Chinoiserie - a brief worldwide addiction to Chinese style

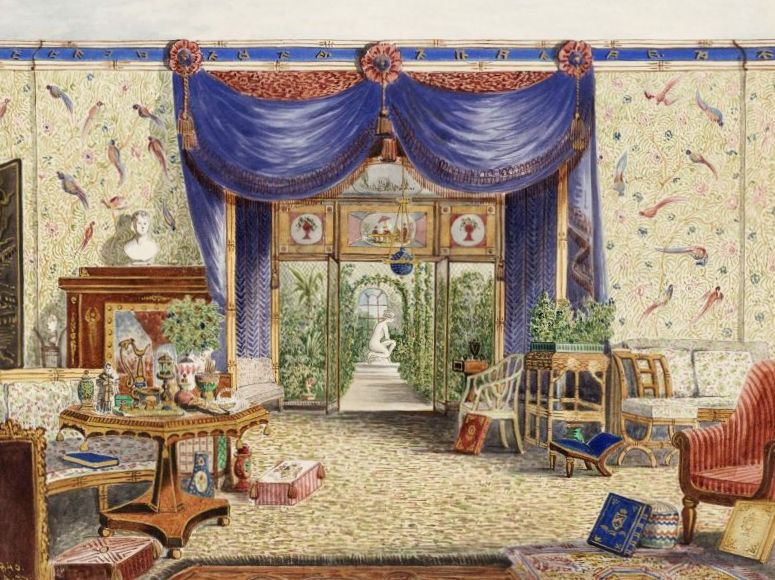

There was a time when anything Chinese was avidly collected in both Europe and America. Grand mansions would have a ‘Chinese Room’ stacked high with gleaming, colorful porcelain in display cabinets and outside a Chinese inspired garden. To belong to fashionable circles you just had to have Chinese ornaments, silks, lacquer-work, furniture, willow pattern plates, sedan chairs, wallpaper, gardens with pagodas… everything. From the mid-17th century through to the early 19th century there was a great fashion for the ‘Oriental style’ and in France it was given the name ‘Chinoiserie’ where the fashion reached its height of popularity.

From long ago China had already been known as the source of the most refined porcelain and silk. No European manufacturer could come close to the fine detail and overall quality. However the real spur to the new style were the detailed survey of life in China by the 17th century Jesuit missionaries. They described a nation ruled wisely by knowledgeable rulers who were guided by wise philosophers. China was seen as a distant, idyllic land full of the best of everything. Indeed it was true that China was at that time the richest, the most developed and the most populous nation on Earth. William Shakespeare, John Milton, Goethe, Leo Tolstoy and Henry Purcell all wrote of China as a distant paradise. Meanwhile in America Thomas Jefferson and Benjamin Franklin were impressed by the rural simplicity of China. It seemed an idyllic peasant life under a benign leadership. The French philosopher Voltaire ➚ eulogized: ‘The Chinese for four thousand years when we were unable to read, knew everything essentially useful of which we boast at the present day’. The Dutch traveler Johan Nieuhof ➚ (1618-72) was an important influence because his books not only carried descriptions but fairly accurate illustrations of all things Chinese. His book ‘An embassy from the East-India company of the United Provinces, to the Grand Tartar Cham, or Emperor of China’ was quickly translated into English and became very popular.

Although the rich and powerful could afford to import the genuine articles the middle classes could only buy cheap imitations either made in Europe or made in China especially for export. It is these rather strange mixtures of European and Chinese styles that make up the bulk of ‘Chinoiserie’. Initial designs were crude caricatures of the genuine articles, but over a hundred years the designs became much more like the real thing.

Pigtails and gardens

George Washington had a fine collection of porcelain and took to wearing a wig with a long ‘pigtail’ in deference to the Chinese hair style of the Qing dynasty. The British King George III also used the same hairstyle and his son King George IV built rooms full of Chinese porcelain masterpieces at his Brighton Pavilion ➚. Lord MacCartney, one of the very few who had actually visited China in 1793 enthused about how Chinese gardens used subtle design and planting to generate surprise and wonderment. By contrast the European gifts he gave to the Chinese Emperor failed to impress.

It was the rapid addiction to tea drinking that gave Chinese style even more impetus. What could be more appropriate than to drink Chinese tea in Chinese style teacups? Once people took to teacups then why not expand the style to the whole room in which to drink the exotic and very expensive new beverage? In the early days of tea drinking, remnants of the traditional tea drinking ceremony were followed, it was a rather formal affair. Among fashionable circles there was intense competition to show off the finest and latest porcelain tea services.

Chinoiserie was the European interpretation of Chinese art with exuberant decoration and asymmetry. At its height it was a worldwide phenomenon not just in Europe and America but also in India, Japan, Persia and Latin America. King Louis XV (r. 1715-1774) was a leading proponent. He brought in many Chinese ideas and customs; this came to its zenith when in 1757 he guided a plow to welcome in the spring in a ceremony mimicking the Chinese Emperor's ritual at the Temple of Heaven every year. His Chateau de Chantilly ➚ built for the Princes of Condé is an exuberant example of Rococo/Chinoiserie style.

Citizen of the World

Oliver Goldsmith (1728-1774) had read de Halde's extensive guide to China (‘The General History of China ➚’) and it inspired him to write the highly popular ‘Citizen of the World’ 1760-61. They are a fictional correspondence between a Chinese man living in London and his acquaintances back in China. They show the anonymous Chinese man in a favorable light trying to make sense of life in Europe with its strange customs and lower moral standards. It was not long before writers satirized the fad for Chinoiserie, in 1785 Horace Walpole’s ‘Mi Li, A Chinese Fairy Tale ➚’ poked fun at the unquestioning love of China.

There was a dreamy belief that the Chinese had the greatest aesthetic taste in all things. In 1664 John Evelyn was deeply impressed by the exquisite and refined workmanship of garments and ornaments, quite unlike the crude nature of European products.

The art historian H.A. Crosby Forbes (1925-2012) wrote “The artisan community of Canton [Guangzhou], with its porcelain and enamel painters, its painters of oils and watercolors, its weavers and embroiderers, its silversmiths and other metal-workers, its carvers, gilders and cabinet makers, produced more goods of consistently high quality and good taste, in greater quantity over a longer period of time, than any other artisan community the world has ever known.”

When the Neo-classical fashion took hold in the mid-18th century the fashion went into decline in Britain. England led the move by seeing ancient Greece as the model to follow not China. In addition more recent accounts of China, mainly by traders, moderated the glowing testimony that the Jesuits had written. On continental Europe the respect for all things Chinese hung on longer; it was the death of the writer, thinker and Chinese devotee Johann von Goëthe ➚ [1749-1832] that marked the start of the decline.

In the end Chinese manufacturers lost out as although they could manufacture cheaply; packaging and transport were poor and so European imitators had a distinct advantage. When opium addiction took hold and Britain (with France) took to war in the 1840s the view of China turned to disdain.

Ceramics

In pottery, Europeans did not initially appreciate the austere beauty of Song dynasty celadon wares, they chose the brightly colored wares instead. This led to the development of ‘famille rose’ as well as 'pink' and white glazes which made porcelain more attractive for export to Europe. Cloisonné work ➚ also was popular overseas from the Ming dynasty onwards, in this detailed work has areas edged with very fine wire to prevent the enamel spreading and so producing sharp edges.

The European colonists took the addiction to Chinoiserie with them to the Americas. There was soon an active market for the real items and American pirates often attacked the heavily laden boats on their way back from China to Europe (at this time they sailed the long way via the Cape of Good Hope). It was the English East India Company monopoly on the China trade that fueled this move to American independence.

And everything else...

Not just porcelain and architecture were influenced, furniture was made in the Chinoiserie style too. Thomas Chippendale ➚?s design book ‘The Gentleman and Cabinet-maker?s Director’ brought the style into furniture, but in this case this was more in terms of decoration rather than shape.

It is important to also remember that for a while it was not only objects that were bought and admired but social customs as well. For example sedan chairs were briefly popular, and not only the concept was copied but the Chinese customs and etiquette associated with them including appropriate colors to indicate the rank of the occupant. In the mid 18th century the great thinkers took up Chinese philosophy. For example a book was written around the imagined dialogue between Confucius and Socrates.

Royal Palaces

An example of the transition away from Chinoiserie is the Royal Pavilion ➚ at Brighton, UK. It was built in 1787 in a strange Indo-Saracenic style. The interior had many Chinoiserie objects. The Prince of Wales (later King George IV) was a slave to fashion. Frederick Crace was the principal interior designer and he freely mixed Indian, Chinese and Japanese design motifs - Chinoiserie was never purely Chinese but more broadly ‘Oriental’.

When in 1825 he became King George IV he employed Jeffrey Wyatville to build, a grand ‘Fishing Temple’ at Virginia Water, near London with huge Chinese style pavilions of glass and wood. One was called ‘The Mandarin’ and floated on the lake with painted dragon motifs. The whole expensive edifice collapsed into the waters within 75 years and nothing now remains. By the time Queen Victoria ascended the throne in 1837 Chinoiserie was at an end and she sold off the Brighton Pavilion and built Osborne House ➚ on the Isle of Wight in the Italianate style.

Another example of exotic and strange use of the style is at the ‘Chinese Dairy’ at Woburn Abbey ➚, Bedfordshire, England built between 1787-1802. The Duke of Bedford wished to build a large Chinese garden and the centerpiece was an eccentric working dairy . It was designed by Henry Holland and made with lattice work designs in marble and wood, the dairy was joined to the house by a covered walkway. As well as actually milking cows the building housed the duke's fine collection of Chinese porcelain.

Chinese-style Gardens

Chinese garden design had to be adapted to European tastes. Chinese gardens are generally in the center of courtyard house - with rooms all around them - the garden is on the inside. European houses are built the other way around - looking outward rather than inward. Lord Macartney and John Evelyn were great admirers of the informal style of Chinese gardens particularly because the existing style had become one of geometrically regimented symmetric designs - as at King Louis XIV's Versailles. The natural look of a Chinese garden was in complete contrast. Sir William Temple developed the form ‘Sharawadgi ➚’ as a naturalistic landscape inspired design. The main element was asymmetric naturalism with the garden split into compartments revealing ‘surprise’ vistas. Although Chinese inspired, the design had to fit with the open landscape of lawns and trees of the European houses rather than inner courtyards.

The Kew Pagoda

One of the most famous and largest examples of the style is also in the UK. At Kew Gardens the ten floor Great Pagoda ➚ was completed in 1762. The gardens were laid out with a large number of classical style ‘temples’ among trees and shrubs rather like the Old Summer Palace at Beijing. They were the first gardens to embrace the Chinese style in Europe. As well as the pagoda a ‘House of Confucius’ was built - but demolished in the early 19th century. The pagoda designed by Sir William Chambers is octagonal in shape and located to be the final tour de force of a visit to the gardens. It was the most accurate Chinese style building outside China at the time. It still stands 164 feet [50 meters] high with commanding views over west London.