Chinese Women

Chinese women in history

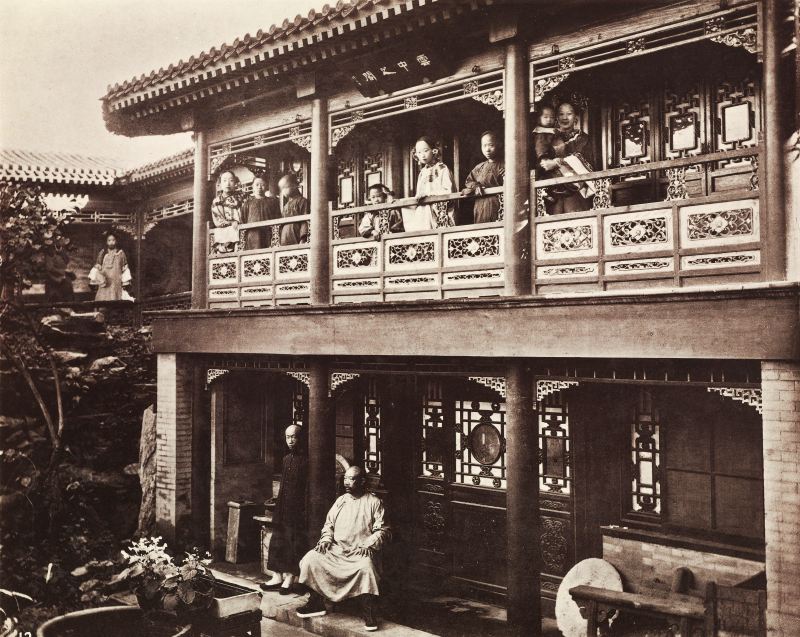

We look at the changing attitudes to women in China over the centuries.

Early dynasties

In common with other world cultures in early times the role of women in China was more significant than in later centuries. The tomb of Lady Hao (Fù Hǎo 妇好 d. 1200BCE) of the Shang dynasty reveals that women in this early dynasty could reach a high position, and it is believed that she led military campaigns. However men soon started to take the principal roles in society. The attitude to women changed as can be seen from one of the early Classics, in the ‘Book of Odes’ (Shijing), written in the later Zhou dynasty there is the Zhan Yang ➚ admonishment:

哲夫成城、哲妇倾城

懿厥哲妇、为枭为鸱

妇有长舌、维厉之阶

乱匪降自天、生自妇人

匪教匪诲、时维妇寺

To counterbalance this view there is also an old Chinese proverb A man knows but a woman knows better.

Han dynasty women

The Han dynasty set many conventions and traditions that lasted for the remaining two thousand years of Imperial rule. The leading doctrine became Confucian which sought to put everyone in their proper relationship and in this regard women were put below men.

A bride serves her husband,

Just as she served her father

Her voice cannot be heard

Nor can her body or shadow be seen

With her husband's father and elder brothers

She has no conversation.

According to Confucius, women should first be totally subservient to her parents and then to her husband. Although women had equal rights they must follow their parents and husband in all things. Women were taught to take the lowliest role and undertake the most menial duties. They were instructed to follow the ‘Three Obediences and Four Virtues’ 三从四德 Sān cóng sì dé: obedient to father, to husband and to sons as a widow; and the virtues: morality, genteel speech, modest appearance and diligence. Confucius himself divorced his wife after four years of marriage for no apparent good reason. The birth of a girl became a cause of regret that it was not a son. The tone is set in the Han classic by Liu Xiang ➚ ‘Biographies of Heroic Women’ in which the lives of 125 gallant and unselfish women are described. Another Han classic written by Ban Zhao ➚ ‘Admonitions to Girls ➚’ teaches the proper subservient behavior. Unstinting and long service to men was the aim to be followed by women. She describes how a baby girl on its third day of life would be placed under the bed to emphasize her inferior position in life. However, this position was not universal, Ban Zhao is noted as the first significant female historian. She came from a famous family with General Ban Chou ➚ and historian Ban Gu ➚ as brothers. In general women were regarded as the inferior gender, women were punished more severely for offenses than men. The strict division of sexes according to Confucian precepts is set out in the Liji Qu Li I ➚ ‘Rules of propriety’:

Male and female should not sit together (in the same apartment), nor have the same stand or rack for their clothes, nor use the same towel or comb, nor let their hands touch in giving and receiving.

The rule forbidding the passing of any object between husband and wife was widely followed, they were not allowed to risk touching hands (even up to 1949). Women were virtual prisoners at home, with the husband buying his bride.

However, another strong Chinese tradition could elevate women's status above men. Subservience to parents was more important than from wife to husband so a man had to do whatever his widowed mother wished, and these mothers were often the dominant force in the household.

Women in later dynasties

Traditionally the ideal woman was slim, delicate and refined. Ideally a woman's mouth and lips should resemble a cherry and the teeth should be white and straight. The face should be egg-shaped not round and the eyes like almonds. The body should be slim, supple and curved with narrow hips and small breasts. Women did not mingle in society and were rarely seen on the streets. They avoiding being seen out walking and rich women traveled in sedan chairs with their faces hidden behind veils and curtains. Even doctors (all men) were forbidden contact, a woman had to indicate on a special ivory model as to where she felt pain so the doctor could diagnose without examining or touching. When foreign visitors visited towns they reported that they had not see a single woman.

In the Tang dynasty some popular love stories were written promoting love not duty as the bedrock of relationships. The increasing wealth of Song dynasty China enabled women to take a more prominent role: as poets, courtesans, singers, running inns and so although many were confined to home (carrying out child-rearing) they did have some greater freedom. Another crucial role they played was in the careful and lengthy process of matchmaking for their children. Learning to read and write was acceptable for richer women but making a living as a poet was very rare. Women wrote many letters but were effectively blocked out of the scholarly elite with only one or two exceptions. Girls were separated from boys at the age of seven and began their separate education in domestic duties.

The general attitude to female education is summarized in this quote “Why should we think? Our husbands are kind to us; we have but one dream, and that to make them happy, and if there were more thinking than that our foreheads would be nothing but wrinkles, and then we would be no longer be loved.”

Later in the Yuan dynasty Guan Daosheng ➚ was the first female painter to achieve widespread fame proving that attitudes to women were not universal. In the 18th century ‘The Dream of the Red Chamber’ was a book that championed love and romance in relationships compared to the reality of the traditional arranged marriage. Moves towards the equal treatment of women had to wait a long time. It was one of the principles set out by the Taiping rebels in the mid 19th century although not widely brought into effect.

Imperial women

The Empress held great power within the Imperial palace, but most wielded their influence from behind the emperor's throne. There are three noted women who rose to rule in their own right. The first is Dowager Empress Lu ➚ who took control after death of the first Han Emperor Liu Bang. She was the effective ruler of China for seven years and sought to bring her own family into power. However on her death in 180BCE most of her family members were put to death.

On the rise of another strong Imperial dynasty, the Tang, Empress Wu Zetian ruled first through Emperor Gaozong and then as regent for their two infant emperor sons Zhongzong and Ruizong. For a full description of this determined woman and her reign of 15 years please read our section on Empress Wu Zetian. She sought to equalize the role of women in society and, all too briefly, women were allowed to sit the Imperial Examinations.

The third great Imperial woman was Dowager Empress Cixi who reigned over the dying embers of the Qing dynasty. As with Empress Lu she ruled as regent over infant emperors but never took supreme power in her own name. Her life is still being reappraised, once blamed for decadence, incompetence and opulence she is now being seen more as a victim of her time, trying to bring some order to a fatally flawed system.

The more typical role for an Empress was as a loyal wife and supporter of the Emperor – following the Confucian doctrine for women's behavior. The most revered Empress is therefore Tang Empress Zhangsun ➚ (601-635) who gave sound advice, lived a comparatively frugal life and gave her children a good grounding for their future roles. She prevented her husband Emperor Taizong from acting upon his many unwise impulses and quelled his temper tantrums.

Modern times in China

Towards the end of the Qing dynasty, fueled by increasing contact with the west, women began to complain about their situation. Chinese diplomats were astounded by the rights and freedoms of some of the high society women they met in Europe and America. An early fighter for republicanism and the rights of women was Qiu Jin ➚ [1875-1907], she published this piece in 1904:

We, the two hundred million women of China, are the most unfairly treated objects on this earth. If we have a decent father, then we will be all right at the time of our birth; but if he is crude by nature, or an unreasonable man, he will immediately start spewing out phrases like “Oh what an ill-omened day, here’s another useless one.” If only he could, he would dash us to the ground. He keeps repeating, “She will be in someone else’s family later on,” and looks at us with cold or disdainful eyes.

Before many years have passed, without anyone’s bothering to ask if it’s right or wrong, they take out a pair of snow-white bands and bind them around our feet, tightening them with strips of white cotton; even when we go to bed at night we are not allowed to loosen them the least bit, with the result that the flesh peels away and the bones buckle under. The sole purpose of all this is just to ensure that our relatives, friends, and neighbors will all say, “At the so-and-so’s the girls have small feet.” Not only that, when it comes time to pick a son-in-law, they rely on the advice of a couple of shameless matchmakers, caring only that the man’s family have some money or influence; they don’t bother to find out if his family background is murky or good, or what his character is like, or whether he’s bright or stupid ? they just go along with the arrangement. When it’s time to get married and move to the new house, they hire the bride a sedan chair all decked out with multicolored embroidery, but sitting shut up inside it one can barely breathe. And once you get there, whatever your husband is like, as long as he is a family man they will tell you you were blessed in a previous existence and are being rewarded in this one. If he turns out no good, they will tell you it’s “retribution for an earlier existence” or “the aura was all wrong”.

The real change came with the foundation of the Republic of China when the May Fourth movement founded in 1919 pushed for the equality of women. These changes only helped some women living in the cities, they were not adopted everywhere, universal reform of the age-old marriage traditions had to wait until Mao Zedong came to power in 1949. The Marriage law of 1950 removed many of the old rules and brought in a great deal of equality between the sexes. Mao proclaimed in 1952 that ‘women hold up half the sky’ demolishing the tradition that only men had a link to heaven. Women could now divorce men, and men could not keep concubines. There were no longer dowries or division of estates to favor just their sons. Women were allowed and encouraged to take up jobs that used to be men's preserve including administration, working in heavy industry and in the fields.

A national Women's Day is held on March 8th each year to mark the special contribution of women. It is a half-day holiday for all women and was inaugurated in 1975. The One Child Policy brought in 1980 had a huge impact. When a family are forced to have only one child they treated girls just the same as boys, there was no potential for preferring a brother. Another more recent pressure has been brought about by the severe gender imbalance, with as many as 125 boys to 100 girls (Henan and Hubei provinces) the scarcity of marriageable girls has improved their status.

However it has to be said that since about 1990 the status of women in China has gradually diminished. All the higher positions in government and commerce go to men and there is huge pressure for women to be attractive to men and the ambition is to marry well rather than have a career. There have never been any women on the top Standing Committee of the Politburo and none on the wider 20th Politburo. The highest woman currently serving (2023) is Vice Premier Sun Chunlan ➚. Women are often recruited on basis of looks rather than merit and in 2012 only 6% of company directors were female. Sexual harassment is common place at work. Sadly all the pressure takes its toll, China is the only country in the world where there are more female suicides than male (150,000 a year). In fact there are more female Chinese suicides than the rest of the world put together. It is now becoming common for the very rich to have one or more mistresses who are given their own houses - in essence a continuation of the system of concubines.

The modern writer, Xinran ➚ has written movingly about the plight of women in modern China. Her book ‘The Good Women of China ➚’ contains reports of interviews with women who have suffered in the not too distant past (1940-2000). Her regular phone-in program at Nanjing ‘Words on the Night Breeze’ encouraged women to unburden themselves about their secret lives of suffering.

Traditional views about women

The ancient Daoist tradition of yin and yang has had a deep influence on the lives of men and women. The yin is identified with the female: the receptive, the cool and the dark while yang is light, powerful and male. As these properties are opposites, this tradition polarized the position of men and women in society.

Another key tradition that has led to the inferior position of women is that only men could perform the ancestral rites, without these rites the ancestors were expected to bring misfortune on their living descendents for failing in their duty. It was this belief that required a father to produce a son. The worship of ancestors was a phallic ritual, as it sought the fertility of women and the soil through men. Unlike in the west there is no tradition of ‘gallant’ behavior towards women: opening doors, giving up seats and so on.

Buddhist nunneries have proved a refuge at time of troubles for women over the centuries. Due to the Confucian doctrine of superiority of the male, the alternative Daoist and Buddhist religions were attractive to women. The missionary efforts of Christians also recruited many women who could then study to gain skills normally forbidden to them. However this proved counterproductive when the work of Christian missionaries was seen as a foreign and alien doctrine at the time of the Boxer Rebellion.

Cultivation of silkworms was a female dominated occupation, it was labor intensive but not arduous and much of it could be done indoors. As it was considered unseemly for women to expose skin except for face and hands, working in fields was rare, women were restricted to the house and garden. The gender roles were reinforced by superstitions, for example: women could not work in fields because the potatoes they plant would not sprout and melon seeds planted would be bitter. However the lot of women was not unduly onerous, they lived within the family home with the children and had the companionship of other women in the extended family. It was often the husband's mother who sought to control her son's household and this could cause great upset to his wife. The Confucian doctrine of honoring all wishes of parents means a husband has to go along with his mother's wishes for running the household and this did sometimes lead to tyrannical rule. There is a traditional saying ‘A bitter wife endures all before she becomes a mother-in-law’.

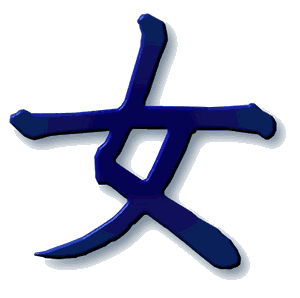

Women in Chinese Characters

The Chinese radical nu (女 nǚ) is used to give a female connotation to many characters. It gives both positive and negative meanings and is rooted in historic attitudes. There is good 好 hǎo made up of woman and child that is definitely positive. The use in peace 安 ān with a woman under a roof suggests the home as a peaceful haven.

As you might expect the character for marrying a woman 娶 qǔ has a female component, the top section hand and ear represents take, with no evidence of affection. A character showing the early high status of women is 姓 xìng surname that suggests that family names in early times were passed from mother to her children. jiāo 娇 has the meaning of tender, lovable, charming. Female relatives often include the female radical; so there is 妈 mā mother 姐 jiě elder sister 妹 mèi younger sister and of course 妇 fù woman , 她 tā she; her. There are many more characters, some showing the negative historical attitude: 奴 nú is slave and 奸 jiān is crafty, disloyal, adulterous. The old form of the jian character was 姦 made up of three copies of the nu female radical. The character 嫉 jí is envy, jealousy while 妙 miào ingenious and finally 妍 yán is beautiful.

On the foundation of the Peoples' Republic in 1949, attitudes and names changed. The traditional term for wife 内人 nèi rén meaning person indoors became 爱人 ài rén loved one. The equality was underlined by the universal greeting 同志 tóng zhì comrade which literally means same purpose instead of ‘Mr.’ and ‘Mrs.’ but nowadays comrade has disappeared from ordinary use.

The Chinese word for marriage is 婚姻 hūnyīn while the wedding ceremony is 婚礼hūnlǐ. Both characters contain the woman radical 女. With regard to marriage the character most associated with it is called 双喜 shuāng xǐ meaning double happiness - very appropriate for a wedding. The two joined characters 喜喜 will be seen at weddings in the form of paper-cuts and many other representations.

Traditional Marriage in China

Marriages in China were arranged by the parents often with the aid of a matchmaker (usually a woman 红娘 hóng niáng or 媒人 méi ren). An informal agreement for a marriage alliance between two families sometimes took place even before children were born. The matchmaker took astrological readings of the potential matches checking for compatibility. The readings centered on the bazi 八字 eight characters, which recorded the exact hour, day, month and year of conception. The matchmaker would then make a choice and write the bazi on red paper to give to the families. If both sets of parents approved, gifts were exchanged and the couple were then formally betrothed. It was quite frequent for a boy to be betrothed by the age of ten. A wife would not see her husband before the marriage ceremony itself; indeed a chance meeting between the betrothed was considered possible grounds to call off the marriage. Although in some regions a social meeting in the company of parents and others would be permitted. This tradition had the effect that all rich men's sons would be betrothed by early childhood.

Love marriages without parental consent were very much frowned upon. If an engaged man died then the fiancee could choose to be treated as a widow and sometimes adopted a nephew of her intended as her own son, thus continuing the male line of the deceased. If she chose not to live as a widow, the dead man would sometimes be married to an unmarried woman who had also died, and so maintain a unique pairing. These ‘ghost weddings’ were not unusual. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries the rules relaxed a little in cities, a husband could select a potential bride but it would still be the parents who would decide whether to permit it or not.

All the rules of marriage were enshrined in secular law with severe penalties if broken. If a bride had been said to be beautiful when she was not, the bridegroom could decline the marriage.

Marrying a stranger

There was an ancient rule of always marrying outside the extended family, you could not marry someone with the same surname even though very distantly related. In rural China one large family or clan tended to live together in one village; so this custom required seeking a wife from further afield. Families used to shop around for the best wife at the best cost for their sons. A family with many daughters were in financial trouble as they lose the work and income of the daughter when she marries hence the saying “There is no thief like a family of five daughters”. This rule had the repercussion that sons were preferred to daughters because once married, daughters would leave the village and could no longer help with her parent's work. A bride lost contact with her own family and looked on her husband's parents as her own. Importance was put on the male line, so that even though you could not marry someone with the same family name you could marry a cousin if they had a different family name, this is because the male line was considered dominant. It was common for one family to inter-marry with only a few other families. The wife keeps her own family name on marriage, so there is no ‘Mr. and Mrs. Smith’ convention. The children usually take the father's family name but may choose to take their mother's name (particularly if it is an illustrious family). The traditional marriage law applied equally to the Imperial family, this forced an Emperor to elevate the Empress's family to influence, which proved a source of intrigue and revolt down the centuries. The Empress had most power when the Emperor died and she operated as Dowager Empress until a young heir came of age. As the Empress's family lost influence on the heir's accession, they would often desperately seek to keep the Emperor in good health.

Once a betrothal had been made it was hard to break and the engagement could last for years. Sometimes people were betrothed while still very young even though they would not marry until many years later. In most cases the man would be a couple of years older than the woman. Officially the age for marriage was between 20 and 30 for men and between 15 to 20 for women. Failure to marry was seen as aberrant and officially discouraged.

Traditional Wedding Day

On the wedding day the bridegroom went to the bride's family house, where his access was ritually denied until he had presented gifts. The choice of date is made very carefully as some days are considered unlucky, even numbered days are preferred and the seventh month forbidden. The bride would be surrounded by lanterns as the ceremony often took place at night. Emblems of the dragon and phoenix were often used on gifts, as they represent conjugal bliss. A feast then took place but the bride remained in her bridal chamber awaiting her new husband who arrived at night. Symbolizing future parenthood a young child would often be in the bridal chamber to greet the bride and groom. The couple traditionally kowtowed at the ancestral altar honoring all the parents. The bride permanently moved away from her own birth family to that of her husband. Red is the lucky color for marriage and many decorations are in red. Lucky money is exchanged in red envelopes and the bride and groom drink wine from two cups linked by a red string. Traditionally this was a single gourd cut in two. The wine if offered by the groom to the bride and then groom to bride, they then both drink. This honors the legend that the God of Marriage links the bride and groom with an invisible red thread from birth. Other items in the bridal chamber were copper vessels (because 铜 tóng ‘copper’ sounds the same as 同 tóng ‘together’ and also shoes as shoes stay together as a pair). A salvo of firecrackers are set off as at other festivals. An ax (fu 斧) wrapped in a red cloth is the traditional gift to the bride. It symbolizes the end of virginity but also fu is a homophone for happiness 福. Eggs dyed lucky red are also a traditional gift. A gift of chopsticks kuai zi 筷子 symbolizes the hope for newlyweds to have children quickly because kuaizi sounds the same as 快子 ‘fast sons’; it also sounds like 块 kuài which is a colloquial term for money. In places there was a tradition of ‘disturbing the new house’ where the shyness of the new couple was broken with games and encouragement by the neighbors (similar to the old American tradition of Shivaree ➚).

There was a great rush to get married should the Emperor become ill. This happened because should the Emperor die there could be no marriages for the period of mourning - sometimes a whole year for those at court, 100 days for ordinary folk. It was also forbidden to marry in the three years of mourning following the death of a parent. All these traditions have pretty much disappeared although there are still some matchmakers.

Infanticide

In modern times we are used to a low infant mortality rate. In China in 2005 the rate was about 2%, but as recently as the 1930s mortality rates were as high as 50% or even higher. To be sure to leave surviving children women had many babies and each birth brought a high risk to both mother and child. Child-bearing put a heavy burden on women over many centuries.

Having children was seen as a key duty of the couple. There was a traditional ceremony on the 15th day of the 8th month for village children to put melons in the beds of childless couples. Melons symbolize having many children and it was not so subtle a hint to 'do their duty'. A mother's confinement is fairly strict and can last a full month.

As the daughter moves away to another family and village when she marries, the family that had invested in her upbringing receive no benefit. So the tradition of favoring sons is based on cold economics rather than any misogyny. Female infanticide and abandonment is much exaggerated, it took place only when families were literally dying of starvation and had no way to support the new baby. Although boys were preferred, girls were still very much prized and loved. Those with a strong belief in Buddhism could justify infanticide on the basis that it was in a child's best interest; as instead of likely starvation there is always hope that the next re-incarnation of the child would be more lucky.

Child brides

Among the poorest there was the tradition of ‘child brides’ 童养媳 tóng yǎng xí as a way of allowing girls to escape the likely fate of starving to death. The girl as a young child would be given as a ‘bride’ to a wealthier family, although sometimes some money was paid. The girl was treated no better than a slave by her new family until eventually becoming a wife of one of the younger sons. The strong gender imbalance resulted in a shortage of women to marry and so the child bride system guaranteed the availability of a wife from an early age.

Divorce

Although divorce in China was illegal, an informal divorce or permanent separation (instigated by the man) was fairly straightforward, it was actually easier to break off a marriage than a betrothal. However if a substantial dowry had been paid this would cause friction between the families. The divorce laws favored the husband but the wife had some grounds for leaving her husband, but re-marriage of a woman after a divorce was rare. On divorce the woman was required to return any goods, money acquired during the marriage to her estranged husband's family - a very strong incentive to stay together. Running away from a husband was considered a punishable crime and a woman's grounds for legal divorce were very strict.

Golden Orchid Society

In southern China, in the nineteenth century, the Golden Orchid Society of women rejected marriage. They vowed to commit suicide rather than enter a forced marriage. Some of the members married as lesbian couples, others abstained from all sex. The authorities saw the Golden Orchid Society ➚ as a threat and took measures to brutally suppress it.

Widows

Traditionally when the husband died the widow would not remarry. However in rural communities a childless widow who could not be supported by her in-laws sometimes remarried a brother or cousin of her dead husband. It was not uncommon for a widow to commit suicide, this was not considered dishonorable as it is in Christian countries. There was no punishment for attempted suicide and Chinese religion does not punish suicides in the afterlife, indeed some famous suicides had honor heaped on them as in the case of Qu Yuan. The veneration of virtuous women was really a tactic to keep up moral standards. However far more women than men committed suicide, especially young childless widows. This was partly due to the stigma attached to remarriage. Memorial arches (a form of Paifang 牌坊) used to be built to commemorate pious widows who had refused to remarry. However the situation was not equal between the sexes; it was expected for men to quickly re-marry after the death of his wife.

Concubines

There is a widespread belief that Chinese tradition supported polygamy (multiple wives) but the actual situation was more complex. A man had only one wife but he could also take concubines. A concubine was a lower class of wife who lived within the extended home and if she bore him children they would be treated the same as his wife's children. It was expensive for a man to support a wife and several concubines and so the tradition was restricted to the better off and inevitably became a badge of pride as to how many concubines he could support. Agencies grew up who would help find suitable concubines for a fee for their rich patrons. The Emperor would have hundreds if not thousands of concubines but there would still be only one Empress. The Emperor divided his concubines according to grade, there were fourteen ranks from ‘beauty’ to ‘brilliant companion’ and ‘favorite beauty’, living in separate halls with exotic names such as ‘Residence of Seeking Perfection’. A concubine had a scaled down version of the betrothal ceremony, with money often given to the concubine's parents. The wife could expel a concubine without the husband's consent so the concubines worked as her willing servants and were usually of lower social class. Each concubine would have a separate small dwelling within the home. Men would sometimes take concubines when his wife failed to produce the son that tradition dictated, it was done openly and without the animosity that might be expected. The practice was made illegal under the Republican government, but it was not really until the marriage law of 1950 under the People's Republic that concubinage came to an end.

The most famous example of a concubine reaching high prestige has already been mentioned, it was Dowager Empress Cixi. Because she bore Emperor Xianfeng his only surviving son, even though a concubine, she became the Dowager Empress on Emperor Tongzhi's accession in 1871 and the most important person in China until her death in 1908.