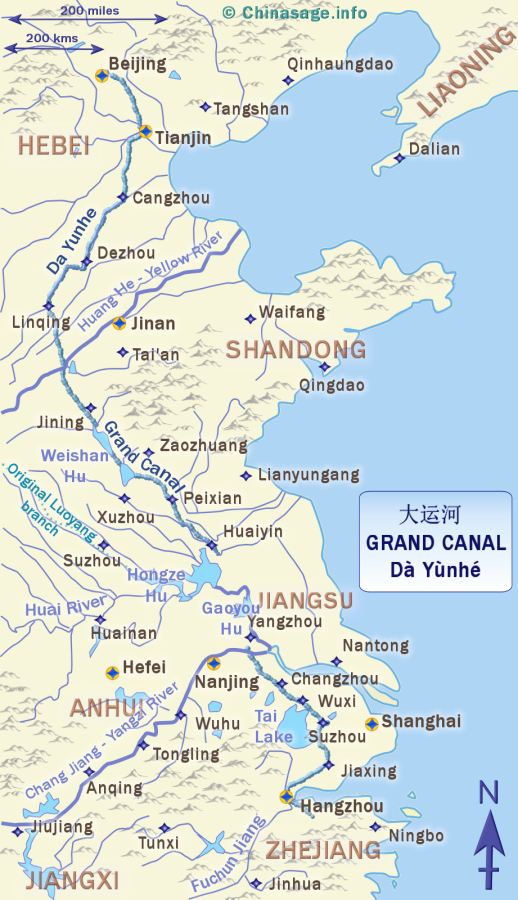

Map of China's Grand Canal

China's Grand Canal or Emperor's Canal

The Grand Canal (大运河) Da Yunhe is a waterway of amazing grandeur and importance. Linking north and south China it provided safe transportation insulated from the threats of storms and pirates on the high seas. Just as significant to China as the more famous Great Wall it is a testament to the immense organized manpower used in its construction. It spans 1,100 miles [1,770 kms] making it the longest canal system in the world. It is also known as the 京杭大运河 JīngHáng Dà Yùnhé where ‘Jing’ stands for Beijing and ‘Hang’ for Hangzhou - naming it the ‘Beijing Hangzhou grand canal’. Another old name is the ‘River of Locks’ 闸河 Zhá hé, it is roughly equal in length to the distance between New York and Florida or London and Tangiers.

Like the Great Wall it was not all built at the same time as a single project. The earliest section from the Yangzi river north to Huaiyin (the Shanyang canal) was built as early as 486BCE and is shown in turquoise on the map. A separate early section from Suzhou to the Yangzi was built a little later in 495BCE. Boats were pulled by teams of oxen, horses or men along a tow path. The main building phase came during the Sui dynasty when Yangdi commenced the project in 605CE with the building of sections from the old capital at Luoyang to Beijing and from the Luoyang on the Yellow River to Hangzhou. The majority of the canal was made an impressive 131 feet [40 meters] in width. Incredibly, as many as five million people, including women and children were conscripted into the project. The cost in human lives was huge, perhaps 2 million workers died. All men aged from 15 to 50 were liable to be called up. When it was finished Emperor Yangdi sailed a Dragon fleet with 80,000 men pulling the boats, some of these boats were huge with 120 rooms.

How it was built

Mostly built over the flood plains of eastern China made by the wandering Yellow River, long stretches are flat and so were easy to construct. Some sections needed to be made above ground level requiring huge levees to be built up so that a deep excavation could be made for the navigable channel. Near the edge of Shandong at Jining there are locks to allow it to climb the foothills of Meng Shan. This section was built around 1280CE to shorten the length by about 435 miles [700 kms]. There are also locks to take it down to the level of the Yangzi river at Yangzhou. At this time a lock was typically a 'flash' lock, a boat raced down a slope on a shallow burst of released water. The more familiar modern 'pound' lock with gates was invented around 984. The pound lock ➚ is much safer for the boat and uses far less water. Although the Grand Canal is a mighty transport artery, travel is very slow, with journey times of about one year from end to end. Such a length of time renders it unsuitable for transport of perishable goods, but silk, wood, coal, bricks and porcelain could all be transported as bulk freight. Rice from the south traveled up to the north (100,000 tons a year in the Tang dynasty) this was, historically its most important freight. Like the Nile in Egypt, the Grand Canal served as a vital lifeline for food from the agricultural south to the urban north.

Extension to Beijing

When Hangzhou was the capital of China during the Southern Song dynasty the southern section, south of the Yangzi had great importance. A new route via Hongze Lake was introduced. Later in the Yuan dynasty the canal was further extended to take the canal directly to the new capital at Dadu (Beijing). The new route bypassed the sections taking the canal on the long detour to Luoyang, reducing the total travel time considerably. The route of the original canal to Luoyang is shown on the map. However the frequent floods of the Yellow River and droughts made this section unreliable and the northern stretch fell out of use. Grain transport to Beijing moved to the sea by way of the port of Tianjin.

Decline and modern revival

Marco Polo, who visited during the Yuan dynasty, was greatly impressed by the transport system of massive barges hauled by teams of horses on the towpath. The canal needed regular and expensive maintenance to keep it navigable. In the Ming and start of the Qing dynasties the cost was put at 10-20% of total government expenditure. During the late Qing the maintenance of the canal was not kept up, in 1824-6 part of the canal silted up and prevented the transport of grain by boat. After the Taiping Rebellion (1850-64) the canal fell into rapid decline, as railways were built and transport in larger boats by sea became much more economic. By 1900 the northern sections had become silted up by the waters of the Yellow river and the original route of the canal is so faint that the precise route is disputed. South of Jinan the canal, like many canal systems in the world is now more of a tourist attraction than a transportation system (particularly from the stretch from Yangzi to Hangzhou). However coal is still shipped south from Xuzhou to Shanghai in long trains of up to 30 barges and 305 meters [1,000 feet] the canal is also used to divert water from the Yangzi to arid parts of Shandong. The northern section is due to be revitalized not as a transport link but to carry much needed water ➚ from the Yangzi to northern China.