The Chinese Night Sky: Stars, Constellations and Mansions

The Chinese took a different path in their study of the stars in the sky than other cultures.There is considerable overlap between the study of the stars and that of the moon and sun that give us the traditional calendar . The study of the motion of the moon, planets and sun required complex mathematical calculations that was carried out by the elite astronomers at the Imperial Court. On this page we look at the ancient Chinese series of constellations and asterisms ➚.

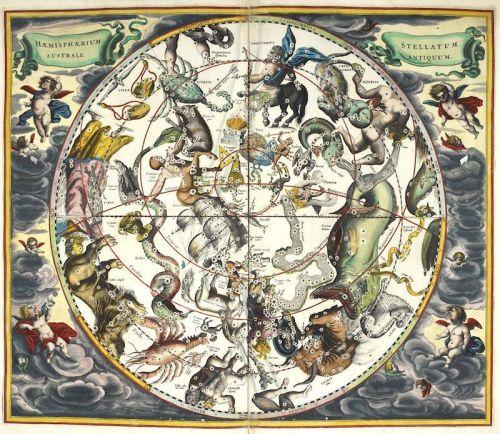

One of the most durable traditions is the grouping of stars; our ancestors have been looking up at the stars and studied their placements for many thousands of years. The constellations used in the west (Europe and America) have their origin in the Greek system of 88 constellations as recorded by Ptolemy ➚. These in turn had their roots in the older Middle East civilizations in Mesopotamia ➚ over 3,000 years ago.

If Chinese civilization had a common ancestral root with Europe and the Middle East it would be expected that Chinese groupings of stars would have something in common. However, this is not the case, the whole approach to designating constellations and the study of astronomy is different. This fact gives strong evidence of cultural independence from ancient times. As early as the end of the Han dynasty over a thousand stars had been cataloged. The familiar charts of dots for stars with joining lines came into use as early as 1000CE in both China and the rest of the world.

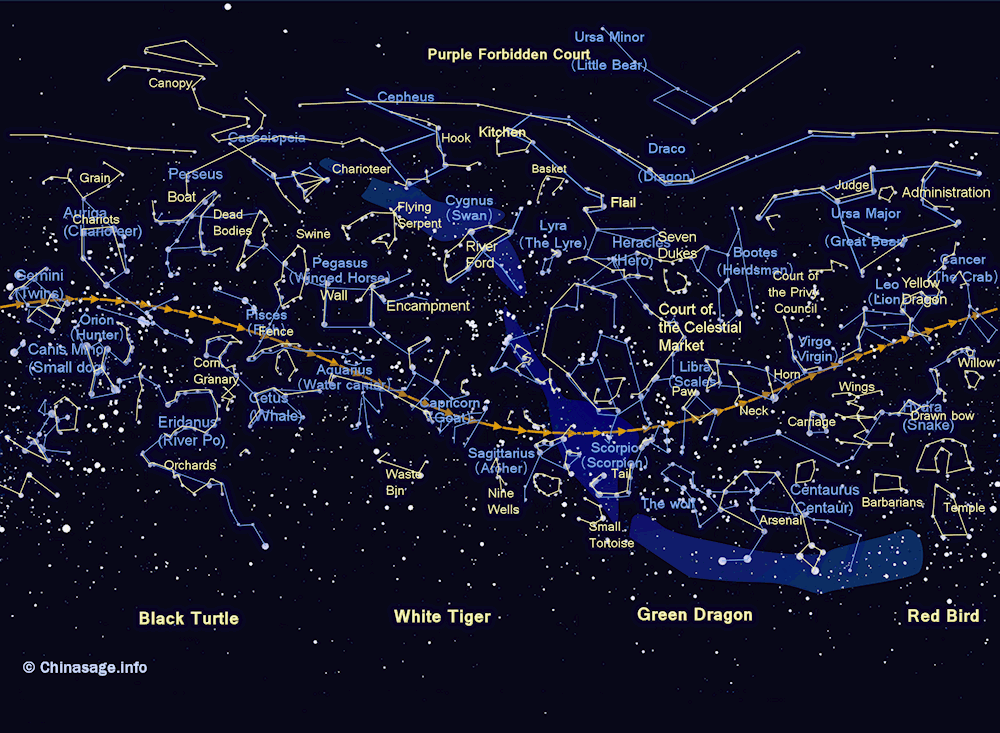

While in the west importance is given to the zodiac, which are the twelve constellations that the sun moves through during the year, the Chinese concentrated on the 28 mansions that mark the movement of the moon during a month. Up until the foundation of modern China the Chinese calendar used a system based on the moon, dividing time into lunar months. This has the practical benefit that you can tell the day of the month by looking at the current location of the moon against the stars. The Western solar zodiac system gives a vague idea of the current month, as you can not see the constellation that the sun is in front of.

Imperial Order

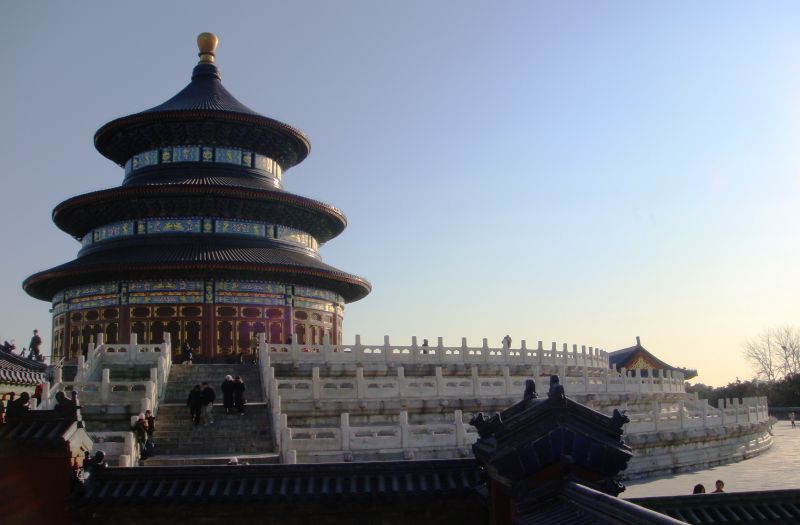

The Western system used Greek legends for naming the constellations, there is no overall organization for the stars, although some constellations have linked origins such as Pegasus, Perseus and Andromeda. By contrast, China developed an impressively consistent scheme. The Emperor is at the north pole, the fixed point around which all other stars revolve. Laid out underneath him is a celestial landscape that broadly reflects the layout of an imagined Imperial court. There are many more Chinese constellations (283) than in the west in smaller groups with fewer stars. The whole sky is viewed as a scene in the heavens to reflect the organization of the Chinese nation on Earth. There are some similarities to the Indian system and it is unclear who developed the system first as it is known to date back a long way at least as far as the Shang dynasty.

Around the Emperor are three enclosures, the Purple Forbidden Enclosure 紫微垣, which includes the pole star, Ursa Minor, Draco, Ursa Major, parts of Bootes and is linked to the Purple Forbidden City at Beijing on Earth. The stars in the enclosure are always visible. The second enclosure, the Supreme Palace Enclosure 太微垣 covers Leo, Virgo, parts of Ursa Major and Coma Berenices. These constellations are visible in spring/early summer in the northern hemisphere. The third is the Heavenly Market Enclosure 天市垣 which covers Ophiuchus, Serpens, Hercules, Corona Borealis and these constellations are visible in late Summer/Fall in the northern hemisphere.

Star maps were made from early days. In 940CE maps using a cylindrical light projection were produced - six hundred years before this idea was ‘discovered’ by Mercator in 1568. In 1093 a star map had 1,565 named stars. The Chinese invented equatorial mountings for their telescopes so that the stars could be followed in their apparent curved orbit around the celestial north pole with a single adjustment.

Chinese Planets

To the Chinese the planets do not hold as much importance as the stars and they are named with the five Chinese elements: Mars with fire 火星 ‘fire star’; Jupiter with wood 木星; Venus with metal 金星; Mercury with water 水星 and Saturn with earth 土星. The apparent color and shape of the planets was used in astrology to predict important events, for example if Saturn appears red then calamity is at hand.

Ancient Observations

It was the famous scientist Laplace [1749-1827] ➚ who said “Of all the ancient peoples, the Chinese have the most ancient records of the science of astronomy”.

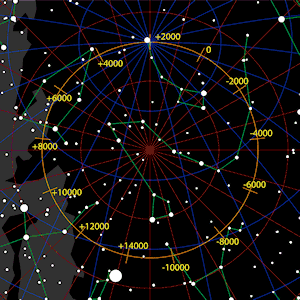

Zu Chongzhi ➚ (429-500 CE) was one of most famous Chinese mathematicians and astronomers. He was the first person to take account of the precession ➚ of the axis of the earth. The axis rotates around a circle every 25,800 years, which works out as one minute of arc every 72 years. The reason for the precession was not understood until Newton's theory of gravity ➚. It occurs because the Earth is not a perfect sphere but bulges slightly at the equator due to its rotation. The tilted axis of the Earth gives a varying gravitational pull by the sun and moon on this bulge and that is what leads to the precession. Early astronomers became aware of this because the position of the apparently stationary northern pole and the solstices changed gradually over hundreds of years. This apparent wandering of the poles over the centuries required accurate measurement to detect these small, slow changes. The star chosen as the ‘pole star’ had to change over time and this can be used to date when Chinese observations were made. The great Chinese scientist Shen Kuo accurately calculated the rate of precession 500 years later.

Predicting Eclipses

Astronomy is of great importance because the accurate prediction of the eclipses of the moon and sun became vital. Ordinary people saw the battle in the heavens between sun and moon as a very ominous threat, if the ruler had prior knowledge of these events he could limit potential unrest. It was of particular importance in China because the Emperor was ‘Son of Heaven’ and the conduit of interaction between earth and sky. An unexpected eclipse would immediately cast a doubt on the ruler's Mandate of Heaven (right to rule). Qing Emperor Qianlong states in his abdication message of 1794 that a forthcoming solar eclipse and a lunar eclipse were both taken as signs that a change of ruler was necessary; but he had also reigned for an impressive 60 years. From early times it became important to track the sun and moon to help predict eclipses and other events, so astronomy was a privileged study permitted to only a few scholars at the Imperial Court. China has kept an unbroken set of astronomical observations longer than any other civilizations.

Setting the calendar

Astronomical observations were also needed to work out the accurate start of each year and month so they could be formally proclaimed in advance - synchronizing everyone's calendars. It is all very complex because the simplistic view of circular orbits in a single plane is inaccurate. The moon's orbit is tilted 5° relative to the Earth's equatorial and is slightly elliptical as well as precessing, so both detailed measurement and complex mathematics are needed to predict its path.

The Chinese concentrated on the pole star and the stars around it because the observed stars are not obscured by the bright sun or moon. Circular jade discs were made with notches filed into it to mark the position of key circumpolar stars so that the north pole and the time could be easily determined - and all this as far back as 1000BCE. This indirect measurement of the position of the sun is far easier to make but more complex to use than the European/Greek measurement of the stars visible just before sunrise and after sunset. The position of the full moon can also be used to determine the position of the sun as at this time it is directly opposite.

Birth stars

There are sixty stars each associated with a year that make up a stellar cycle. The tradition was to venerate the appropriate year star on your birthday and also at Chinese New Year. Many significant stars have legends associated with them - typically they control one particular aspect of life. So there is a Betrothal star; a Rheumatism star; a Peach Blossom star controlling mental illness and so on. In the constellation of Leo are the Five Emperors. The Great Bear is split into two constellations and is the seat of divine justice. The ‘Seven Stars’ in China can refer to sun; moon and the five major planets but also to Ursa Major ➚ (the Northern Dipper or Plow or Great Bear). The Great Bear appears directly overhead at times over parts of China and was therefore considered the center of the heavens and a supreme astral deity. Known as 北斗 Běi dǒu (Northern cup) in China it was represented as a red faced god who determining death and plays chess with the Southern Dipper. The seven stars of the dipper are important in Daoism and are often shown as august figures in pictures who can bring long life and wealth. In the ‘Flying Star’ system of Feng Shui it is these stars that determine good fortune. The Dipper has been used in the west to quickly locate the pole star but the Chinese used other pairs of stars to find it, for example the stars in the constellation of Orion. Knowledge of the stars of the southern hemisphere is known from the Song dynasty well before contacts with western astronomers and strongly suggests trading links with people south of the equator.

Milky Way

The most famous astral tradition is the romance of the Spinning damsel Zhi Nu 织女 and the ox-herd Niu Lang 牛郎 marked on the Double Seventh or Chinese Valentine Festival each year. The story is that the Herdsman constellation (Aquila in the Greek system) and the Weaver girl (Lyra in the Greek system) were kept apart by the Milky Way as punishment for illicit dalliance. The Double Ninth was the one night she could go to meet him by way of a bridge formed by magpies across the silver, starry river 银河 yín hé (the Milky Way). The copious grief at their parting was supposed to cause the heavy rains that often occur at this time of year.

Comets were considered unlucky portents representing tumult in the heavens, as they did in other cultures. The appearance of Halley's comet ➚ in 1910 probably helped the republicans in their overthrow of the Qing dynasty.

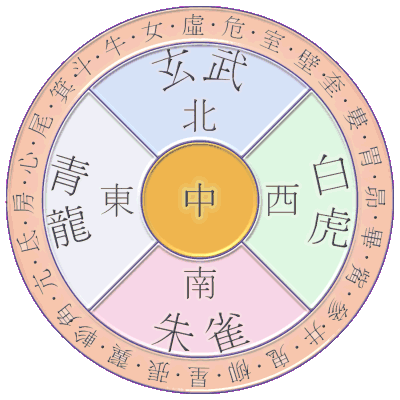

The Chinese Days of the Month or Mansions

There are 28 mansions or (xiu or sù 宿), one for each day of the lunar months which the moon moves through; they are collectively called the 二十八宿 ‘28 constellations’. These served as the names of days of the month before the adoption of the Gregorian calendar. Some say they are named after generals slain by the Emperor Guang Wudi of the Eastern Han dynasty. Co-ordinates of stars were measured relative to the xiu divisions and the distance from the northern stellar pole. These mansions are marked out on the 罗盘 luó pǎn compass used by feng shui practitioners.

The month is divided into four periods 四象 representing the four seven day weeks in a lunar month and also the four seasons. The position of the sun in these mansions can be used to calculate the jieqi calendar of solar terms, which is the important and ancient agricultural calendar.

| Number | Name (pinyin) | Translation; association; element | Greek star |

|---|---|---|---|

Azure (blue) Dragon of the East 东方苍龙 dōng fāng qīng lóng Spring | |||

| 1 | 角 Jiǎo | Horn; Earth dragon; Wood | α Virgo |

| 2 | 亢 Kàng | Neck; Sky dragon; Metal | κ Virgo |

| 3 | 氐 Dǐ | Root; Badger; Earth | α Libra |

| 4 | 房 Fáng | Room; Hare; Sun | π Scorpio |

| 5 | 心 Xīn | Heart; Fox; Moon | σ Scorpio |

| 6 | 尾 Wěi | Tail; Tiger; Fire | μ Scorpio |

| 7 | 箕 Jī | Winnowing basket; Leopard; Water | γ Sagittarius |

Black Tortoise of the North 北方玄武 běi fāng xuán wǔ Winter | |||

| 8 | 斗 Dǒu | Southern dipper; Qilin; Wood | φ Sagittarius |

| 9 | 牛 Niú | Ox; Metal | β Capricorn |

| 10 | 女 Nǚ | Girl; Bat; Earth | ε Aquarius |

| 11 | 虚 Xū | Emptiness; Rat; Sun | β Aquarius |

| 12 | 危 Wēi | Rooftop; Swallow; Moon | α Aquarius |

| 13 | 室 Shì | Encampment; Bear; Fire | α Pegasus |

| 14 | 壁 Bì | Wall; Porcupine; Water | γ Pegasus |

White Tiger of the West 西方白虎 xī fāng bái hǔ Autumn/Fall | |||

| 15 | 奎 Kuí | Legs; Wolf; Wood | η Andromeda |

| 16 | 娄 Lóu | Bond; Dog; Metal | β Aries |

| 17 | 胃 Wèi | Stomach; Pheasant; Earth | 35 Aries |

| 18 | 昴 Mǎo | Hairy head; Cockerel; Sun | 17 Taurus |

| 19 | 毕 Bì | Net; Raven; Moon | ε Taurus |

| 20 | 觜 Zī | Turtle beak; Monkey; Fire | λ Orion |

| 21 | 参 Shēn | Three stars; Ape; Water | ζ Orion |

Vermilion (red) Bird of the South 南方朱雀 nán fāng zhū què Summer | |||

| 22 | 井 Jǐng | Well prop; Tapir; Wood | μ Gemini |

| 23 | 鬼 Guǐ | Ghost; Sheep; Metal | θ Cancer |

| 24 | 柳 Liǔ | Willow; Deer; Earth | δ Hydra |

| 25 | 星 Xīng | Star; Horse; Sun | α Hydra |

| 26 | 张 Zhāng | Extended net; Deer; Moon | υ1 Hydra |

| 27 | 翼 Yì | Wings; Snake; Fire | α Crater |

| 28 | 轸 Zhěn | Chariot; Worm; Water | γ Corvus |