Porcelain and the Ceramics of China

For many centuries China has been pre-eminent in the production of ceramics. Indeed the very name ‘china’ is a term for ceramics, particularly porcelain because for many centuries the country was the only source of quality ceramics.

Invention of Porcelain in China

As with many ancient cultures the production of earthenware vessels from clay goes back a very long way, in the case of China at least 8,000 years. By 3,500BCE distinctive styles and decorations covered amazingly thin ceramic objects as seen in the Yangshao ➚ and Longshan ➚ cultures. The legendary Yellow Emperor Huangdi is credited with personally supervising the imperial kilns. In the Shang dynasty a characteristic green glaze was applied to stoneware pottery in bold swirls and lines. Glazed as well as unglazed 'terracotta' pottery continued into the Han dynasty. A proto-porcelain began to be made in small quantities by the late Han dynasty. The gradual development towards fine, smooth porcelain continued into the Tang dynasty when quartz and feldspar were mixed with the clay; by this time several different colored glazes were available - including the famous 三彩 sān cǎi three color glazes ➚ of normally brown (or amber); green and cream but other combinations of three colors were also used. These finely detailed objects such as horses were often made for decoration, particularly as burial gifts in tombs. They are fired at a lower temperature than porcelain and are fairly brittle.

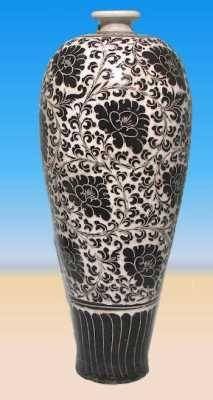

With the rise of Islam in the Song Dynasty there was a large increase in trade by sea from southern Chinese sea ports to Africa and to Japan. Some Islamic motifs made their way into Tang and Song decorations. Zizhou in Hubei was an important center at this time.

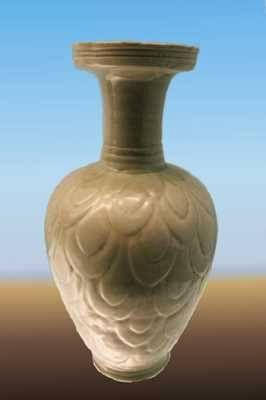

The plain designs of celadon ➚ Song porcelain remain some of the most prized ceramics ever produced. Many have characteristic light green, crackled glazes in simple shapes without decoration. The high price of original celadon wares has encouraged forgers to produce replica vessels that are very difficult to distinguish from the originals. When the center of Chinese culture moved south in the Song, new kilns were built there. The Song period saw further innovation; the careful control of firing temperature and processing of the clay led to many quality creations. The shapes are sober and pure for all kinds of vessel: jugs, bottles, bowls and cups. Some were undecorated while others had simple naturally inspired designs incised. Famous kilns were at Dingzhou, Hebei; Longquan, Zhejiang and Ruzhou, Henan.

The secret of porcelain manufacture

By the time of the Sui dynasty true porcelain had at last been mastered using the kaolin and petuntse found near Jingdezhen, Jiangxi. The fine local clay is fired to a very high temperature to produce thin, translucent but robust porcelain. Petuntse (白墩子 bái dūn zǐ) is a feldspar rich (known as ‘porcelain stone’) that also contains mica, it results from the weathering of granite. Kaolin (’china clay’) is named after the village of 高岭 Gāolǐng near Jingdezhen is a clay mineral, principally aluminum silicate produced from the weathering of feldspar. High quality porcelain is made by equal parts of porcelain stone and china clay, cheaper material is made with a higher proportion of porcelain stone. Potters think of the petuntse as providing the dry bones of the porcelain and the kaolin providing the soft flesh, only together does it provide sufficient rigidity and yet remain flexible enough to be molded into a shape that is preserved in the kiln. The porcelain is fired to a high temperature 2,552 ° F [1,400 ° C] to achieve higher strength than conventional ceramics. This very high temperature of firing chemically alters it into a strong, translucent 'glass'. The porcelain found favor with the Imperial court and it was huge imperial orders for porcelain that led to the expansion of production at Jingdezhen (probably as early as 557CE). At this point manufacture had still used small family run kilns, with specialist techniques kept carefully secret. The separate skills of clay preparation, glaze mixing and decoration developed as separate professions. China clay (kaolin) was mined and mixed with petuntse into a fine powder that was passed through a silk sieve. Water was added to the clay and it was thrown onto a potter's wheel to form a rough shape. Another worker then refined the shape and added detailing. The object was then passed on to a specialist who applied glazes and finally the porcelain was fired for a few days. Sometimes there were multiple applications of glaze and several firings to make the finished piece.

During the Yuan dynasty the Song process of manufacture continued but with a much wider export market to India, Indo-China and Persia with more diverse designs. Islamic designs came into prominence and cobalt blue ➚ from Persia (Iran) added to the range of colored glazes available. However the high level of refinement and innovation of the Song vessels was lost in the succeeding Yuan dynasty when 'blue and white' wares began to predominate.

Potteries in Europe up to the 18th century were unable to produce anything quite so fine and thin as porcelain. China continued to zealously guard the secret of its manufacture - as it did for silk. Some believed porcelain was produced by burying earthenware for fifty years and others that it was made from crushed egg shells. The secret of manufacture was smuggled out by Jesuits and became widely known in 1712 after the publication of 'Lettres édifiantes et curieuses de Chine par des missionnaires jésuites'.

Jingdezhen mass production

Later in Ming dynasty times the kilns at Jingdezhen, Jiangxi for the production of porcelain were further expanded. China's system of rivers and canals was ideally suited to the safe transport of this delicate merchandise. By 1433 over 500,000 pieces were being produced each year in an early example of integrated mass production using specialist craftsmen for the different phases and designs. As many as seventy people could be involved in the production of a single piece. By the Qing dynasty the workforce had grown to 100,000 people. Kilns specialized in creating different styles of porcelain and some craftsmen were expert in particular styles of ornamentation. The secret of the translucent, fine white ‘china’ was a closely guarded secret. The pure white kaolin ➚ clay (china clay) was used in mass production for the imperial court and later on for export to Japan and then to Europe. The famous early ‘blue and white’ glazed wares, of Yuan or Ming dynasty date, achieve high prices at auction today, but many forgeries have been made, as long ago as the late Ming. Indeed it is said only one in ten of pieces marked as Ming actually date to that period. European manufacturers tried hard to copy the sought after properties of porcelain but could only initially produce ‘cream wares’ which were thick white glazes over earthenware bodies. At first Japan was the top export destination for Chinese porcelain, Europeans became involved in the sea trade and then when it became highly prized by the middle and upper classes in Europe the export of porcelain overtook silk as the most valuable Chinese export.

It was in Ming times that the cloisonné ➚ enamel technique was invented. Areas of an object are laid out with fine metal wire which are filled with powdered enamel and fired; this enables objects with a large amount of fine, exquisite detail to be produced with sharp edges between colors.

The name ‘porcelain’ comes from an old Italian name for the polished, glazed surface of cowrie shells (porcellana) that resemble Song celadon wares. Porcelain is called 瓷 cí in China.

Canton Porcelain export

The secret of porcelain was kept from foreigners by only allowing trade in the precious cargo at Guangzhou (then known as Canton) far away from where the craftsmen made it. All the millions of items were carried south by boat along the Gan River, Jiangxi and then by foot over the mountains down to the Pearl River and then finally by river boat to the port of Guangzhou. Once the secret of porcelain was discovered, European manufacturers were able to make it from kaolin deposits elsewhere in the world, for example at St. Austell in Cornwall ➚.

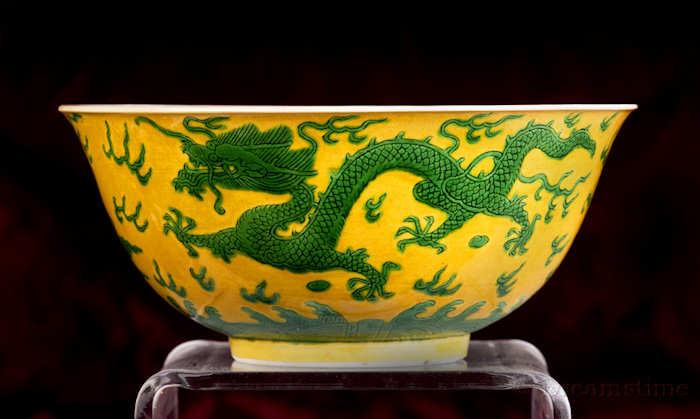

From Ming into Qing times the range of colors increased and the majority of production was geared to export - increasingly to Europe. Famille Rose porcelain ➚ was made - the palette of colors was enhanced with colloidal gold to give a soft rose color in the late Ming dynasty. In the Qing Five color 五彩 wǔ cǎi palette of colors came into prominence to be followed by the greenish Famille Verte palette. Designs reflected european tastes, often specifically commissioned, rather than using traditional Chinese motifs. Porcelain was produced with european scenes, european people and wildlife in the landscapes. Although technically the porcelain became progressively more refined and better made, the creativity of shapes and motifs went into decline. This was partly due to the imposition of central control over production from Beijing which stifled individual creativity. Pieces became larger and garishly colored and over-ornamented.

As well as fine, smooth porcelain, China has continued to produce unglazed earthenware vessels. Centered around places such as Yixing, Jiangsu where high quality clay is found, potteries developed their individual characteristics particular the famous their red and purple teapots ➚ which are said to enhance the flavor of the tea (they have a fairly rough surface that absorbs some of the flavor). These have been made since the Song dynasty and became very popular in Japan where they are known as 'temmoku ➚'