at Xi'an. The museum has over 1,000 steles of which the classics only take up 114 steles (about 560,000 characters) and represent the most complete copy of the classics ever to have existed. Also at the Xi'an museum is the large ‘Classic of Filial Piety’ inscribing the calligraphy of Tang Emperor Xuanzong. In another hall there is an inscribed detailed map of Chang'an at the peak of its power and size during the Tang dynasty.

The most prestigious academic institution, the Hanlin Academy, Beijing collected many historic steles and many of these survived the burning down of the academy in 1900 and can still be seen in the Confucius Temple, Beijing. Here also is an inscribed list of all the top students of the Imperial Examinations over the centuries.

Not all steles were inscribed with text, a star map dating to 1193 is an example of a stele used as a diagram rather than writing. The map was engraved in 1247 and can still be seen at a Confucian temple at Suzhou. It names 1,565 individual stars and shows the path of the moon and sun through the constellations.

A great increase in the number of steles occurred when Buddhism reached China (c. 600CE) as many Buddhist scriptures were inscribed on steles in the Chinese style together with carved images.

Other religions created steles to proclaim scripture. One of the most famous was found at Chang'an in 1625. It was written in both Chinese and Syriac and documents the arrival of Nestorian Christianity into China. The monk Alopen arrived in 635 and the stele records the church's early history, it was then called the ‘Da Qin Luminous Religion’ (Da Qin was the term for the Byzantine Roman Empire).

Memorials

However the most common use of steles was for memorials (记碑 jì bēi) that document the life and achievements of the deceased. Empress Wu Zetian famously asked that her memorial stele should have no inscription as she said her accomplishments would speak for themselves. This, however, did not stop succeeding dynasties adding 13 inscriptions. Many memorial steles are flat blocks of stone set into the back of a carving of a bixi (a mythical tortoise-like creature).

Other steles commemorate historical events rather than people such as disasters that took place near where the stone is placed.

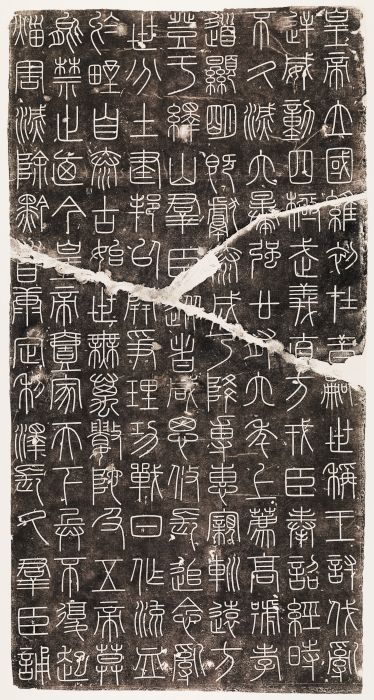

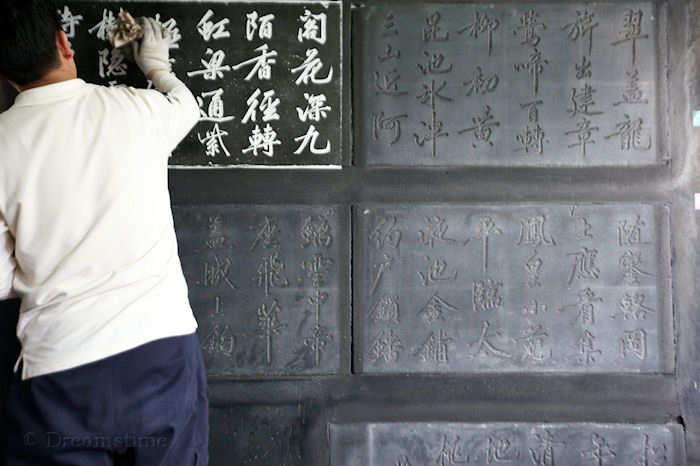

Another important use of steles was as artwork to permanently capture the style of renowned calligraphers. This tradition began in the Song dynasty. The intention was to allow students and scholars to not just read the inscription but take away a faithful copy of the style of calligraphy. This can be considered an early form of book printing. Students could then make an accurate copy; this was made by taking a rubbing - paper was placed on the stone and then rubbed with black wax or tamped with a bag of black ink.

Sacred mountains

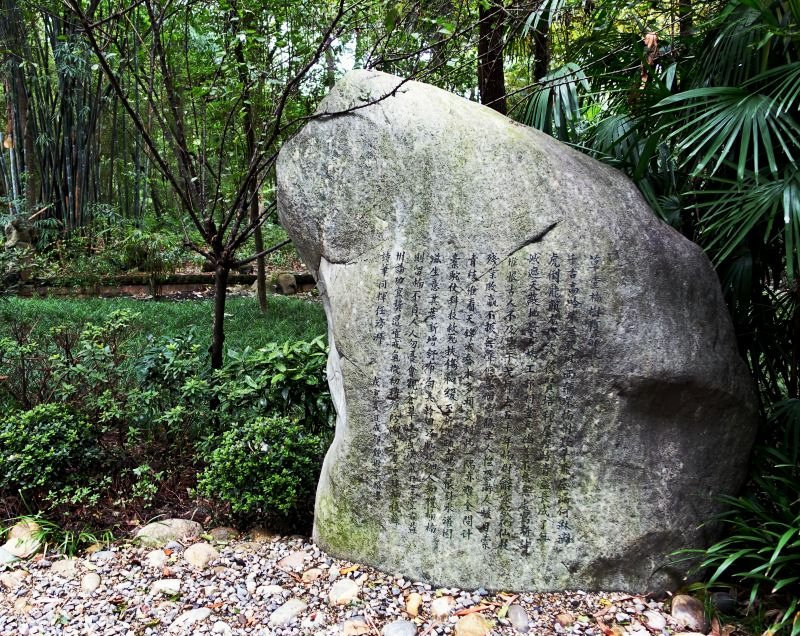

Stelae were also erected at famous scenic sites, particularly sacred mountains where they were inscribed with poems describing the poet’s admiration of the scenery.The Frenchman Victor Segalen ➚ [1878-1919] visited and copied the inscriptions on many steles in 1909-17. He published a book of poems entitled ‘Stèles ➚’ in 1914 drawing on Chinese poems from throughout Chinese history.

Here is an example poem from his collection, translated from the French by Billings and Bush.

To honor renowned Sages; to enumerate the Just; to repeat on all sides that such a man lived, and was noble, and his countenance virtuous,

All that is good. All that is not my concern: so many mouths discourse of that!

So many elegant brushes apply themselves to replicate formulae and forms

That the memorial tablets pair off like watchtowers along the Imperial Way, five thousand paces upon five thousand paces.