European and British contacts with China 1700-1800

Another page has looked at the few, early contacts between the UK and China leading up to 1700. As many still regard the first contact with China was with the Opium Wars (1842-60), it is important to lay bare the events that led up to it. The 18th century saw a substantial shift in attitudes towards China even though direct contact was limited.

Around 1700 there were two strands of contact: mercantile and intellectual. British traders were keen to dislodge the Portuguese, Spanish and Dutch from their very lucrative monopoly of trade with the East. The ‘conquest’ of India became Britain’s main focus with the mighty English East India Company (EIC) dominating the trade. Once India became a cash cow, bringing fortunes to the company and its employees, thoughts naturally turned to China. India had an ancient civilization that had fallen into decline; surely India's neighbor, China, would just as easily fall into Britain's lap?

Such was the merchant trader's perspective but at this time the general view of writers and intellectuals in the whole of Europe was one of admiration of China. It was considered to be an ancient and remarkable civilization, the epitome of wise government and makers of goods of great quality and beauty.

Trading with China

The traders who sailed the seas were there to make a profit. In 1557 Portugal had secured control of Macau leading to a stranglehold of the Guangzhou (Canton) trade. However near the end of the century, in 1684, the English East India Company did manage to establish their first factory (warehouse) at Guangzhou. As Portuguese foreign activities dwindled in the 17th century it was the Dutch who became the next to lead foreign trade . It was only after the Jesuit influence at the Imperial court was lost that Protestant nations, such as the Netherlands were permitted to trade in China.

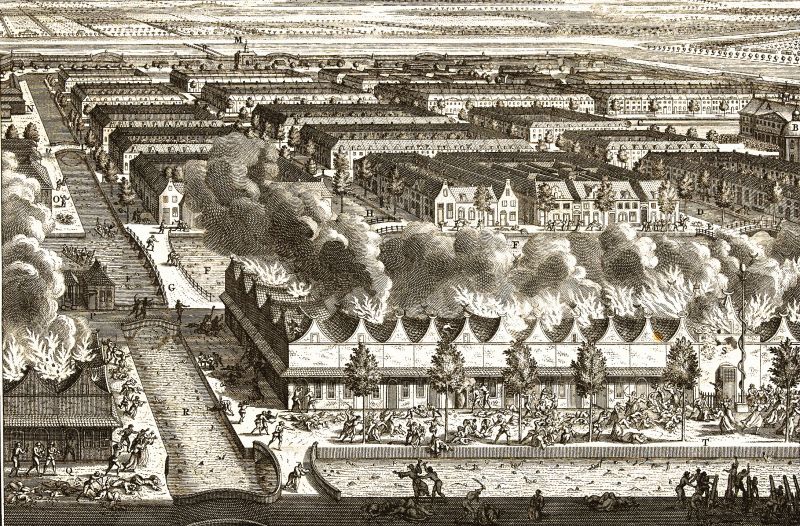

One event poisoned Chinese-European relations. This was the behavior of the Dutch at Jakarta (then known as Batavia) on the island of Java where a large overseas Chinese community had built up rapidly. In 1740 the Chinese community revolted over their abysmal pay and conditions. The Dutch reaction was brutal - the whole community of 10,000 people was slaughtered by the Dutch. Chinese trust in all European traders was greatly damaged thereafter.

In 1743 the British had an encounter which further soured relations. Commodore George Anson ➚ sailed the battle-damaged HMS Centurion (sixty guns) to Guangzhou to have his ship repaired, it was towing a captured Spanish galleon laden with silver. As he was not there to trade he did not expect to pay harbor dues and wanted to meet the Viceroy. He was refused permission and payment of normal dues demanded, so just like Captain Weddell did before him in 1637 he just sailed up the Pearl river to Guangzhou regardless with a very reluctant Chinese pilot held at gunpoint. He was refused all Chinese assistance at Guangzhou and he soon ran short of food. Anson fired a large cannon twice a day to remind the Chinese of his ship's power. It was only when he helped the Chinese put out a large fire in the city that he was granted an interview with the provincial Viceroy and allowed to leave with fresh provisions. On his return, his bitter report accused the Chinese of all forms of deceit and innate dishonesty. He thought that the use of Pidgin English gave the case for Chinese stupidity (pidgin was now in use rather than Chinese which Anson considered obtuse and impractical). He thought the Chinese were just imitators lacking creativity.

In 1756 Frederick Pigou, a director of the East India Company (EIC), suggested that Shanghai would be a suitable site for development. These plans were to come into fruition in the following century. In 1757, Captain James Flint sent a petition to the Chinese Emperor Qianlong complaining of being cheated of due payment by Chinese merchants as well as requesting the opening of trade at Ningbo, Zhejiang. His request was refused and instead resulted in further restriction on trade and Flint's imprisonment because it was most impertinent to expect the emperor to intervene in trade disputes and definitely not by foreigners. In the UK this became known as the notorious Flint Affair ➚.

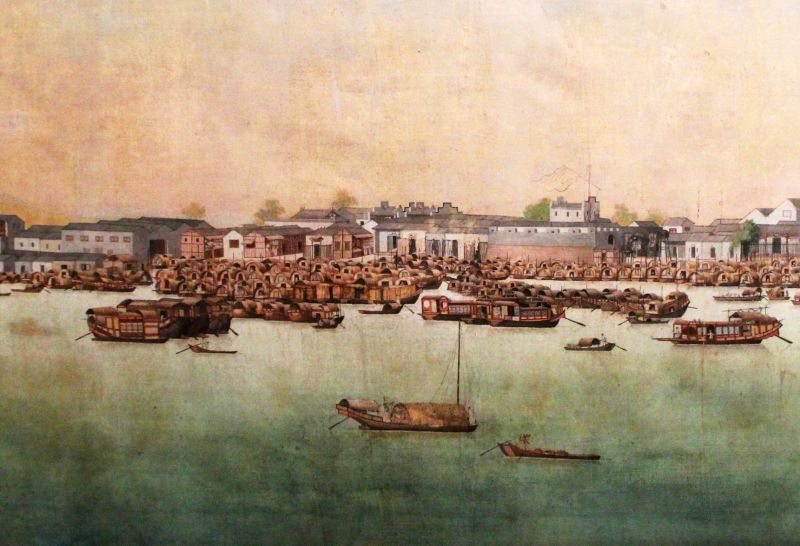

Flint's efforts led to the foundation of the Canton system in China to try to prevent further foreign effrontery. The Guangzhou (Canton) system established in the mid 18th century was hugely corrupt. It was administered by a guild of ‘hongs’ who could demand whatever tariffs they wished on goods. It was so lucrative that the three year appointment as a ‘hong’ had to be bought at a very high price. The first two year’s income went to pay the bribes to get the position, only the last year gave any profit to the ‘hong’. Above the hongs was the overall administrator the ‘hoppo ➚’ who in the early days had to be a Manchu. He was immensely powerful and subservient only to the Governor of Guangzhou and Viceroy of Guang (Guangxi and Guangdong were then administered as a single province 'Guang').

Undeterred, other European traders continued to try to set up trading posts elsewhere at Ningbo and Xiamen but the Qing government decreed all trade must be through Guangzhou, with very limited Spanish trade at Xiamen. The emperor considered it expedient to move the trade as far away from the capital as possible as he believed that foreign contacts, quite rightly, often led to conflicts and rebellions. In any case the traders at Guangzhou were keen to keep the monopoly and so be able to fix prices as high as they could get away with. Foreign ships were only allowed into harbor during the trading season, at other times they had to stay at Macau. Foreign hostility over these restrictions to trade continued to grow.

Then followed the Lady Hughes incident ➚ of 1784 where the death of two Chinese fishermen further heightened diplomatic tensions. The Chinese demanded the British seaman who fired a ceremonial cannon that had accidentally killed the fishermen must be handed over. The British captain refused, so then the Chinese halted all European trade. After some delay the seaman was very reluctantly handed over, only to be summarily executed by the Chinese.

During the 18th century Britain overtook Portugal, France and all the others to become the major trading nation at Guangzhou, fueled by its expansion to India as well as the ‘discovery’ of Australia by Captain Cook ➚ in 1770 and other new territories in the Pacific. Britain took a stranglehold of Chinese trade as the largest trading nation. However the East India Company was facing ruin over the tea trade because China demanded payment in silver and the newly independent United States refused EIC imports. This was a big deal, in 1759 the EIC bought 15% of all Chinese tea. It was in 1760 that the opium trade began - starting with only small amounts but the volume began to build up in the 1780s. Initially it was Chinese opium growers who were disadvantaged by the imports of pure, cheap opium, and so the government was pressured to protect domestic production. This topic is fully covered in our Opium Wars page.

In 1777, after gaining independence the United States of America was keen to set up its own direct trade with China. In 1784 the ‘Empress of China’ was their first vessel to dock at Canton. Early trade was in sea otter furs and sandalwood which had become very popular in China. The loss of the American colonies forced many British sea traders to look elsewhere for their markets. They became increasingly desperate to break into the China trade which remained the most prosperous and populous nation on Earth.

As far as most of these European and Americans traders were concerned China was a land of lofty isolation and aloofness brimming with self-serving officials full of self-conceit but this view was not shared by many people in Europe at the time.

The end of the Jesuit mission

Going back again to the start of the 18th century. During Emperor Kangxi's long reign (1661-1722) the Jesuits had high hopes in China. They helped educate the emperor's children in the western mathematics of Euclid as well as Christianity. However in 1705 a Papal mission resulted in a split between the Jesuit community and other missions as well as alienating the emperor. Then, in 1707, the Pope undermined the whole mission ➚ by deeming that ancestral worship was incompatible with Christian doctrine. The emperor responded by banning Christianity, expelling the missions and only allowing the churches at Guangzhou and Macau to remain. Kangxi's son and grandson continued to condone the persecution of Christians. The few remaining Jesuits were restricted to secular work - designing buildings (most notably the Old Summer Palace) and studying astronomy. In 1773 the Jesuit organization was disbanded by the Pope and the remaining Chinese missionaries either returned home or lived on in secret. So in the 18th century the direct link from the Chinese Imperial court to Europeans was lost and mutual misunderstandings grew.

European thinkers

Western intellectuals and writers were not interested in the woes of a few sea captains trying to make a fast buck in China, they wanted to learn about Chinese culture, religion and philosophy. The Jesuit mission had written extensively about China and the Vatican library held a great deal of information for scholars to study. In 1735 from these records and journals the French Jesuit Jean du Halde ➚ produced his encyclopedic ‘History of China ➚’ which became the standard text (translated into English in 1741).

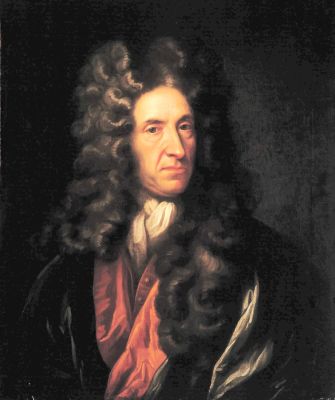

The favorable Jesuit view of a land of wise emperors surrounded by educated scholars persisted in the European mind into the start of the 18th century, but some influential writers began to shift their thinking. Daniel Defoe in 1719 published ‘The Farther Adventures of Robinson Crusoe’ with rather negative attitudes about China, he considered them backward in religion, architecture and that the army, boats, scholars and farmers were not up to western standards. Defoe wrote that the Chinese have ‘Contempt of all the world but themselves’.

Only a few Chinese men came to Europe and these were Catholic converts. About 10,000 European missionaries went to China but only 300 Chinese came to Europe. Jonathan Spence has written a short book ‘A Question of Hu ➚’ all about the huge pressures of such a life. John Hu came to Europe in 1722 and was exploited by a zealous French priest to translate Chinese texts, Hu ended up abandoned, living in squalor in a mental asylum, so it is not a happy outcome. One Chinese national who had a better time was Arcadio Huang ➚ who rejected his faith once in France (1704/5) and went on to influence the great writer and philosopher Montesquieu ➚. He married a Parisian and was fêted in fashionable circles. Unfortunately his wife and daughter died in 1713 and he died shortly after in 1715. Huang's collaboration with Montesquieu helped produce ‘The Spirit of the Laws ➚’ (1748) with a wide ranging look at types of government including examples from Chinese history. The book became a landmark in political theory that influenced the writing of the US Constitution.

A continental philosopher and mathematician of great influence over the whole of Europe was Gottfried Leibniz (see complete description here). He published a pamphlet ‘News from China ➚’ in 1699 full of praise. He considered Emperor Kangxi to be a great and learned ruler. He thought China surpassed Europe in many ways. Leibniz invented binary arithmetic and was encouraged in this by studying the Yi Jing (I Ching) believing that ancient Chinese had discovered the binary system. As all modern computers are based on binary we can see how Chinese knowledge has contributing to technological advancement. Leibniz was keen to open trade and debate with China through Russia (he corresponded with Peter the Great ➚). There was an invitation for Chinese scholars to come to Europe but this did not come to fruition. The history of relations might well have turned out differently if scholars had come to Europe. Leibniz in his later years (1716), did wonder if his enthusiasm had been too great and maybe the Chinese system of deference was based on slavish servitude rather than honor.

Matteo Ripa ➚ set up the first ever institute of Chinese Studies at Naples in 1732. Ripa was one of the few non-Jesuits to embrace Chinese culture. He brought back many Chinese converts to study there. The Naples school lasted until 1888 by which time 108 Chinese priests had been trained.

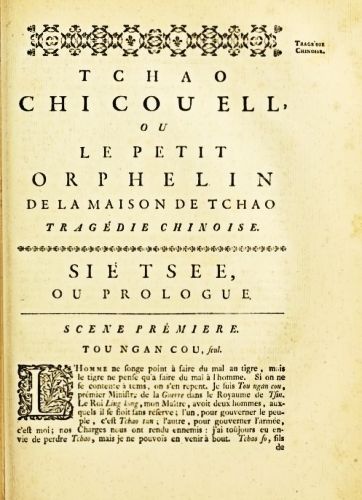

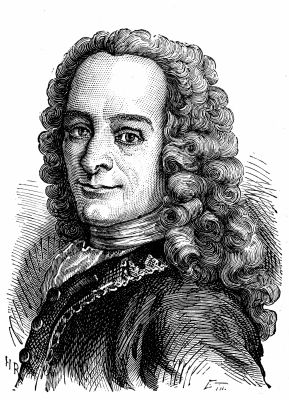

In 1741 the ancient Chinese play ‘The Orphan of Zhao ➚’ was translated and put on stage and proved very popular across Europe. The French writer and philosopher Voltaire ➚ (1694-1778) wrote his own version. In it the Chinese are shown to have superior moral values compared to their Mongol overlords. Voltaire eulogized: ‘The Chinese for four thousand years when we were unable to read, knew everything essentially useful of which we boast at the present day’. Voltaire started with broad positive appreciation of China but later thought it had not developed to its full potential, for example, improvements to its many inventions. He thought it was held back by its undue respect for the past, and its complex language. Later on though, in 1755, Voltaire changed his mind and thought Chinese science was empirical rather than based on sound theory.

Some fraudsters made use of the popularity of the Chinoiserie fad for all things Chinese, George Psalmanazar ➚ (1679-1763) wrote a totally fabricated book about Taiwan in 1704 with proved popular.

In France a major proponent of Chinese ideas was François Quesnay whose book ‘Le Despotisme de la Chine’ (1767) described his understanding of the Imperial system and the use of promotion by merit and universal education. It is Quesnay's attitude that may have brought the phrase ‘laissez faire’ into widespread usage - reflecting the laid-back attitude of many officials in China. His description of Chinese intensive agriculture from Feng Shui and Daoist thought influenced French farmers. His knowledge and enthusiasm for China led to him being termed the ‘Confucius of Europe’. King Louis XV even imitated the Chinese emperor's spring ritual by plowing a furrow in 1756. In general terms Chinese civilization and culture had huge influence in western Europe.

The positive European view was shared by the UK at the start of the 18th century. China was seen as the top nation with benign and well educated leadership. This can be seen in Oliver Goldsmith's (1728-74) work. In 1760-61 he published his ‘Citizen of the World’ better known as the ‘Chinese Letters’ which proved extremely popular. In these letters he pokes fun at English fashion, class and behavior from the perspective of a fictional Chinese gentleman. The fact that he chose Chinese as the nationality of a person who was erudite, cultured and perceptive speaks volumes about the general attitude to China at the time.

However the view about China changed in the UK before the rest of Europe probably from the experiences of traders and diplomats like Captains Anson and Flint. Horace Walpole ➚ (1717-1797) influential son of the longest serving Prime Minister Robert Walpole wrote a satire on the taste for everything Chinese: ‘Mr Li: A Chinese Fairy Tale ➚’ in 1785. It marked the turn away from idolizing China; Britain now chose Classical Greece and Rome as the civilization to be emulated rather than China.

Diplomatic Missions

In total there were six embassies to China in the period 1656-1753. Two were Dutch, two Russian and two Portuguese; only one of the Russian missions got anywhere near the Imperial court. As well as the sea route to southern China there was the overland, northern route through Mongolia into Russia and then to Europe.

Joining the Russian mission of 1714 was Scotsman John Bell ➚; he had graduated as a doctor at Edinburgh University and then went to seek his fortune in Russia. He published his memoirs ➚ in 1763 in which he describes the trip in a matter of fact manner, in contrast to the religious/philosophic viewpoint of the Jesuits. He crossed the Great Wall and found it a very impressive construction. They were granted an audience with Emperor Kangxi for which they were forced to kowtow despite protests. Bell considered the emperor sprightly for his age of sixty. He was impressed by the acrobats and jugglers that he saw. Unlike Marco Polo he noticed how the women used foot-binding. Overall he was positive about China - he considered the people generally trustworthy but with a few idle liars. The Russian mission concluded that while they could quite easily conquer the country but they could see no point in disturbing the peace and good governance.

In 1727 Russia managed to sign a new treaty with China - the Treaty of Kiakhta ➚ - which was the main frontier post for the tea trade with Russia. Kiakhta is situated north of Ulan Bator on the Mongolian border. Russia had already signed a deal (written in Latin) - the Treaty of Nerchinsk in 1689. The success of the Russians in signing treaties with China must have rankled with the other Europeans keen to do the same.

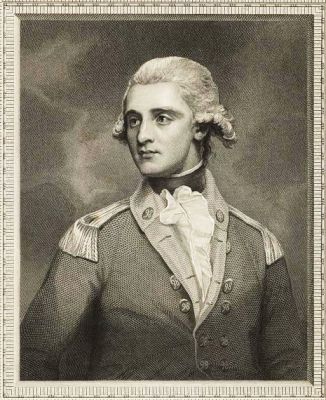

A British mission to China led by Lt. Col. Charles Cathcart ➚ of the EIC set off in 1787. He unfortunately died in transit off Sumatra and the mission was abandoned. This was soon followed by the massive Earl of MacCartney mission of 1793/94.

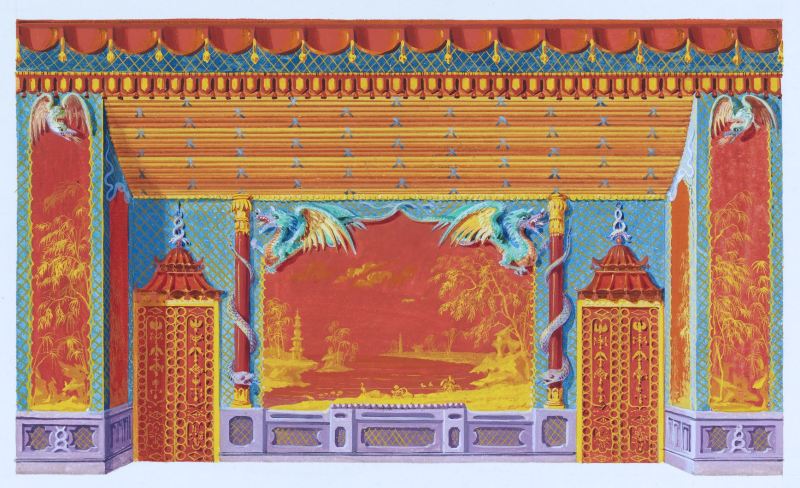

Chinoiserie

The thoughts of merchants, intellectuals and diplomats had little impact on ordinary people. In the UK the perspective, at the start of the 18th century, was China as an exotic almost mystical land far away. What they could see with their own eyes was the exquisite workmanship and taste of Chinese manufactures - particularly silk, ivory and lacquer-work. They were stunned by the light, thin porcelain. The heavy, dull, brittle European earthenware goods bore no comparison.

So in the first half of the 18th century China supplied the must-have goods unmatched in Europe. The fashion for anything Chinese was born. The genuine Chinese goods were far too expensive for the masses so Europeans set about making cheap imitations. ‘Chinoiserie’ was the French term used for these wares that adapted Chinese style to European tastes. It is these rather strange mixtures of European and Chinese styles that make up the bulk of Chinoiserie. Initial designs were crude caricatures of the genuine articles, but over a hundred years the designs became much more like the real thing.

It was the rapid addiction to the new mania for tea drinking that gave Chinese style great impetus. What could be more appropriate than to drink Chinese tea in Chinese style teacups? Once people took to teacups then why not expand the style to the whole room in which to drink the exotic and very expensive new beverage? In the early days of tea drinking remnants of the Chinese tea drinking ceremony were followed - it was a rather formal affair. Among fashionable circles the competition to show off the finest and latest porcelain tea services became intense.

Not just porcelain but silk and lacquer-work influenced design. Chinese style gardens became the norm. Chinese Pavilions were built and Kew Garden's Pagoda ➚ shows how influential this style became. Both King George III and George Washington wore pigtail wigs in deference to the Queue biànzi forced on the Chinese by the Manchus. It is ironic that western leaders unwittingly chose a style that professed subjugation to the Qing emperors.

An example of the move away from Chinoiserie can be seen at the Royal Pavilion at Brighton ➚, UK. It was built in 1787 in a strange Indo-Saracenic style but the interior had many objects in Chinoiserie style. The Prince of Wales (later King George IV) was a slave to fashion and the change in taste from Chinese to Indian and Classical came about at the end of the 18th century. Elsewhere in Europe Chinoiserie clung on for longer, even into the early 20th century in places.

Ordinary people noted the change too. Porcelain began to be made at Sèvres, France in 1756 and Royal Worcester, UK in 1751. European manufacturers began to be able to achieve the same fine quality as Chinese goods by spying on and copying the Chinese process. Some commentators believe the European advantage was mainly in more efficient manufacturing and delivery of goods than from far away China. The transition to home-made goods accelerated now that the Industrial Revolution had begun in the UK. It was only the addiction to tea that made continued trade with China essential.

For further details all about the Chinoiserie style please see our separate article.

Qing ascendancy

The 18th century in China is regarded as a spell of good government and continued overall improvement. The first four Qing emperors Shunzhi, Kangxi, Yongzheng and Qianlong ruled long and skillfully, their reigns covered 150 years of relative prosperity for all in China. The Manchu people introduced some wise reforms and accepted Confucian orthodoxy in government.

The defeat of Mongol leader Galdan in 1696 at the battle of Urga pacified the northern border, and enabled the subsequent conquest of Xinjiang in 1759. The annexation of Tibet helped pacify the Mongols because they had embraced Tibetan Buddhism. Use of European designed artillery proved crucial to the military superiority of Qing forces. At around 1750 China remained the largest, strongest, wealthiest and most populous nation on Earth. Most historians consider the decline of the Qing to begin on the death of Emperor Qianlong in 1795. He was followed by a series of short-lived and ineffective emperors who failed to modernize and adapt to the growing threat of the west.

Contending perceptions

All that the Chinese imperial court could see in its dealings with Europeans (and Americans) were squabbling adventurers who behaved little different to the pirates which continued to harass boats in the South China Sea. The different European ‘tribes’ were hard to distinguish and their different brands of Christianity (Catholics, Protestants, Methodists,...) were baffling. China had often had issues with ships from far away but they had always been just a short term nuisance as the boats soon had to go back to their home shores. What China failed to notice was that the British now had a huge base on their western border - India. An army could be raised in India, it did not need an Armada to come all the way from Europe. The sheer number of ships that could easily reach China made previous calculation of threat out of date. China has always been a land based civilization, the coming of peoples by ships did not impress, Confucius after all considered the influence of the sea as evil. Few in China ever saw the sea and they came to think the British were a strange people who lived their whole lives on ships.

The British perspective was that they had built a benign administrative system in India. The administrators made fortunes in India every bit as immense as the Canton hongs. To treat these British lords (‘Nabobs ➚’) like pirates was a severe Chinese miscalculation. This shift from just trading with India to ruling the country began around 1740. The famous Lord Clive of India ➚ arrived there in 1744 and began building an impressive army recruited from among the Indian kingdoms. His experiences led Lord Clive to say in 1763 that it would be easy for Britain to conquer China. He considered China to be in little better condition than the Indian princely states that had been so easily subjugated. All this had been done under the aegis of a private company, the English India Company (EIC). A company with a large army seems a strange idea even today, this and other factors required structural changes that failed to be made in China.

The Macartney Mission of 1794

By the end of the 18th century the battle lines were clearly set out. Europeans (especially Britain) and China both viewed each other as inferior barbarians. In 1793-4 the great EIC mission of Lord Macartney set out to negotiate with the aging Emperor Qianlong. Macartney came well prepared, taking with him every book he could find about China, by contrast it seems China had little idea about even where Britain was located. Whole books have been published about this momentous clash of civilizations and so we have dedicated a whole section to describe this next important stage in China's contacts with the west.