Chinese Christianity

Christianity reached China as early as the 7th century. This was the Eastern form of Christianity sometimes known as Nestorianism ➚; in China it was called Jing jiao 景教 and associated with the Roman world. Jesus is transliterated as 耶稣 Yē sū in Chinese. Ishoyabb II ➚ sent a delegation to the Tang Emperor Taizong in 635. This mission led by bishop Alopen ➚ (his Chinese name) was welcomed. The faith converted some senior officials, eunuchs and concubines and had a brief but wide influence. A monastery was founded at Zhouzhi 45 miles south-west of Xi'an, Shaanxi. It could well be that this community is the origin of the ‘Prester John ➚’ legend that circulated Europe at times between the 12th to 17th century; which was that an isolated Christian kingdom existed in the distant East. Some of this became conflated with the rise of Genghiz Khan's great empire as he had Christian connections. The famous Nestorian stele (an inscribed stone slab) was erected in 781 at Chang'an, the inscribed text expresses Christianity in Buddhist/Daoist terms. The stele's discovery in 1625 was used by the Jesuit missionaries in Beijing as evidence of Christianity's long standing status as a religion in China. The Manichean ➚ faith which is considered a mix of Christianity and Zoroastrianism also prospered during the Tang dynasty until the brutal suppression of all 'foreign religions' in 843 by Emperor Wuzong. There was no widespread support outside Imperial circles so the Christian community disappeared. A visitor to Baghdad in 987 reported that he had found in China that all the Christian churches lay in ruins and there were no Christians to be found.

The isolated Jewish community at Kaifeng fared better, it lasted about one thousand years and when it was discovered in the 19th century it caused great excitement.

During the Yuan dynasty, the Mongols welcomed people from many countries including Christians such as Marco Polo. The Mongols under Genghis Khan had tolerated a version of Christianity adapted to the Mongolian culture in 1007. Genghis's mother was a professed Christian and the mongols often wore the Cross motif. During Kublai Khan's rule of China Dyophysite ➚ Christians were prominent at the Imperial court and the religion enjoyed a brief flourishing. In 1280 a Mongolian Christian convert, Rabban Sawma ➚ traveled all the way from China to Constantinople, Rome before meeting the Pope Nicholas IV at Bordeaux. From about 1365 onwards nothing is known of the fate of the Nestorian Christians in China. However during the start of the following Ming dynasty this 'foreign' religion dwindled. It was seen as relating to the hated foreign Mongols and rigorously suppressed. At the start of the Ming, in 1371, an ambassador was sent to Rome (known to the Chinese as Da Qin ➚) to inform the pope of the founding of the new dynasty.

Towards the end of the Ming dynasty an important Jesuit mission to China was led by Matteo Ricci SJ. He was a member of the Jesuits and decided to focus their efforts on converting the Emperor and senior court officials to the faith rather than the poor of coastal towns that other denominations were targeting. They were trained in mathematics and astronomy so they could impress the Imperial elite into taking their religious teachings seriously. Although they made early advances the fall of the Ming dynasty in 1644 led to a gradual diminution of their influence and the numbers of Christians dwindled. The last Dowager Empress Wang of the Ming dynasty converted to Christianity and her son (Zhu Youlang ➚) was baptized a Christian in 1648 but he fell into Manchu hands and died in captivity. This move was partly made in the hope that the European Christians would help her restore the Ming dynasty to power. In the seventeenth century other missions by Dominican; Franciscan and Cistercian established brief footholds in the southern coastal ports. The Dominicans and Franciscans went among ordinary working people, but Jesuits lived in luxury among the educated elite.

The Catholic ritual of the Jesuits was considered to be one of the many ancient rituals of China and this led many to consider that conversion would be easy. Julian Bertrand wrote “If our church was free to display the full splendor of its ceremonies before the eyes of the Chinese, if the harmonious sound of the organ could reach their ears, fountains of water would not suffice to baptize all the converts there would be.”. Jesuits believed that ritual was the key factor, other missionaries concentrated on distributing short religious tracts.

The Confucian elite at court found the crucifixion distasteful, Jesus was not portrayed as an educated man, just a brigand who met with a violent, gruesome death. Chinese heroes were usually aristocrats and scholars who at worst died honorably in battle. The Cross was seen as a black magic totem by many people. These views evoked hostility to the new faith among many senior figures.

Jesuits were men of science as well as religion. In fact Adam Schall complained about spending too much time on science rather than missionary work. European skills in cartography led the Qing emperor Kangxi to task the Jesuits with production of a map of the entire Chinese empire. Their map of the world showed China not at the center but on the fringes of the world. This challenged the age-old view that China was the center of civilization with only a few barbarian states scattered around it. However it was the new European methods in astronomy that really impressed the Chinese. Matteo Ricci translated the Elements of Euclid ➚ into Chinese for the Emperor to read. The Jesuits were considered 西儒 xī rú ‘western scholars’. Emperor Kangxi became a close personal friend of Adam Schall and used to frequently visit him. Adam Schall and Ferdinand Verbiest followed Ricci and won a competition to make the most accurate prediction of a solar eclipse with the Chinese astronomers who used traditional methods. They succeeded because Chinese astronomical knowledge had relied on methods that were no longer fully understood and so could not be refined. The Jesuits took up Imperial posts at the Bureau of Astronomy in 1629 and revolutionized Chinese astronomical methods. Some of the instruments still to be seen at the Beijing Observatory ➚ were designed and built by them. They also helped design parts of the new Qing Old Summer Palace using the latest European architectural style and novelties such as water fountains. Most of the missionaries came from Portugal because of the privileged access via Macau, a few Spanish missionaries did come to China via Acapulco and Manilla. The granddaughter of one of the initial Three Pillars converts, Candida Xu ➚ proved an influential convert. Her biography written by Philippe Couplet was immensely popular in Europe.

The Jesuits were keen to show that the Chinese classics were compatible with the Bible and showed a shared cultural heritage. Joachim Bouvet ➚ (1656-1730) was a Jesuit who took great trouble to convince the Emperor that the Yi Jing (the foremost Confucian classic) was full of Christian thought and was full of strong parallels with the Bible. Bouvet for a while spent two hours a day exploring the meaning of hexagrams with Emperor Kangxi. He also tried to show even the structure of Chinese characters was full of Christian symbolism. Such an accommodation would have brought Chinese and Christian civilizations together. A particular stumbling block for the mission is that most Christian tradition at the time looked towards the end of the world at Christ's Second Coming. However Chinese philosophy has always favored a cyclical evolution over time, not a one way arrow of time.

The convert Shen Fuzong was brought back by the Jesuits to Europe. He was greatly admired and met many kings and scholars. Shen spoke in Latin. He helped the British sinophile Thomas Hyde catalog the Chinese books at the Bodleian Library ➚, Oxford. His visit stimulated further interest in China, particularly as conversion to Christianity was evidently possible.

However Chinese suspicions continued. The young Emperor Shunzhi (r. 1643-1661) was very close to the Jesuits, it is said Adam Schall visited the emperor's bedroom and was referred to by the emperor as 'grandpa', this led to much envy and gossip. after the death of the Emperor Shunzhi (1661) who had supported them, memorials were written by high officials to the new Emperor Kangxi :

“The Westerner Adam Schall was a posthumous follower of Jesus, who had been the ringleader of the treacherous bandits of the Kingdom of Judea. In the Ming dynasty he came to Beijing secretly and posed as a calendar maker in order to carry on the propagation of heresy. He engaged in spying out the secrets of our court. If the Westerners do not have intrigues inside and outside China why do they establish Catholic churches both in the provinces and in strategic places in the provinces? During the last twenty years they have won over one million disciples who have spread throughout the Empire. What is their purpose? Evidently they have long prepared for rebellion. If we do not eradicate them soon then we ourselves rear a tiger that will lead to future disaster.”

As a result of hostility the Jesuits were put on trial in 1665 and found guilty of sedition. Five converts were sentenced to death and the Jesuits sentenced to flogging and exile. However, divine intervention struck, the day after the judgment a major earthquake hit Beijing and the Emperor seeing this as a portent reversed his judgment on the Jesuit astronomers but the converts were still executed. An underlying issue was that in China scholars and priests were two entirely separate professions, Jesuits attempted to be both at the same time.

It is misleading to think of the Jesuit mission as one of imparting European knowledge to China, it was very much a two way transfer. Documents at the Vatican demonstrate the huge interest in Chinese science and technology back in Europe. It has been suggested that leading philosophers such as Leibniz based their discoveries on this new information. Fascination with all things Chinese led to the fashion for Chinoiserie in Europe, many stately homes had a 'Chinese room' in the 17th-18th centuries.

Papal intervention

Another stumbling block for the Jesuit mission was one of doctrine. Matteo Ricci believed that the way to convert the Chinese was to adapt the Christian message to reflect Chinese heritage. One problem was how to translate God into Chinese. The Jesuits favored 上帝 shàng dì as that term referred to an existing supreme deity in China. Others thought this was too accommodating and wanted a new term such as 天主 tiān zhǔ. Another difficulty was there was no widespread belief in creation, human society was viewed as ongoing without worries of how it began or might end. There was also no concept of a supreme being controlling all things. But most difficult of alll was accommodating the ancient rite of ‘ancestor worship’ as a mere folk custom without religious overtones. After a century of debate the Pope outlawed the Chinese rites ➚ in 1707, undermining the efforts of hundreds of missionaries in China. The Emperor responded by banning the religion, expelling the missions and the only churches allowed to remain were at Guangzhou and Macau. For ordinary Chinese, these missions were greeted, in the main, by incomprehension and hostility and did not persist. Part of the problem was that traders had infiltrated the missionary ranks, in 1703 Emperor Kangxi commented that among the missionaries were: ‘mere meddlers ... out for profit, greedy traders who should not be allowed to live here... I fear that some time in the future China will get into difficulties with these Western countries’.

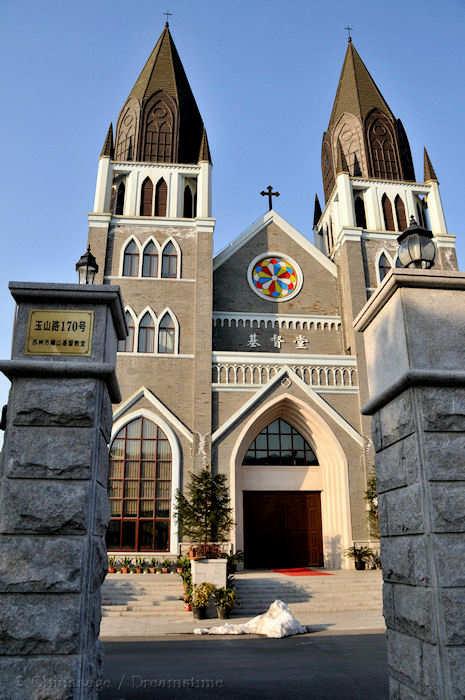

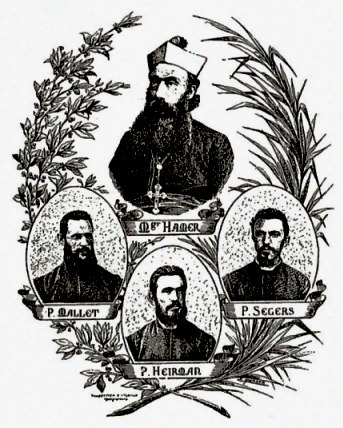

Western missions to China of many different denominations began in earnest in the nineteenth century, prior to 1800 all the main missions had been Catholic. The protestant missions rejected the Jesuit views of the Chinese people and Confucianism, regarding them much more disparagingly. Missionaries in the early 19th century began to receive rigorous training before their voyage to China. After missionaries were given free rein after the second Opium War (1860) more liberties were taken. Newly appointed bishops demanded and were given the same privileges as provincial viceroys. Any Christian convert was deemed to be subject to foreign laws not Chinese laws and so missions attracted people evading justice. The churches themselves were a cause of unrest as many were built in the western tradition - tall and imposing stone structures which violated the local traditions of feng shui. As they were seen as part of western colonial plans they were widely distrusted. For example many missions were keen to take in the sick and orphan babies for inexplicable (to the Chinese) reasons. The Eucharist posed problems too as women were in close contact with male priests - violating the rules of strict separation. The benevolent actions of schooling, medical care and even printing put the local skilled locals out of work. Missionaries were targeted and killed during the Boxer rebellion (thousands of Chinese converts; about 200 Protestants and many Catholic missionaries).

The missionaries for their part often had a rather patronizing attitude to the poor ‘barbarians’ they had come to save and had little to do with them apart from church services which were mainly for singing. Attitudes began to change from the 1880s when T. Richard, W.A.P. Martin, Y.J. Allen and others began to take account of Chinese traditions and founded schools, libraries and universities. Their message became one of salvation through reform of the Chinese state and reached the ears of such men as Li Hongzhang and Sun Yatsen (who became a Christian).

Modern adoption

A second spurt of Christian missions in the 1920s was brought to an abrupt end in 1951 when the Communists sought to extinguish all influence by foreign countries and even indigenous religions. Priests were subjected to 'struggle sessions'; churches and Bibles were confiscated. Because many Christian missions were supported by unfriendly foreign states (especially the US) so all the local Chinese who attended church were suspected of sympathy with foreign powers. It has only been since the 1980s that Christianity has been allowed to grow in China, particularly in urban centers; even so because control by foreign agencies is not permitted by the Communist Party there remains a particular problem for Roman Catholics who are not allowed to take direct orders from their leader the Pope. The government remains concerned that the unofficial, underground churches may form seditious mass movements rather like the Falun Gong sect ➚.

There continues to be confusion about the total number of Christians in China. Estimates consider that there are about 60 million protestant Christians in China and the numbers are growing rapidly. Because of the huge population of China it is quite possible it will be the most Christian country in the world within forty years if this growth rate continues. However, it has to be borne in mind that the traditional Chinese attitude to religion has continued. A Chinese person will attend Christian, Buddhist and Daoist ceremonies in the same month or even the same day and not feel any sense of disloyalty. Some Chinese have been interviewed and profess they like a Christian service not because of its religious appeal but because they like singing together.

Matteo Ricci 利玛窦 [6 Oct 1552 - 11 May 1610]

The Italian Matteo Ricci was one of the first to build a bridge of understanding between Europe and China in the late 16th Century. Members of the Society of Jesus ➚ (Jesuits) founded in 1540 by Ignatius of Loyola ➚ sought to convert the vast population of China to Catholic Christianity. Up to 900 Jesuits took their European knowledge to China. They had been carefully taught in the disciplines such as astronomy that they believed would be of use in China. It soon became clear that the way to convert the Chinese was to persuade the Emperor and his court to embrace or at least endorse the religion rather than convert his subjects.

Ricci reached Macau, China in 1582 and spent some years in the southern provinces where he mastered the language and culture. He took to wearing the garb of a Confucian scholar to gain acceptance. Ricci came to court in 1601 where he described China as ruled by a philosopher élite - close to the Platonic ➚ ideal for state governance. Although never meeting Emperor Wanli himself he was feted by the Imperial court. The insular and paranoid scientific culture at the time banned the independent study of science, science was only for the appointed officials at court; so Ricci had his books on mathematics confiscated. Matteo Ricci became skilled in the language and culture of China, and wrote books in Chinese. He was known by the Chinese name 利玛窦 Lì mǎ dòu. His Chinese friends admired his memory skills; he is believed to be able to instantly memorize a page of 500 Chinese characters recalling them in either forward or reverse order; to achieve this feat he used a technique called memory palaces ➚. Matteo devised the first transcription of Chinese into Latin letters, centuries before pinyin was created. They also appreciated the artifacts he had brought from Europe and the latest maps of the world but Ricci was careful to provide a map centered on China rather than Europe.

Ricci succeeded in converting three leading scholars at court (the Three Pillars of the Early Christian Church ➚: Xu Guangqi; Li Zhizao and Yang Tingyun) as well as a number of eunuchs and concubines. The fall of the Ming dynasty in 1644 proved fatal to the Jesuits' ambitions. Some Jesuits stayed with the Ming loyalists who fled south, others turned their efforts to convert the new Manchu conquerors. Seeking support from the ‘foreign’ Manchus for a ‘foreign’ religion further alienated the Han Chinese at court and led to a long term decline in Christianity. Another cause for decline was division between the different missions, the Franciscan and Dominicans worked in poverty among the poor while the Jesuits lived a life of luxury and accepted ‘heathen’ practices.

On his deathbed in 1610 Matteo Ricci was confidant of the eventual success of his Christian mission he said ‘I leave before you an open door’. Matteo Ricci is buried with a number of his Jesuit fellow missionaries in a small Christian cemetery ➚ in Beijing. His work was continued by the German Johann Adam Schall von Bell ➚ and others in China.