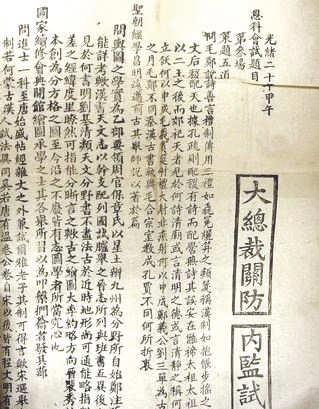

2,000 years of Chinese Examinations

The Imperial examination system of China goes back over two thousand years and its influence pervades Chinese cultural values to this day. In dynastic China the path to wealth and an easy life was through appointment to a well paid government post as a civil service official. The posts were open to any who could pass the daunting examinations. China was the first nation to appoint on academic results rather than patronage. Education has been taken very seriously for a very long time and Chinese children are known for their hard work and success at school work. These current attitudes have their roots in the ancient examination system where success held such great importance. Even when a successful candidate was not given a job in administration, he would be held in great esteem by his community and he would be consulted to give advice on all sorts of matters. When news of the examination system reached Europe via the Jesuits, the system was copied, no longer were administrative positions given on the basis of who you know but on what you know. The underlying principle was a philosophical and ethical one, that virtue is not innate but can be taught and learned.

Image available under a Creative Commons license ➚

Lifelong Learning

The chief difference to modern education is that examinations did not follow a rigorous age-related path culminating in a final University examination in their early twenties. Some candidates repeatedly presented themselves for examination throughout their lives. This was not considered odd or exceptional. The greatly admired Liang Hao of the Song dynasty eventually passed the exams at the age of 84 (as mentioned in the Three Character Classic). It was not uncommon for a grandfather, father and son all to take the same examination together. In 1889 there were 35 candidates over 80 years old and 18 over 90 years old - all from just the one province of Anhui. If someone took the examinations throughout their adult lives but always failed they were awarded the degree at the age of 80 and if a scholar was still living sixty years after graduation the Emperor would pay for a feast in his honor.

Senior officials studied the examination questions that had been set each year and acted as patrons and mentors for bright candidates with whom they were acquainted. In this way, study among the scholarly, was a life-long passion and a constant source of news and debate. China has had a long culture of putting education and examinations as the top priority for life.

First Imperial Examinations

The origins of the open Chinese examination system (Kējǔ or 科举 in Chinese) are in the early Han dynasty when wise rulers figured out that the way to avoid officials building power bases from their family and friends was to appoint on basis of talent. Long before this Confucius had himself set this pattern by taking on students (disciples) on the basis of intellectual merit and not on wealth or family ancestry. In 165BCE Emperor Wendi introduced a system of examinations testing the knowledge of the Five Confucian classics. The Grand Academy 太学 Tài xué was founded in 124BCE. The Four Books and Five Classics (Book of Documents, Book of Songs, Book of Changes, Book of Rites and Book of Ceremonies) were the core texts. Candidates would also be set a question on current affairs. Later stress on agriculture and ethics were incorporated into the system and the 明经 Míng jīng (Expertise in Classics) grade was introduced. In the Han dynasty a candidate was expected to faithfully memorize a text of 3,000 characters.

Reforms

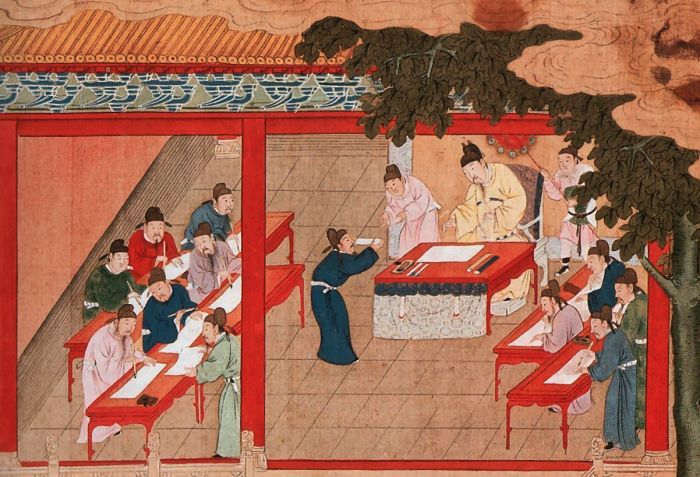

During the Sui, and Tang dynasties and again in the Song dynasty the examination system was strengthened and systematized however in periods of disunity the examination system fell into abeyance. The system only really became a significant institution under the Tang and Song dynasties, previously it had been used sporadically and only for about 5% of top appointments. Its administration then became one of the four principal directorates. By the end of the Song dynasty as many as 400,000 candidates took the examinations, but only about 1 in 300 passed; and only those who succeeded could expect a lucrative post in central government. Each province had to put forward at least three candidates for office each year. Written examinations were used to select 秀才 Xiù cai ‘Flowering talent’ scholars roughly equivalent to a bachelor's degree. Tang Emperor Taizong introduced the 举人 Jǔ rén ‘Raised man’ grade, roughly equivalent to a master's degree. The third level was the 进士 Jìn shì ‘Advanced Scholar’, instigated in the Sui dynasty, which is very roughly equivalent to a doctorate.

Those that passed the first, local Shenyuan ➚ ( 生员) exams automatically received minor privileges such as exemption from forced labor, effectively becoming middle class. Half of the candidates had no family history of passing the examination. The emperor often took personal control of the examination system, reading the essays submitted for the highest levels. The top Jinshi students were admitted to the prestigious Hanlin Academy. This academy was a pool of talent used for many Imperial purposes such as educating the emperor's sons, drafting edicts, advising on crises and administering the whole examination system. To become a Hanlin academician was the pinnacle of academic achievement and it brought great respect. The names of 51,624 Jinshi scholars from 1302 until 1905 are inscribed on 200 steles at the Temple of Confucius ➚, Beijing.

Ming dynasty reforms

The system became more sophisticated during the reign of the Ming dynasty founder Emperor Hongwu in 1382. Each prefecture (local district) had to have a school. Scholars who reached the Xiu Cai grade could then enter a provincial examination for the Ju Ren 举人 grade, held normally every three years. To pass this examination took years of study and it was rare for a candidate to be ready to take it before they reached the age of 30. The few that passed (5 to 10%) could then compete at national level at the capital city Beijing for the Jin Shi 进士 (Advanced Scholar) grade. To succeed at this level it was often necessary to have an influential patron who had been impressed by their scholarship and would then help with the candidate's studies and finances. Often a promising young boy would be supported by a syndicate of extended family and friends who would pay for materials, tutors and books. This was in the hope that if successful appointed as an official he would pay back his supporters and patrons with money, appointments and other benefits. A student would normally study in one of the many Academies ➚ (书院 shū yuàn) to prepare for the examination. On passing the Jin Shi examinations the lucky candidate would normally be offered a permanent and lucrative post in government. During the Ming dynasty only about 200 candidates reached the Jinshi level each year; so there were only about 3,000 top scholars at any one time in the whole of China.

During the Ming the works tested were changed to include the main works of Neo-Confucianism which had become the leading philosophy - particular the works of Zhu Xi. The success of the system led to its take up in neighboring Korea and Vietnam but not in Japan.

Image available under a Creative Commons license ➚

Image by User:FA2010 ➚ available under a Creative Commons license ➚

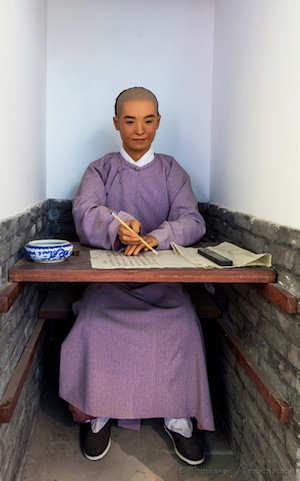

Strict examination rules

A typical examination involved being locked inside a single cell within a hall for several days and nights so candidates could not cheat, the essay they produced was marked according to strict criteria. It is said that at a Nanjing examination hall there were 35 deaths of candidates each day during their incarceration - a candidate could not leave even if they fell ill. Exact recall of the great Chinese classics (particularly of Confucius) was a key skill. The core works comprised about 400,000 characters so this was no mean feat, the whole Christian Bible is about 800,000 words. Memory rather than imagination was crucial to success. The eight legged essay ➚ (八股文 bā gǔ wén) was the famous test in Ming dynasty times, the answer had to be in 8 sections and could be no more than 700 characters in length. It should be remembered that old practices remained for a long period in Europe too; up until the 1960s it was necessary for candidates for British Oxford and Cambridge Universities to study the Classics in Latin and ancient Greek. It was only as late as 1855 that competitive written examinations were introduced for entry into the British civil service. In China, although accomplishments in the literary Classics achieved the highest prestige, examinations in law, economics, history and science were also available.

As there was no age limit, candidates could retake the examinations many times. So the temptation for those who only just failed to reach the grade was to try again and again. A well attested case is of a candidate continuing to take the examinations until he passed at the age of 72. In the Qing dynasty about 2,000 men took the test in each prefecture, only 1-10% passed to reach Xiu Cai grade. A pass was no guarantee of furtherance if no posts happened to be available that year. The famous Tang poet Du Fu failed the examinations while fellow poets Wang Wei and Su Shi achieved the Jin shi grade and entered the Hanlin Academy. In fact writing a poem was part of the examinations for many centuries. The novelist Cao Xueqin also failed but more importantly the rebel leader Hong Xiuquan failed the exams and he went on to lead the devastating Taiping Rebellion.

Fairness

Although it was ostensibly an open system but all candidates needed to be able to study copies of the classic texts and gain the advice and support of someone who had been through the process. So success often remained within ‘scholarly’ families as the help of fathers and grandfathers was a huge advantage. Only men succeeded, some women did try by dressing up as men, but none went undetected, only briefly during Empress Wu Zetian's reign were women allowed to enter for the examinations. In addition slaves, sons of merchants and actors were not allowed to take the exams. An important rule was that a candidate had to prove their name and ancestry by showing the family's ancestral tablet, if an ancestor had committed some misdemeanor, his name would not be on a tablet and so his descendents were barred from taking the examination. Examinations were however open to candidates from all parts of China, there was no bias towards Beijing locals; Jiangsu and Zhejiang were noted for providing good candidates. However the examination system was not the only route to a lucrative government post, patronage still recruited a fair proportion of officials. Over the two thousand years various reforms were instigated to try to keep the system as fair as possible. Papers were copied before marking so examiners could not identify a student by their calligraphy. This could be sidestepped by the candidate writing phrases at previously agreed points so the (corrupt) marker could still recognize the candidate's script. Candidates were known to bring in various cheat sheets on fans, clothing or written on their skin. In more extreme cheating, some candidates paid for scholars to impersonate them and sit the exam in their stead.

Image available under a Creative Commons license ➚

Modern Examinations

The decline of the traditional examination and education system came towards the end of the Qing dynasty. Western missions had started to found free schools and universities which taught 'modern' science and technology. Corruption had become widespread with bribes used to directly buy the qualifications without sitting the exam. The system ended in 1905 to be replaced with a National University Entrance Examination (Gao kao 高考 ➚). It has a wider range of subjects including science and technology in the standard three levels of schooling: primary, secondary and tertiary. The gaokao ➚ is sometimes criticized as still requiring too much learning by heart and continues to evolve. In the period 1949-89 Marxist thought formed a core part; during this era practical application was a compulsory subject so students would do some manual work as a part of the degree.

Anyone who has worked with Chinese students will realize that the cultural and historical emphasis on examinations continues to produce hard working and receptive candidates. In China it is still hard for anyone without a good university degree to rise to senior positions and so education defines life prospects far more than other countries where promotion on basis of work record is more common. People take them so seriously that any source of possible disruption is prevented (especially noise) while students are taking their exams. The continuing importance of educational attainment is based on a 2,000 year old profound respect for the importance of learning.