The Ming tombs of Beijing

The magnificent burial tombs of the Ming dynasty emperors are located 28 miles [45 kms] north west of Beijing. Just like the Egyptian pharaohs the Chinese emperors took great care to build and furnish lavish tombs for their after-life. The Ming tombs are very impressive but not quite on the scale of Qin Shihuangdi's tomb near Xian with its thousands of Terracotta warriors.

Many visitors do not have sufficient time to give the Ming tombs a complete visit and come away a little disappointed. To get a true impression of the grandeur and scale of the tombs requires a full day of precious sight-seeing time, as you really need to start with the Sacred Way then the Changling tomb and finally the Dongling tomb.

Ming Emperor Yongle after fighting a civil war for the right to succeed Emperor Hongwu moved the whole Imperial capital with all its administrators from Nanjing north to Beijing. He wanted a tomb complex for his heirs and successors close by and so after careful consultation with Feng Shui practitioners the site at Changping was chosen. There has always been a tradition of family tombs rather than individual graves in China, the Ming tombs are the premier example of this attitude to ancestors. In Chinese they are called 明十三陵 Míng shí sān líng literally the Thirteen Ming tombs.

The valley of the tombs

The Ming dynasty was the first to build a necropolis near Beijing. The tombs are spread out over 17 sq miles [44 sq kms] (12 times the size of New York's Central Park) and so visitors need considerable time and motorized transport to see them all. It is not all contained within a park there are now towns and villages within the vast tomb complex area.

The tombs are located in a valley enclosed by a semi-circular range of hills and faces south with a stream running west to east across the middle to conform with the very best auspicious burial location according to Feng Shui. The tombs are built into valley sides rather like the Valley of the Kings ➚ in Egypt. All the main 13 tombs as well as many more minor ones were reached from a single road - the Sacred or Spirit Way. The whole area was surrounded by a large red wall and it was forbidden (except for the sentries) for anyone to enter, or even less collect wood or stones within the whole valley. The walls had many towers dotted along it, unfortunately these have all now been lost.

There is not much to see above ground as the tombs are spread out over such a large area which has now been developed for agricultural, industrial and domestic use. The main visitor site is at just one of the tombs - the Dingling tomb of Emperor Wanli and located here is the popular Ming Tomb museum 明十三陵博物馆 Míng shí sān líng bó wù guǎn.

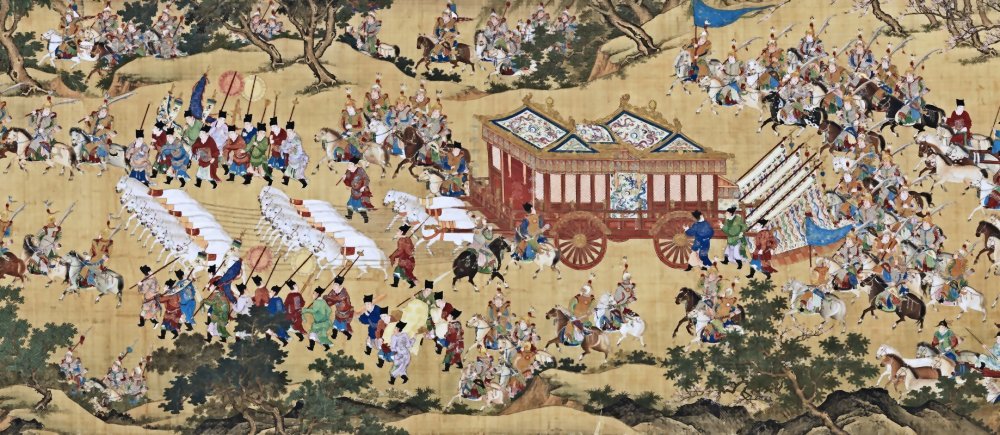

After death in Beijing the body of the emperor was taken out of the north gate of the Forbidden City and waited at 寿皇殿 Shòu Huáng Diàn near Coal Hill until the auspicious time for burial. The body would, on the carefully chosen day, be carried to the tombs along the Sacred Way with a huge procession and great ceremony. As well as at the Ming tomb complex, the Emperors are commemorated in central Beijing at the 历代帝王庙 Lì dài dì wáng miào Temple which is dedicated to the 188 Emperors ➚ of every dynasty.

Sacred or Spirit Way 神道 shén dào

The start of the long road to the tombs begins near the village of Changping which is where the road from Beijing branches off from the route to visit the Great Wall at Badaling (S216) north towards the tombs (S212). Changping was the headquarters of the garrison charged with guarding the tombs. The Sacred Way is 2 miles [3 kms] long and is now within the outskirts of Beijing. Nowadays it has busy roads running on either side of it. It is much less visited than the tombs themselves which are 2 miles [3 kms] further on. All the dynastic tomb complexes had a Spirit Way, we have a separate section all about these; the Ming tombs have the best preserved example of a sacred or spirirt way.

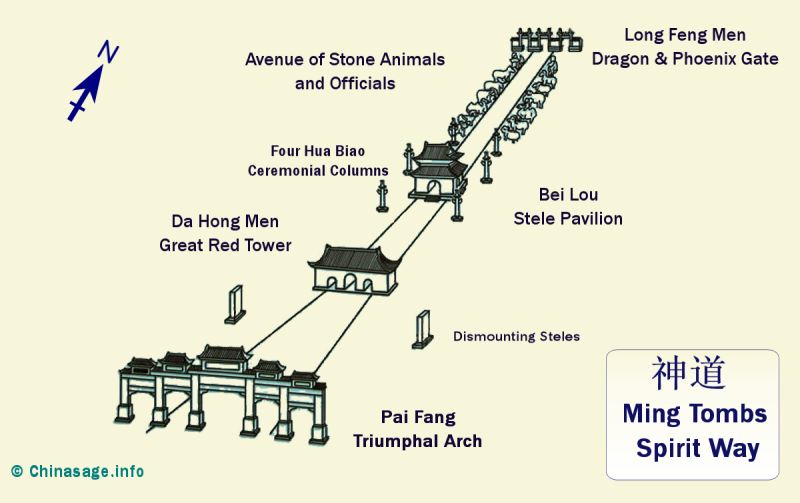

A schematic map of the layout of the Ming Tombs Sacred (or Spirit) Way at Changping.

On the right-hand side of the valley entrance is Dragon Mountain 龙山 lóng shān on the left-hand side is Tiger Mountain 虎山 hǔ shān. So it is guarded by the most auspicious animals the dragon and tiger.

Triumphal Arch

The Sacred Way begins with a marble Triumphal Arch 牌坊 Pái fāng erected in 1540, the dedication plaque is left deliberately blank as it was forbidden to write the Imperial dynastic name. It is the largest marble built paifang or dolmen in China and has eleven towers, six pillars and five arches. The pillars are linked by double lintels each of which is a single slab of stone. The roof of the paifang is in the form of traditional roof tiles but made of marble. The arch is not much visited and quite hard to find, it is slightly off the line from the main way.

Entrance Gate

The ‘Great Red Gate’大红门 Dà hóng mén is the real start of the Spirit Way and is in the form of a 牌楼 Pái lou. The gate was the only opening in the encircling red wall and is sited at the valley entrance. It is an impressive construction with three arches each 120 feet high and 35 feet across with bright red walls. It originally had wooden doors with the central door only ever opened for the Emperor's coffin to pass through. Even living emperors had to use the side doors. This are two larges steles on the other side of the gate that orders everyone to dismount 官员人等至此下马 guān yuán rén děng zhì cǐ xià mǎ officials and others must dismount. Only royals could ride onwards to the tombs.

Stele Pavilion

The next construction along the way to the Ming Tombs is the Stele Pavilion 碑楼 Bēi lóu 500 yards [457 meters] further on. Originally this had a double roof supported by 12 immense wooden pillars 30 feet [9 meters] high. It was erected in 1426 and it houses a huge stone stele mounted in back of a type of tortoise (a Bixi 赑屃) 50 tons [45,359 kgs] in weight. It is probably the largest stele in China. Inscriptions on the stone include those by Emperor Hongxi (the 4th Ming Emperor) and Qing Emperor Qianlong (see separate section all about steles).

There are four 华表 Huá biǎo (ornamental and spiritual columns) at each corner that are made of white marble. Each Huabiao is inscribed with 41 dragons. On top of each of the columns is a sculpture of a mythical creature facing outward.

Avenue of Animals

An avenue of animal statues begins 300 yards further on. The first sculptures are hexagonal columns with a cloud design on the top of a rounded cylindrical shape. A set of animals along the Spirit Way was a feature of tombs from the Han dynasty onwards. They were erected in the 15th century and are evenly spaced out 144 feet [44 meters] apart.

The stone statues, carved from a single huge stone are in order: kneeling lion, standing lion, kneeling xiezhi mythical beast, standing xiezhi, kneeling camel , standing camel, kneeling elephant , standing elephant, kneeling qilin mythical beast, standing qilin, kneeling horse, standing horse. There are 12 animal statues on each side. The vastness of the Ming Empire is made clear by the choice of animal: camel for west, elephant for south and horse for north. The kneeling figures are presumed to be resting in readiness to replace the standing figures in rotation. The legend is that the statues would come to life to protect the Ming tombs.

Avenue of Officials

The Spirit Way then turns slightly east (according to ancient rules of Feng Shui) and the statues of humans begin. Only Emperors or ‘kings’ could have human statues in their Spirit Way. On each side there are two military mandarins or generals (武臣 Wǔ chén) wearing sabers then two civilian mandarins (文臣 Wén chén) and then finally two meritorious, venerable mandarins (勋臣 Xūn chén).

Dragon and Phoenix Gate

The end of the line of stone statues is marked by the 龙凤门 Lóng fèng mén ‘Dragon and Phoenix Gate’. The dragon represents the Emperor and the phoenix the Empress. It has three openings with the way running also on each side. This is the end of the Sacred Way into the Ming tomb complex, the route now becomes a modern road with villages and orchards between this point and the actual tombs scattered around the valley still 2 miles [3 kms] further north.

Ming Tomb Complex

The large valley has the 13 emperor's tombs. It used to be uninhabited and heavily guarded up until the end of the Imperial Era in 1924 - a place of quiet solitude. To complete the auspicious Feng Shui there is a stream running from the west to east. This stream is now the source a reservoir named the ‘Ming Tombs reservoir ➚’ built in 1958 to supply water for Beijing. Chairman Mao himself joined the work party and it took six months to complete. There is a modern seven arch bridge over the stream replacing the original one.

Some damage was done to the tomb complex in the rebellion of Li Zicheng in 1644 and this was followed by raids by the Manchus on founding their new dynasty in 1644/45. The Manchu leader Dorgon ordered their destruction and the Dongling tomb bore the brunt. The tomb buildings took two months to burn down. At Changling only Yongle's Great Hall was left standing.

However the Qing dynasty then chose to honor the Ming emperors and the last Ming Emperor Chongzhen was buried here at Si ling following the Ming tradition. Some of the destroyed buildings were rebuilt but on a smaller scale. This was probably to assuage the anger of Ming loyalists who mounted a fierce rebellion in southern China up until 1683. In 1725 Qing Emperor Yongzheng made a descendent of the Ming Imperial line a marquis and responsible for maintaining the rituals at the tombs. All the Qing Emperors then continued annual ritual sacrifices to the Ming Emperors at the complex right up until the Last Emperor Puyi when he left China in 1924.

Only two tombs attract the bulk of the visitors. Changling has been restored but his burial mound has not been excavated. Dingling has been restored and excavated. It is likely that all the Imperial Ming tombs have the same layout and contents as Dingling because the rules for burial rites were very closely circumscribed. Apart from emperors and their empresses, there are an area of tombs for seven concubines along the western fringe and one for top eunuchs who are buried here, but with much smaller monuments. Emperor Wanli preferred concubine Zheng ➚ over his Empress and sought to make her son as his heir. She is the most famous consort buried at the tomb of the concubines.

General Ming tomb design

Each of the tombs follows the same design pattern and is made up of three parts. A sacrificial building Lingen Hall 祾恩殿遗址 líng ēn diàn yí zhǐ ‘Hall of Eminent Favors’, a Spirit Tower 石五供 shí wǔ gòng containing a stele that lists the deceased achievements. The final third part is a round burial mound (tumulus) under which is the burial chamber. The symbolism is that heaven is round while earth is square. Not all the tombs retain the buildings above ground, usually all that can be seen is the round tumulus which is encircled by a stone wall the 宝城 Bǎo chéng.

The burial chambers underground are laid out the same way as the palaces of the living with luxuries ready for use in the after-life. The tombs are key shaped - rectangular buildings facing roughly south link to a round burial mound against the valley side surrounded by a stone wall. The mound is usually planted with trees. As well as being decorative, the tree roots would make it hard for tomb raiders to dig down into the mound. The junction between the two parts is at the Spirit Tower.

The sacrificial buildings include a burner 焚帛炉 Fén bó lú to burn messages written on silk strips to send to the ancestors. All the buildings of the complex have red walls and yellow roofs to denote their Imperial status.

The Thirteen Ming Tombs

Here is the list of the 13 tombs giving the name of the tomb, the emperor, dates of birth and death together with the dates of his reign (r.). 陵 Líng means ‘tomb’. They are listed in order of their construction:

- Chang Ling (1424) 長陵 Emperor Yongle (1360-1424 r. 1403-24). One of the two fully restored tombs above ground but the burial chamber has not been excavated. There are 16 concubines buried with him .

- Xian Ling (1425) 献陵 Emperor Hongxi (1378-1425 r. 1425) 10 concubines buried with him.

- Jing Ling (1435) 景陵 Emperor Xuande (1399-1435 r. 1426-35) 10 concubines immolated with him.

- Yu Ling (1449) 裕陵 Emperor Zhengtong/Tuanshun (1427-64 r. 1436 and 1457-64)

- Mao Ling (1487) 茂陵 Emperor Chenghua (1447-87 r. 1465-87)

- Tai Ling (1505) 泰陵 Emperor Hongzhi (1470-1505 r. 1488-1505)

- Kang Ling (1521) 康陵 Emperor Zhengde (1491-1521 r. 1506-21)

- Yong Ling (1566) 永陵 Emperor Jianjing (1507-67 r. 1522-67)

- Zhao Ling (1572) 昭陵 Emperor Longqing (1537-72 r. 1567-1572).

- Ding Ling (1620) 慶陵 Emperor Wanli (1563-1620, r. 1573-1620). His tomb has been restored and his is the only burial chamber that has been excavated.

- Qing Ling (1620) 定陵 Emperor Taichang (1582-1620 r.1620)

- De Ling (1627) 徳陵 Emperor Tianqi (1605-27 r. 1621-1627)

- Si Ling (1644) 思陵 Emperor Chongzhen (1611-44 r.1628-44)

Nine of the tombs were restored above ground beginning in 2002 but only Changling, Dingling and Zhaoling are open to the public

Missing Ming Tombs

There were actually 16 Ming Emperors so there are three that do not have a burial at Changping, these are:- Emperor Hongwu (1328-98 r. 1368-98) The founder of the Ming dynasty used Nanjing as the Imperial capital and he is buried there at the Xiaoling ➚ tomb complex. It is broadly of the same design as Changping but on not so grand a scale.

- Emperor Jianwen (1377-1402?) Jianwen was Hongwu's grandson and chosen successor but was opposed by the future Emperor Yongle and a civil war for succession broke out. The fate of Emperor Jianwen is unknown. Yongle sent out search parties to check whether he had sought exile in a foreign land. He may instead have become a Buddhist monk to evade his uncle. In any case his date of death and burial place are unknown.

- Emperor Jingtai ➚ (1428-57 r. 1450-7) is buried near the Western Hills not the Ming Tombs; the reason for this denial of burial rights is a sad tale. Jingtai's elder brother Zhengtong became emperor in 1436 but he was captured by the Mongol leader Esen Khan ➚ and held captive. Jingtai assumed the mantle as emperor but when Zhengtong was released he refused to give up rule to his brother, instead Jingtai held him prisoner for over six years. Jingtai left no male heir when he died and so it was Zhengtong's son who became the next Emperor Chenghua ➚. Not surprisingly Chenghua did not honor the life of the uncle who had imprisoned him so he gave him a modest non-Imperial burial tomb at the Western Hills ➚.

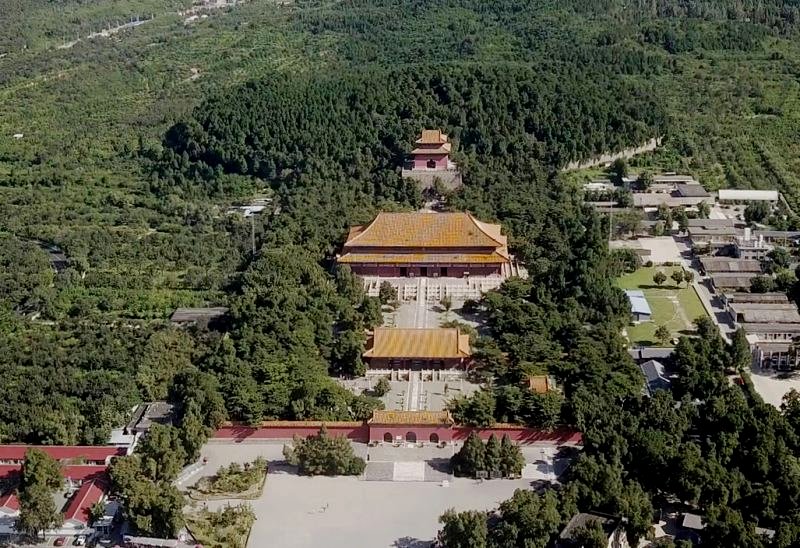

Changling tomb of Emperor Yongle

The first and largest tomb to be built was for the Emperor who built the whole complex: Emperor Yongle (1360-1424, r.1403-24) and Empress Renxiaowen ➚ (1362-1407) who moved the Imperial capital to Beijing and built the Forbidden City. He designed it to be the greatest ever Chinese necropolis. He chose the best Feng Shui position for his first tomb in the complex – it is located under the highest mountain in the valley 大峪山 Dà yù shān on its northern side.

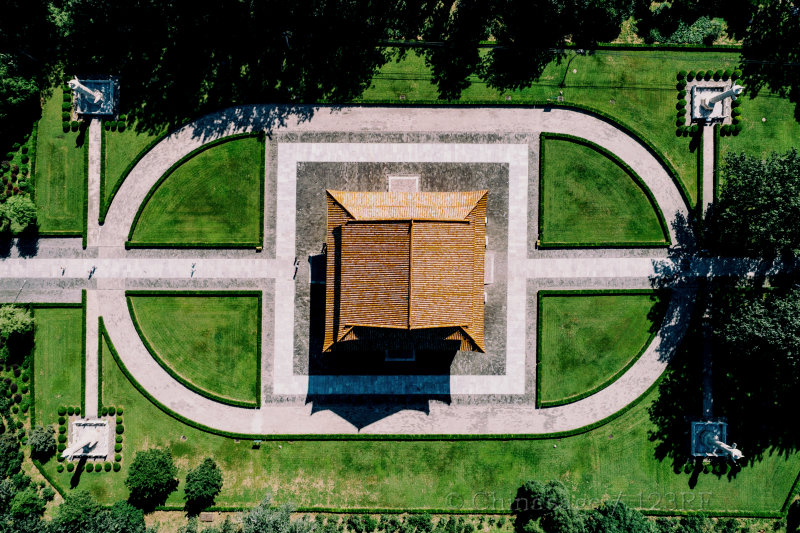

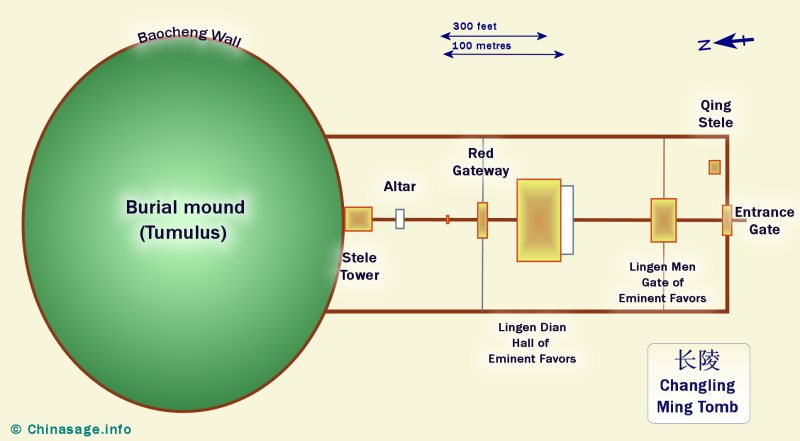

The layout of the Changling Ming tomb as seen from above.

Cháng líng 长陵 Ming tomb has the best preserved tomb buildings above ground (restored in 1950), the underground burials probably remain undisturbed. It begins with a three arch gate that leads to the first courtyard 150 yards [137 meters] long.

In the south-east part of the first courtyard there is a stele erected with the carving of dragons and tortoise which is 27 feet [8 meters] high. It has an inscription by Ming Emperor Renzong ➚ amounting to around 3,000 characters. On the other side there is a poem by Qing Emperor Gaozong. There are also inscriptions by Qing Emperor Qianlong who rebuilt the halls.

Lingen Dian Hall

The Lingen Hall 祾恩殿遗址 líng ēn diàn yí zhǐ (Gate of Eminent Favors) was built in 1586. It was the place to hold sacrificial ceremonies and to enshrine and worship the memorial tablets, hats and clothes of the dead. It was originally built in a magnificent scale: seven bays long and five bays wide, with double eaves. In 1644 it was burned down during Li Zicheng's rebellion. Later, Dorgon, (Prince Rui) broke through the Shanhaiguan Pass and demolished it. In 1785 Emperor Qianlong began reconstructing the hall but at a smaller scale: five bays long and three bays wide. It is 220 feet [67 meters] long and 105 feet [32 meters]wide. It is the second largest Imperial building, only the Hall of Supreme Harmony at the Forbidden City is larger.

In front there is a triple terrace of white marble with balustrades. Sacrifices to all the Ming emperors were made in this hall up until 1924.

The main hall has a double roof of yellow glazed tiles supported by 32 nanmu conifer wooden pillars (each 3 feet [1 m] diameter , 43 feet [13 meters] high) linked by horizontal beams. Nanmu ➚ is a particularly tough and heavy wood that came all the way from Sichuan 621 miles [1,000 kms] away. The lower roof is supported by 28 smaller pillars (each 2 feet [1 m] diameter). The front facade has windows and double doors. In front of the north wall is a Screen or Spirit Wall. The funeral tablet used to be on a wooden altar at the center of hall.

Next there is a three arched gate to a third courtyard 300 feet [91 meters] long to the base of the Square tower.

20 yards [18 meters] on there is a stone portico. In the middle of the courtyard another 40 yards [37 meters] further on is an altar with stone replicas of five sacrificial instruments 石五供 Shí wǔ gòng: a burner, two candlesticks and two vases on an altar. There are then three flights of stairs with the central one carvings of dragon and phoenix. Four stoves covered in porcelain were used to burn offerings stand in front of the steps. There are also three flights of stairs on the north side.

The complex above ground ends with a massive stone tower 23 yards [21 meters] from the altar. A Stele tower on top of it contains a 7 feet [2 meters] stele which bears the inscription 大明 Dà míng ‘Great Ming’ at the top then ‘Tomb of Chengzu’ in the middle. The terrace links to the top of Bao cheng ‘Precious wall’ the boundary of the burial mound that has never been excavated.

Zhaoling tomb of Emperor Longqing

This Ming tomb has been restored and is similar to Changling but on a more modest scale. It receives fewer visitors.

Dingling tomb

定陵 Dìng líng ‘Tomb of Stability’ is the tomb of Ming Emperor Wanli (r. 1573-1620). The Emperor's personal name was 朱翊钧 Zhū yì jūn and his temple name is 神宗 (Shen zong). The building of the tomb began in November 1584 when he was only 22 years old and took until June 1590 to complete. It covers an area of 1,937,520 sq feet [180,000 sq meters]. The budget for the tomb was 8,000,000 taels of silver (a tael weighed about 1 oz [40 grams]). Around 400,000 troops and civilians worked on it.

He is buried with his two empresses 李靖后 Lǐ jìng hòu Dowager Empress Xiaojing 1565-1611 and 李端后 Lǐ duān hòu Empress Xiaoduan 1565-1620 (r. 1577-1620). Dowager Empress Xiaojing was actually a concubine but as her son became Emperor Taichang she was raised to Imperial status.

Dingling is the only Imperial Ming tomb to have been excavated. This was carried in 1955-58 and the burials were found to be undisturbed. Many of the grave goods (or replicas of them) can be seen in a museum above ground. Compared to ancient Egyptian tombs the contents were not numerous. According to Chinese tradition the tombs are laid out for the use of the dead with clothes and has everyday objects rather than immensely valuable items. In addition the walls and ceilings are bare rather than richly painted.

The tomb lies beyond a small bridge, a blank stele leads to a great entrance gate into the first courtyard 重门 zhòng mén. The buildings above ground have been demolished and only foundations remain (you can visit Changling to see how these would have looked). The first courtyard had anterooms for preparing the sacrifices and had steps onto a terrace where the main hall used to stand. The entrance to the next courtyard begins with 棂星门 Líng xīng mén the ruins of a Lingen Hall which was destroyed and only the trace of its layout remain. In the middle of the third courtyard is the 石五供 shí wǔ gòng ‘Five Stone Sacrificial Vessels’ which are an incense burner, two candlesticks and two vases all on top of a sacrificial altar.

The third courtyard now has the main museum. In one room are articles from the Emperor's burial goods and another has those of the two Empresses. Visitors are advised to visit the underground tombs first and the museum on their way back. At the end of third courtyard stands the remains of the Square Tower 方城 Fāng chéng that survived the destruction. This is surmounted by the Stele tower 铭楼 Míng lóu. The stele bears the inscription: 神宗显皇帝之陵 Shén zōng xiǎn huáng dì zhī líng ‘Tomb of the Emperor Shenzong’.

The tower abuts the encircling wall of the burial mound 宝城 bǎo chéng ‘precious wall’. Only the Yongling and Dingling tombs retain their stone external walls . The mound is 755 feet [230 meters] in diameter. Entrance to the 玄宫 Xuán gōng underground palace is nearby.

Within the tomb complex are ancient cypresses which are traditionally planted near graveyards. The deer horn cypress 鹿角柏 lù jiǎo bǎi is believed to be older than the tomb (about 600 years old) and it must have been moved while already a mature tree.

The Underground complex at Dingling

The formal entrance is from the Square Tower but the archaeologists excavating the tomb entered using a special hidden tunnel after the main chamber doors had been sealed. The archaeologists noticed a slight slump in the stone wall which turned out to be the entrance to a tunnel 隧道门 suì dào mén. Following the tunnel they were fortunate to find a stone engraved with precise directions on where to find the main entrance to the tomb.

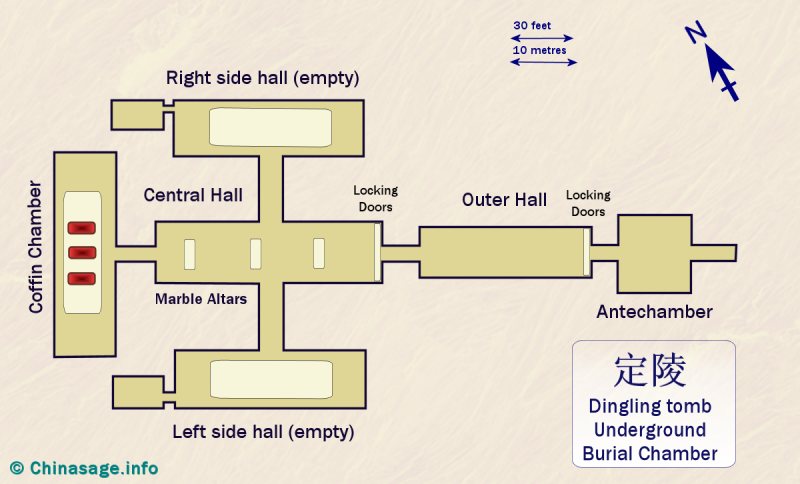

The layout of the underground burial chambers of the Dingling Ming tomb as seen from above.

The main entrance leads down a flight of steps to a depth of 89 feet [27 meters] below the surface. The whole underground area is about 12,863 sq feet [1,195 sq meters] and all the chambers have arched roofs and no supporting pillars.

The first antechamber 金刚墙 jīn gāng qiáng has a Diamond wall which is triangular at the top. The chamber is empty with bare stone walls.

Then there is a double-doored marble gateway of huge stones. Each stone door weighs 4 tons [4,000 kgs] and measures 11 feet [4 meters] high and 6 feet [2 meters] wide. These two doors use a locking mechanism so that when closed they drop down into a wide groove that locks the stones in place so that they could not be opened again so that tomb raiders could not get in. The great doors have lions heads in bass relief 前室石门 qián shì shí mén nine rows of nine heads on each side like Forbidden City doors (nine is the Imperial number). After the antechamber comes the ‘Outer Hall’ which is again protected by self-locking doors leading to the main chamber.

The archway of the main chamber is carved in white marble to resemble a traditional stone and wooden archway complete with tiles. The main central hall is the ‘Sacrificial Chamber’ which has three marble thrones (the central one for the emperor carved with dragons and one for each of his two wives carved with phoenixes). The empresses' thrones used to be aligned to the side walls but have been moved to the center. In front of the thrones were altar pieces for making sacrifices to the deceased. There is also a large porcelain jar containing a wick and oil that was intended to provide an everlasting light for the chamber ‘the thousand year lamp’. It would have soon have extinguished due to lack of oxygen but the burning away of the oxygen helped preserve the fine fabrics that rapidly deteriorated when they were exposed to air and light when the tomb was opened.

The ‘Coffin Chamber’ which lies beyond the main chamber is 98 feet [30 meters] long and 30 feet [9 meters] wide with the roof 31 feet [10 meters] high. It has a stone dais 18 inches [46 cms] high in the middle. It contains modern copies of the original coffins. 26 chests of goods were found here and also a double stone slab bound in iron. The central emperor's coffin of red lacquered wood is between those of the empresses. These are in fact double coffins with one coffin encased within another. Between the coffins were various ceremonial grave goods: an Imperial seal, an iron helmet decorated with gold, a suit of mail, a sword, a bow and arrows. 26 wooden ‘nanmu’ wooden chests containing wooden figurines 木偶 mù ǒu, golden Empress's headdresses, jade belts, shoes and gold chopsticks.

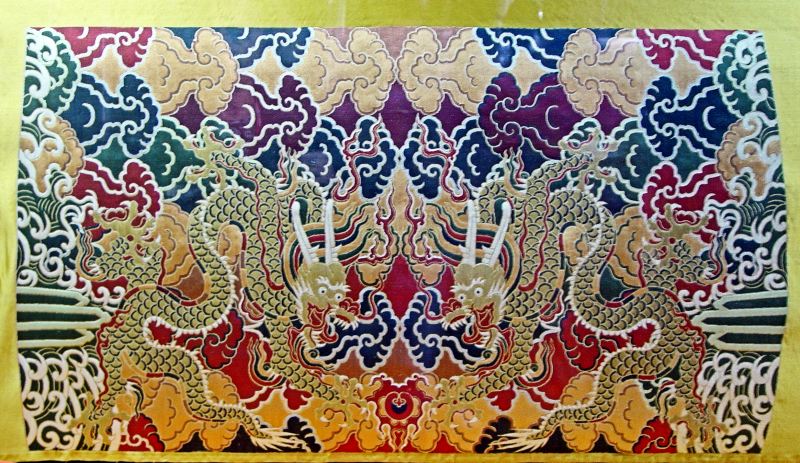

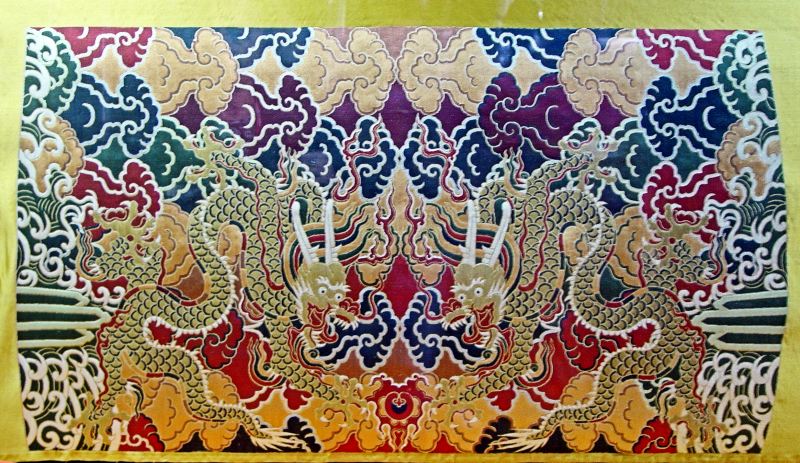

The emperor's body was wrapped in a silk shroud ‘Dragon robe’ with a jade cup and bowl. The most precious find was his fine golden mesh crown with two side wings. Nearby there were 200 bolts of the very finest decorated silk cloth; these are probably the most impressive finds. Unfortunately the original silk quickly decayed once the tomb was opened.

The empress's coffins contained phoenix headdresses, bronze mirrors, cosmetics and toiletries. They wore small golden mesh coronets adorned with many pearls and gems. Empress Xiaojing was wearing a yellow satin jacket embroidered with gold showing one hundred boys at play.

Underneath the bodies were piles of paper money, gold and silver ingots 金锭 jīn dìng for the dead to pay their way in the afterlife. Surrounding the coffins are also large blocks of unpolished jade. Most of the grave goods are now displayed in the Dingling museum above ground, others are replicas as the real items were moved to a Beijing museum for safety.

Connected to the main ‘Central Hall’ of the Ming tomb are passages to two identical and empty chambers. The Left and Right Halls (左配殿 Zuǒ pèi diàn and 右配殿 Yòu pèi diàn). They were constructed but never used for burials. It is thought these were intended for the burial of the empresses if they had survived him. Their later burial would then not require any disturbance of the Emperor's burial chamber but as they actually died before him they were not needed. Another theory is that it was found when burying the empresses that their coffins were too large to fit the narrow passageway to the side chambers so instead they were then placed alongside the emperor.

The Curse of the Emperors?

Kings and emperors do not want their graves disturbed. There are many stories about the Curse of King Tutankhamen ➚ and how misfortune hit Howard Carter ➚'s archaeological team in the 1920s. In the case of the excavation of Emperor Wanli's Dingling tomb the misfortunes that fell are equally curious.

The person who pushed hardest for the 1950s excavation was Beijing's deputy mayor Wu Han ➚ backed by Guo Moruo ➚. The dig was led by Professor Xia Nai ➚ and Zhao Qichang ➚. There was considerable local opposition as all sorts of superstitions prevail around disturbing burials. This was reinforced when lightning struck some of the excavators. Was this like Howard Carter's tomb curse? Opening the tombs produced a curious black mist which terrified some of the excavators.

The excavation was only six years before the Cultural Revolution in China. Soon any admiration for anything ancient or old was a reason for persecution. The feudal, dynastic system was despised and even the Great Wall was physically attacked and damaged in places.

So the archeological dig of Emperor Wan Li's tomb became unacceptable. The excavators fell victim to Mao's purges of intellectuals and their research only surfaced 25 years later in 1989. A good number of finds were taken out and burned as despicable reminders of a bygone age of oppression. The fine wooden coffins were just cast aside and picked up by local villagers. Two children played with one of the coffins and became trapped inside, both suffocating to death.

During the Cultural Revolution Red Guards took the three excavated Imperial skeletons and burned them crying ‘Down with Wan Li, chieftain of the landlord class’ along with a lot of wooden burial goods. Deputy mayor Wu Han who instigated the excavation was killed in 1969 after public humiliation in front of Red Guards. Professor Xia Nai was persecuted and also suffered public humiliation and was sent to a hard labor camp. The current government policy is not to excavate any more of the Ming tombs unless they are threatened with imminent destruction. It certainly does seem that the curse of Emperor Wan Li did fall on those who came to disturb his peace.