May fourth movement of 1919 - 五四运动 Wǔ sì yùn dòng

The May fourth movement of 1919 marked the start of the transformation of China into a modern nation and deserves to be more widely known.

China in the early 20th century

Although the Republic of China had been founded on January 1st 1912 the promised reforms went nowhere. The elected consultative assemblies that had been created soon fell apart and Yuan Shikai died soon after attempting to found his own Imperial dynasty. China entered a ‘warlord’ era where provinces were ruled as fiefdoms of militarist dictators, but this emergence of warlords was mainly in the north, in the south enthusiasm for the Republic remained strong. China was at its lowest ebb, bowing to any demand from foreign powers. Sun Yatsen had returned to southern China in 1917 and was calling for a re-unification of the country from his Guangzhou power base.

Even though the ‘Republic’ was the official government, the long hand of dynastic history was still in play. Emperor Puyi still lived in pampered luxury locked behind the walls of the Forbidden City with the title of ‘Emperor’ but with no power beyond its walls. Between 1911 and 1924 China had both a President and an Emperor - an absurd state of affairs that could not last. To the vast majority of poor rural people the Imperial system lived on, many expected a new dynasty to be established as had always happened in the past when a dynasty had collapsed.

The World Situation

In 1895 Germany had taken control of Qingdao, Shandong as a treaty port. [See our extensive section on the development of treaty ports in China]. The port had prospered (including the development of Qingdao [Tsingtao] beer), and so in 1898 Germany expanded its control to a large part of Shandong province 193 sq miles [500 sq kms] on a 99 year lease. Many foreign nations including Europeans, Japan and America were busy building up their interests in China. Indeed Britain and Germany worked together on a joint railway from Tianjin to Pukou which was completed in 1912 just before they came to conflict in 1914.

The outbreak of the First World War (1914-18) caused investment into China to evaporate. It became evident to all in China that the apparent peacefulness and mutual friendliness of the foreigners was not a permanent state of affairs - they were just as fallible as other nations.

Anti-Japanese movement

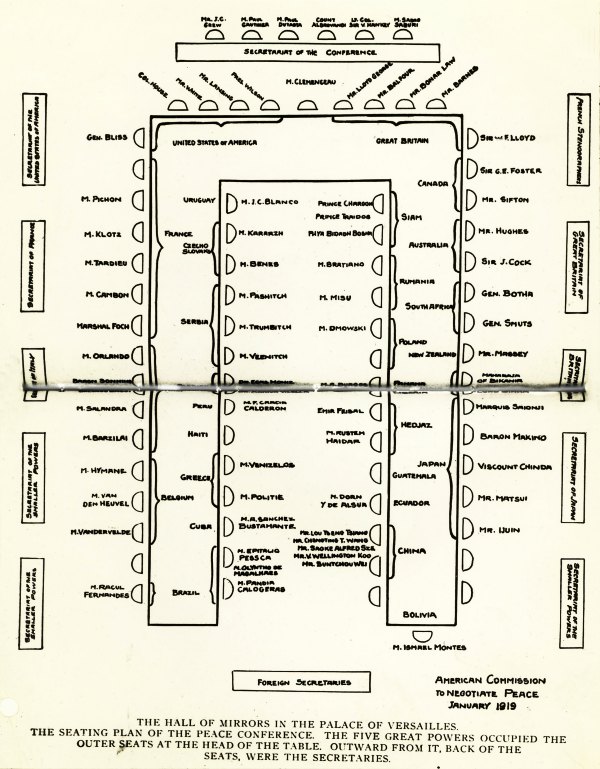

At the outbreak of war Japan chose to actively support the Allies against Germany and Austro-Hungary. As a long term British ally this was to be expected. Japan seized the opportunity by taking control of German territories. Japan declared war on Germany on 23rd August 1914. China joined the allies three years later on 14th August 1917. When the war was won in 1918 the victorious allies met together to negotiate the terms of the peace at the Palace of Versailles ➚ - including both China and Japan. The vexed question was what to do about the German overseas territories. China thought it had an agreement that the German occupied lands would be returned to Chinese control on an Allied victory. The Chinese delegation had demanded the end of the treaty port system, the restoration of Shandong to China and the abolition of the 21 Demands ➚ foisted on China by Japan. The Japanese diktats had been issued in 1915 and included such things as Japanese occupation of Fujian province. What was revealed at the Versailles talks was that the Chinese leader Duan Qirai had held secret deals with the Japanese. These provided Duan with the funds for military campaigns in return for accepting Japanese rights over Shandong. It was the Versailles Treaty negotiations that focused growing resentment of the Chinese government's acceptance of the Japanese demands.

The Chinese delegation was primarily led by Wellington Koo ➚ who, although a skilled negotiator, over-estimated his influence on U.S. President Woodrow Wilson. The foreign powers were concerned that restoring Shandong to China would create a dangerous precedent jeopardizing their areas of control within China. Instead the Versailles treaty agreed the transfer of all Germany's land leases to Japan. Not only did it stir up trouble in China but the vindictive treatment of Germany led pretty directly to World War 2.

Protest in China

When news reached China that Shandong had been lost at the Versailles negotiations, the response was of shock and horror, it was bad enough to lease land to European powers but to an Asian country, once considered a vassal state of China, was beyond imagining. The pro-Japanese stance of the Chinese government was fiercely opposed and the May fourth movement was born.

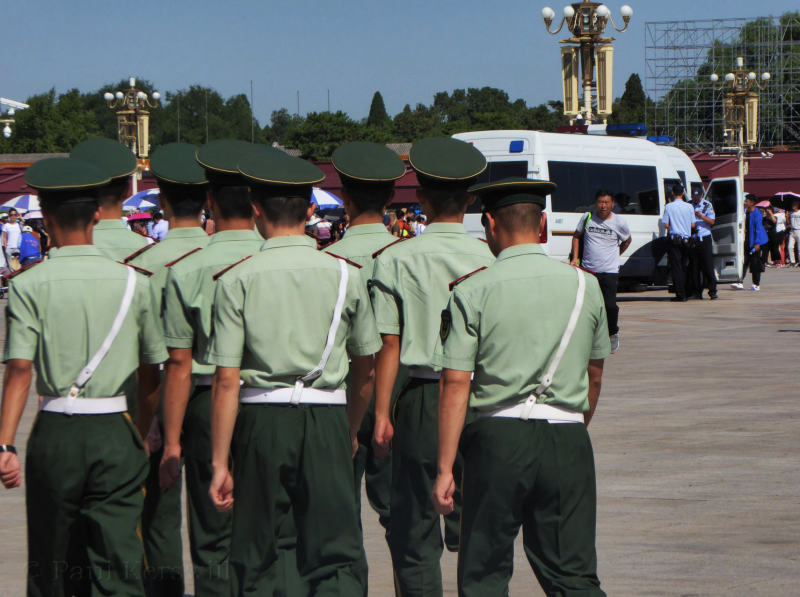

So on May 4th 1919 over 3,000 students mainly from Beijing (Peking) University gathered in Tiananmen Square at 1:30pm to protest. They marched to the neighboring foreign legation quarter with slogans such as ‘Return Qingdao to Us’ and ‘Boycott Japanese Goods’. Police blocked their way to the legations so the crowd turned their fury on ‘Japanese collaborators’ in the government. The houses of the pro-Japanese faction including Cao Rulin 曹汝霖 ➚, Zhang Zongxiang 张宗祥 ➚ and Lu Zongyu 陆宗舆 ➚ were attacked. The Chinese minister Cao Rulin's house was ransacked and some of his family and friends were beaten up. These protests were all over by 5:45pm but discontent rumbled on, a strike was called and the Beijing university students refused to attend lectures. On May 7th the students formed an association and sent messages throughout China for others to join them. Their call was answered and large rallies at Tianjin, Nanjing, Shanghai, Wuhan, Guangzhou (Canton) and Changsha took place. Mao Zedong, then in Changsha initially took little part; probably because his mother was terminally ill at the time. Chinese rallies in Japan were blocked by armed police. It was the first mass urban protest in Chinese history. The protests continued and 700 students were arrested on June 4th. However these arrests only brought about wider scale support. On June 5th workers began a general strike in Shanghai which grew by June 10th to about 70,000 people.

Deng Yingchao 邓颖超 ➚ described the events in Tianjin. She became the head of the Tianjin Women's Patriotic Society that held large rallies, printed propaganda and gave speeches in support of the May fourth movement. These protests were aimed principally ‘to save the country’ and not to install democracy or communism. Deng went door to door to spread the message. Zhou Enlai (Premier 1949-76) broke off his studies in Japan to work with a student organization in Tianjin. He became editor of the Tianjin Students Union newspaper which was published every day with 20,000 copies printed. Rallies were obstructed by armed police who often beat up the protestors. A large rally was held on October 10th 1918. Protests were made to Yang Yide (the Chief of Tianjin Police) but by November the protesting organizations were declared illegal and had to carry on in secret. A peaceful rally to deliver a letter of protest to Governor Cao Rui in December was met by further violence. Only after continued protests dragged on into 1920 were all the arrested students released from jail. Deng Yingchao records that female equality was achieved; the two protest groups were initially divided by gender but when they merged they worked together harmoniously with equal status - for the first time in China. Deng Yingchao and Zhou Enlai went on to be married in 1925. There was widespread support among Republican leaders, Sun Yatsen called for the students to be exempted from punishment because of their patriotic motives and at the other end of the reformist spectrum Kang Youwei thought the protests were a valid expression of 'people's rights'.

However the then President of the Republic Xu Shichang 徐世昌 ➚, who like Cai Yuanpei had become one of the last scholars at the prestigious Hanlin Academy, took the conservative view and tried to shutdown debate and protests. At its peak over 1,100 students were arrested and part of Beijing University was converted into prison cells to house them all.

The International Situation

The background to China's treatment at Versailles needs to be understood to help explain these events. At this time Britain remained a key player, it remained the number one world power and had invested heavily in China. The UK still saw Shanghai and the whole Yangzi valley as an area ripe for development. Shanghai was at the time ‘international’ but dominated by the British who regarded it as Britain’s ‘Open Door into China’. The ‘Great Game’ with Russia had come to an end when Russia joined the alliance against Germany and deposed the Tsarist regime. To avoid deploying British or Indian troops in the region, Britain had turned to Japan as its main ally in the north to frustrate Russian expansion. The Anglo-Japanese Alliance ➚ was signed in 1902. It is not surprising that Britain encouraged Japan's move into Shandong. Indeed British forces helped the Japanese take control in 1914. Britain had already its own foothold in Shandong at Weihaiwei where the port was leased in 1898 for as long as the Russians occupied the Liaoning peninsula.

The Japanese situation is quite hard to understand because of the events that were to follow in World War 2. At the time many Chinese reformers (including Sun Yatsen) had visited Japan to understand its rapid modernization and see how this approach might be applied to China. It was the shining example of how an Asian country could rapidly reform. Japan had a form of constitutional monarchy similar to Britain with the hereditary head of state having little actual power. Many saw the Japanese as the natural successors to the Manchus (Qing dynasty) as a race that would conquer China and bring about much needed change. Indeed when the Japanese invaded China in 1937 it took note of Manchu invasion tactics from 300 years ago. This may seem unrealistic in retrospect but at the time the success of Japanese modernization of the island of Taiwan seemed a reasonable model to apply to China as a whole. Taiwan had become a Japanese possession after the Sino-Japanese War (1894-5) and had remained relatively peaceful and was prospering. As part of the 21 Demands Japan sought to occupy neighboring Fujian province as well. Japan had seized the German Shandong possessions in 1914 and as a war-time ally must surely have expected to cling on to them as a reward for its support.

Meanwhile in south-west China (especially Yunnan), France was extended her influence from French Indo-China and had leased the region of Guangzhouwan in 1898 for 99 years. France must have been keen to avoid the precedent of returning leased land back to China that might damage her colonial system that included Vietnam and Cambodia.

It is however the revolution in neighboring Russia that proved more significant. Without it the protests would probably have been much more muted and fizzled out. Russia had had its revolution in 1917 and installed a government based on Marxist/Communist ideology. The novelty of a classless society had great appeal to young Chinese.

Protestors' Victory

Central government, such as it existed, eventually caved in to the demands of the May Fourth movement. The leaders of the Pro-Japanese faction were dismissed from government and the students were released without charge. More importantly the Chinese delegation at Versailles refused to sign the treaty. The main contention - giving Shandong to Japan - had to wait until the Washington Conference ➚ (1921-22) to be finally resolved; there U.S. President Harding concluded an agreement on February 4th 1922 that ordered Japan to revert Shandong to Chinese control. However many Japanese continued to remain there in a privileged position. The success of the May the Fourth movement had wide ranging repercussions. The seeds of a genuine nationalistic mass movement had begun which would ultimately lead to the formation of the Peoples Republic in 1949. China had ‘stood up’ to foreign exploitation for the first time since Lin Zexu burned the opium at Guangzhou in 1840. The reformist vigor had at last spread from the south to all of China.

However it was only urban centers that became politically active, the great majority of Chinese people in rural areas continued life unaffected and were barely aware of the protests. China did not follow the same path as Russia had just 18 months before in its October Revolution. Although Marxism was seen as the most appealing philosophy behind the movement, it was nationalistic rather than communist. The priority was to save the nation and not to change the system. However women's rights was an important part of the message and many young women took an important part in political activities for the first time in Chinese history on an equal footing to men.

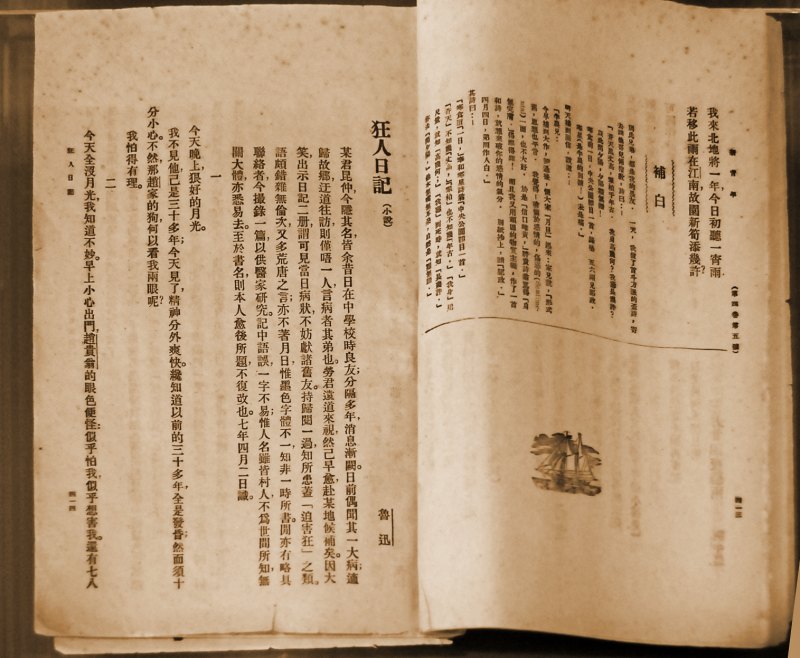

The president of Beijing University, Cai Yuanpei 蔡元培 ➚ (1868-1940), was seen as an inspiring figure of the May 4th movement. Hu Shi 胡适 ➚ and Chen Duxiu 陈独秀 ➚ were also active in the early days at the faculty. Chen Duxiu was the editor of the influential ‘New Youth’ periodical which was avidly read by both Jiang Jieshi (Chiang Kaishek) and Mao Zedong; another very famous contributor was Lu Xun. Chen Duxiu went on to co-found the Chinese Communist Party in 1921. In this and other publications the vernacular form of written Chinese became generally accepted and this widely expanded its readership beyond the privileged class of scholars and officials. Some believe this was the most significant achievement of the movement.

The students were seen as the trailblazers for a new form of society and by writing short periodicals and organizing rallies, the fervor for change was maintained. They had eventually achieved victory over the government by determined action. A national Republican government had achieved widespread appeal.

All this may seem a fairly tame protest movement as has happened all over the world in many countries. But in China the May Fourth Movement was much more than that, it was a pivotal moment when entrenched attitudes were challenged and defeated. The May Fourth event was as significant as the Age of Enlightenment ➚ in Europe. Ideas were no longer the property of just the educated elite but of all of the people. Everyone in China became engaged in considering for themselves the new place for China in the modern world.