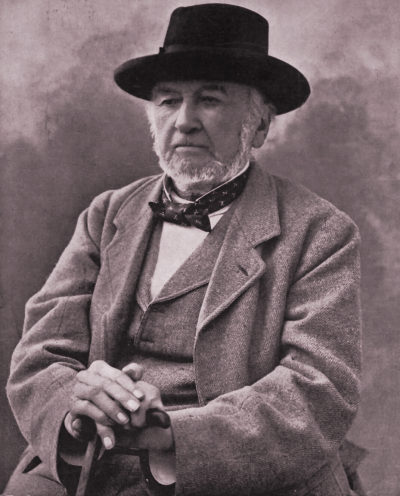

General Charles Gordon [1833 - 1885]

The list of British heroes has changed greatly over a hundred years. Back in the early 20th century most British people would put ‘General Gordon’ at the head of the list'. But this ‘Gordon of Khartoum’ first came to fame for his exploits in China long before his ill-fated involvement in Sudan. General Charles Gordon came to epitomize all that was ‘good’ and ‘heroic’ about the British Empire but he now would be listed as an ‘anti-hero’ who was involved in aggressive military campaigns to expand the Empire’s borders ever wider. This modern view is just as faulty as that of 100 years ago. But why was he also known as‘Chinese Gordon’ and why did he have amongst his possessions the throne of the Chinese Emperor and a gold medal struck especially in his honor by order of the Emperor?

If you look through Chinese history books you will see Gordon mentioned as a mere footnote. Certainly something must have changed, as this man single-handedly brought down a British government and decided the fate of the Qing dynasty in China. This collective memory loss has elements of British shame at Imperial misrule and to Chinese eyes, foreign humiliation. I attempt to shed more light on this complex character.

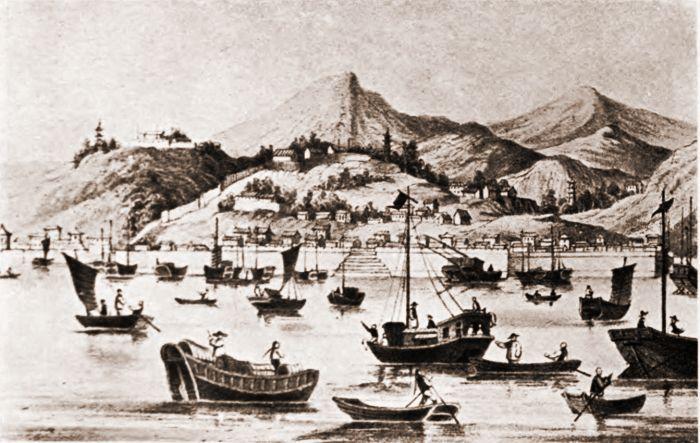

Clash of empires

In the mid-nineteenth century Britain was starting to think of itself as an Empire rather than just an international hub of ever-burgeoning free trade. Up until the governments of Disraeli, Britain was a somewhat reluctant military power. The British Empire's period of growth (1840-1900) was matched by the decline of the Qing Empire. Indeed one more striking parallel is that Queen and Empress Victoria ruled Britain 1837-1901 while Dowager Empress Cixi ruled China 1861-1908. In fact neither directly ‘ruled’ as Victoria was a constitutional monarch, and Cixi ruled through others not in her own name.

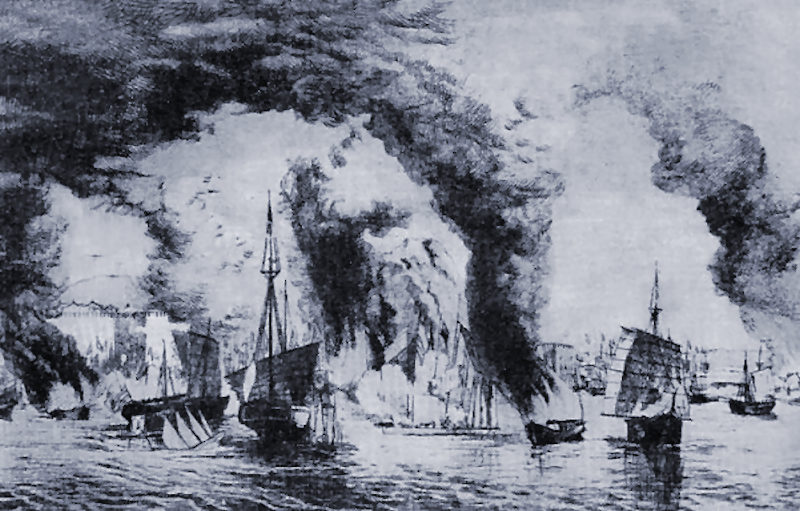

The Opium Wars between Britain and China 1839-1842 and 1856-60 mark the start of Gordon’s involvement. Many in Britain took the view that the wars were the concern of the English East India Company ➚ and not the government. People could conveniently hide behind this purely ‘commercial’ arrangement. If China was to follow the model of India then great fortunes were there to be made. Others took a different view on the opium trade. None other than future Prime Minister William Gladstone ➚ was ‘in dread of the judgment of God upon England for our national iniquity towards China’. In one of his first great Commons speeches (1840) he spoke passionately against the enterprise:

“I do not know how it can be urged as a crime against the Chinese that they refused obedience to their laws whilst residing in their own country. I am not competent to judge how long this war may last, nor how protracted may be its operations, but this I can say, that a war more unjust in its origin, a war more calculated in its progress to cover this country with disgrace, I do not know and I have not heard of.”

It was at the tail end of the 2nd Opium War in 1860 that Captain Gordon at the age of 27 first set foot in China. Charles Edward Gordon was the fourth son of a Major General, and it was made clear to him that he must follow his father into the Army. However his prickly character showed through even at Sandhurst ➚ and he had to settle for a post with the Royal Engineers ➚ rather than the more prestigious Royal Artillery regiment. After brief service at the Crimea, serving with conspicuous gallantry, he was present at the looting and burning of the Old Summer Palace (圆明园 Yuán míng yuán), Beijing - surely a low point in Anglo-Chinese relations. A chief culprit was Lord Elgin ➚, High Commissioner to China, whose father had looted Greece of its treasures, had his eyes on richer prizes in China. In Lytton Strachey ➚’s words ‘an act by which Lord Elgin, in the name of European civilization, took vengeance upon the barbarism of the East’. Gordon sent back to England one of the Emperor’s thrones, which was his share of the loot. As a junior officer he had little he could do about it; in his diary he described it as ‘wretchedly demoralizing work’ with troops ‘wild for plunder’.

As if the Opium Wars were not sufficiently destabilizing, China was also embroiled in the Taiping rebellion (1850-1864). The rebellion was a strange mixture of peasant revolt; nationalist feeling against Manchu rule and contorted Christianity. In Guangzhou, Hong Xiuquan, a lowly schoolteacher built an empire on revolutionary principles forbidding the wearing of the queue, foot-binding, prostitution, opium and promoting land reform (i.e. kicking out the landlords) and equal rights for women. A mystical experience during a probable dose of smallpox made him believe himself to have a divine mission. To the masses it was the rebellion against Manchu rule and land reform that appealed. For eleven years most of southern China was in his control from the Taiping capital at Nanjing. This was one of the worst civil wars in human history with 20 million casualties. At one stage it looked like the rebels would rule all of China.

To the Western powers, the Taiping rebellion was something of a quandary. Here was a ‘Christian’, reforming movement that already controlled southern China, should they support it? Alternatively should they support the faltering Qing dynasty that they knew would accede to any demand given sufficient pressure? It was not a clear-cut decision. Western mercenaries were employed on both sides. Indeed Henry Burgevine ➚, an American adventurer, managed to earn his money by working first for the Qing, and when dismissed by them, their enemies the Taiping rebels.

Lord Elgin was once again involved at a pivotal moment when he sailed up the Yangzi in a gunboat. His attitude is evident from the diary entry for 20th November 1858.

“It is determined therefore that tomorrow we shall set to work and demolish some of the forts that have insulted us [fired on his boats] I hope the Rebels will make some communication, and enable us to explain that we mean them no harm; but it is impossible to anticipate what these stupid Chinamen will do.”

British gunboat diplomacy meant destroy first and then explain afterwards that there had been no ill intent. Meanwhile Hong, the rebel leader, was eager for a meeting, and sent a curious message to his fellow Christian, Lord Elgin:

“Foreign younger brother from the Western Sea, heed my royal proclamation:

Let us together serve God and our Elder Brother [Jesus] and destroy the hateful insects [Qing empire]. All that happens on Earth is controlled by God, our Elder Brother, and myself.

My brother, join us joyfully, and earn incalculable rewards.”

It is difficult to see what common ground two such people could find, and the invitation was not taken up. It was as an opportunity for diplomacy that might have led to a very different course of history.

Defender of Shanghai

What sealed the allegiance of the British forces was the threat to Shanghai. Shanghai was a flourishing port run by foreigners (mainly British), by 1852 it handled half of the trade between Britain and China. The Taipings sought to capture it. After witnessing the end of the second Opium War, Captain Gordon toured China. He was then given the job (as a Royal Engineer) of building the defenses of Shanghai. Of course this really meant defending the foreign enclaves rather than the Chinese city. He saw acts of cruelty perpetrated by the Taipings, he found the use of captured boys as forced conscripts particularly distasteful. He took on the role somewhat unwillingly on the basis that it might curtail the misery of many millions of Chinese.

Shanghai was defended by a motley crew of mainly Chinese conscripts and foreign mercenaries called the ‘Ever Victorious Army’ (常胜军 cháng shèng jūn) although it did not really live up to its name. Initially led by the American Frederick Ward until his death in action in 1862, the Chinese Governor Li Hongzhang ➚ then turned to Burgevine, who was found to be untrustworthy and finally to Captain Gordon on the recommendation of the British who had officially now backed the Qing government. Gordon struggled to gain the support of this gang of highly paid foreign mercenaries who wanted to fight as individuals not in co-ordinated action under strict discipline.

It was at this time that Shanghai was receiving a deluge of refugees from the areas controlled by the Taiping. Hong Xiuquan's land reforms were not working, he had been unable to deliver his promises and the ordinary people had turned against him, many fleeing to safe havens like Shanghai. The city boundaries were guarded and blocked to all non-residents, but even so people saw no choice but to seek food and sanctuary in the city. Hardened military men such as General Sir Garnet Wolseley ➚ found the condition of the refugees appalling:

“In all such places as we had an opportunity of visiting the distress and misery of the inhabitants were beyond description. Large families were crowded together into low, small tent-shaped wigwams, constructed of reeds, through the thin sides of which the cold wind whistled at every blast from the biting north. The denizens were clothed in rags of the most loathsome kind, and huddled together for the sake of warmth. The old looked cast down and unable to work from weakness, whilst that eager expression peculiar to starvation, never to be forgotten by those who have witnessed it, was visible upon the emaciated features of the little children.”

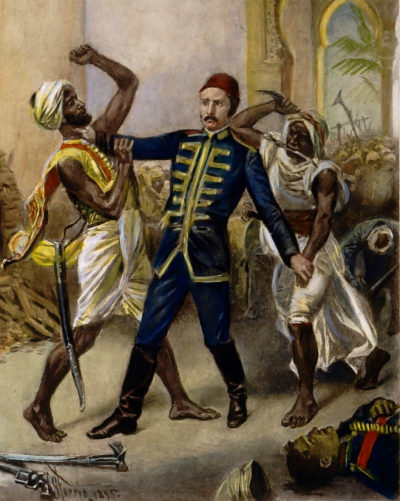

In 1863 thirty years old Gordon was given the rank of General by the Chinese, he focused his energies on the defense of the City and then took on the fight against the rebels. A driven man, who like Hong had had a religious experience, had an unbending Christian duty to all less fortunate than himself. Gordon was just the person that was needed to remodel the Army. Military discipline of the firmest kind was instilled into his soldiers, they were to be paid a salary in place of a share of the pillage (the traditional payment). They were issued with uniforms and treated with respect not brutality - unlike the Qing. In the early days of his strict regime the whole Army mutinied against the changes he had instituted, but with summary execution for desertion and selfless leadership he gradually won them over.

To Governor Li Hongzhang, one of the key players at the Qing court in Beijing, Gordon was a revelation:

“It is a direct blessing from Heaven, the coming of this British Gordon. … He is superior in manner and bearing to any of the foreigners whom I have come into contact with, and does not show outwardly that conceit which makes most of them repugnant in my sight.”

He admired Gordon’s zeal to get on with the task.

“Within two hours of his arrival he was inspecting the troops and giving orders and I could not but rejoice at the manner in which his commands were obeyed.”

Men like Li Hongzhang had come into contact with only haughty, aristocratic diplomats of the Lord Elgin mold or merchant adventurers whose sole motive was making money. Li had a personal debt to repay to Gordon, Gordon had rescued Li's brother from the rebels. Li even compared him favorably to his fellow General Zeng Guofan, which must have been a first in Anglo-Chinese relations:

“What an elixir for a heavy heart - to see this splendid Englishman fight! … If there is anything that I admire nearly as much as the superb scholarship of Zeng Guofan, it is the military qualities of this fine officer. He is a glorious fellow!”

Li's was not the only person to start changing his attitude to foreigners from ‘dogs and goats only interested in money’ to admiring their tenacity and perseverance. Wei Yuan ➚ wrote in 1844:

“Do we honestly know that among the visitors from afar are people who understand proprietary and practice righteousness, who possess knowledge of astronomy and geography, who are well versed in things material and events past and present? They are extraordinarily talented and should be considered as our good friends. How can they be called ‘barbarians’? ”

Gordon proved incorruptible, and that began to irritate Governor Li Hongzhang who used money to get his way out of almost any difficulty. Gordon took the unpopular step of stopping his troops looting, taking opium and drinking hard liquor. He banned the traditional leave given to Chinese troops to return home to help at harvest time. Mass mutiny and desertion followed with only 1700 out of 3900 remaining. Li's view became more qualified.

“With his many faults, his pride, his temper, and his never-ending demand for money - but he is a noble man, and in spite of all I have said to him or about him, I will ever think most highly of him. … He is an honest man, but difficult to get on with.”

Gordon was, of course, after money not for himself but to pay his troops and buy military equipment. It was not just high moral fiber that made Gordon stand out, he knew how best to fight a campaign. He planned expeditions using every benefit that the countryside could afford him. He went on dangerous mapping sorties to reconnoiter enemy territory. He devised his own form of gunboat to navigate the shallow creeks of the Yangzi. The use of low draft paddle steamers proved effective - the boats were greatly feared by the Taiping troops. Like the Duke of Wellington ➚, Gordon was a highly professional soldier. Looking after his troops he epitomizes the hardworking, selfless military life. Meticulous and daring he inspired idolatry among his men. He instilled courage, deportment and discipline together with superior deployment and organization.

Characteristically, he led the troops from the front, clenching his swagger stick, treating with disdain the bullets that flew about him; although he did have a concealed revolver but only used it once against a mutineer. Such brave (or stupid) behavior was bound to cause some degree of veneration, and it is said that the Taiping rebels were ordered not to shoot at the faintly smiling Englishman leading their enemies. The ‘Ever Victorious Army’ now lived up to its name, and the rebels were repeatedly beaten back towards Nanjing.

Gordon supported Li Hongzhang's larger army in their attack on Suzhou. The British guns and ammunition proved invaluable. Chinese Gordon began to see that both sides had their faults and the Taiping's abandonment of ancient rituals made them more amenable. He thought the Taiping generals were often braver and better leaders than the Qing especiallyZhōng Wáng ➚ 忠王 (1823-1864).

When Gordon negotiated the surrender of Suzhou he agreed that the rebel leaders including Zhong Wang would go unharmed. But when he discovered that they had in fact been summarily beheaded he was furious, Gordon searched everywhere for Li Hongzhang with a loaded pistol in his hand. Li tried to placate him with a share of the loot and a medal, but that of course made matters worse, Gordon resigned his command. In one of the most bizarre of scenes to contemplate, a high-ranking Chinese leader was seeking to escape the clutches of a foreigner furious because Gordon's own enemies had been killed. Li eventually successfully pleaded with him to complete the task for the sake of the Chinese people and Gordon resumed his duties. Gordon retained a high opinion of Li, he considered Li the most forward looking and liberal of the Chinese leadership. More military action followed to complete the campaign.

When offered the command, Gordon had said he would finish the ‘business’ in eighteen months. He was true to his word. He left the inevitable final capture of Nanjing to Zeng Guofan and Li Hongzhang to complete. The job was done and the Qing Emperor was enormously grateful. Gordon was sent heaps of gold in bowls carried by the emperor's men. Believing this was some sort of bribe he sent them away but only after giving the bearers a flogging for the perceived insult he had received. Such was the Emperor's wish to reward that he was then given gifts he would accept: the highest possible military title of Field Marshal and the Imperial Yellow Jacket (黄马褂 Huáng mǎ guà) with a peacock feather. This honor gave him the rare privilege of entering the Imperial Palace on horseback. A special heavy gold medal was struck by imperial decree and presented to him.

On 10th May 1864 he wrote to his mother: "I shall leave China as poor as I entered it, but with the knowledge that through my weak instrumentality upwards of eighty to one hundred thousand lives have been spared. I want no further satisfaction than this.". He correctly marked his chief contribution as training Chinese troops in the Western military manner. He had learned how to treat them ‘if we drive the Chinese into sudden reforms, they will strike and resist with the greatest obstinacy… but if we lead them we shall find them willing to a degree and most easy to manage. They like to have an option and hate having a course struck out for them as if they were of no account.’

On return to England he was fêted by the British Press who had portrayed him as a hero and ‘Chinese Gordon’ but his distaste for ‘show’ meant he quickly retreated into a fairly squalid, lonely existence at Gravesend ➚ building defenses along the Thames estuary. Who could use someone like Gordon in a military role? He had shown himself as an independent fiery spirit who was no-one but his own master - under God's guidance. His charitable work was unstinting, even the Emperor's gold medal was defaced so he could send it as an anonymous donation to a charitable appeal. An action that Gordon later admitted was one of the hardest he ever had had to do. He took some short foreign appointments but never settled down.

With his knowledge of China and close relations with leading Qing courtiers, Gordon was invited back to China in 1880 to aid the Qing in their negotiations with Russia. The Qing knew that the British feared expansion of Russian control into Afghanistan, Siberia and Mongolia. Using Gordon might prove a useful diplomatic maneuver. He was welcomed back to China by Li Hongzhang, so it is certainly incorrect to think China did not truly appreciate his previous achievements.

Gordon was no cautious diplomat. He spoke his mind. He expected his brash, non-diplomatic words to be translated for the Russians. The translator remained silent, choosing not to translate one of his outbursts. Gordon's fury at this caused the translator, visibly quaking, to spill his tea and left Gordon himself to translate the word himself by snatching a dictionary and pointing out the word ‘idiocy’ to the terrified audience of mandarins and diplomats. With such a powerful but loose cannon at his disposal Li won the day and so war with Russia was averted. Gordon set off traveling throughout China much to the concern of the British government. They must have wondered what diplomatic damage he might inadvertently do. So he was recalled, and went somewhat reluctantly back to Britain.

That was the end of ‘Chinese Gordon’ as far as travel in China. He slipped back into a quiet life in England, all but forgotten by the British people.

Even though these events are based partly on the diaries of the Chinese, Gordon's influence is now considered unimportant in Chinese history. The greatly admired Hunanese General Zeng Guofan 1811-1872 and Li Hongzhang 1823-1901 take the credit for the defeat of the Taiping rebels, but it was Gordon who had provided the military training and tactics.

In the wider Chinese context, the Tongzhi restoration (1861-1874) brought some overdue reforms through the ‘Self Strengthening Movement’ to rejuvenate the Qing dynasty. This was considered not as a wholesale adoption of Western principles but rebuilding on sound Confucian doctrine: ‘Western function and Chinese essence’. This included Zeng Guofen’s use of European style military organization to build his unit of ‘Hunan Braves’. Mao Zedong revered Zeng Guofan and Mao's military campaign against the Guomindang must surely have looked back to the exploits of Gordon.

Gordon's Murderer

When Gordon was invited by an Egyptian minister to take on the Governorship of the Sudan, this was just the sort of impossible job that Gordon relished. Sudan was prey to the slave trade run by Egypt and its then rulers - the Ottoman Empire. He, characteristically, volunteered to take only a fifth of the salary he was offered. One of his first tasks (1874) was to put down a revolt in Darfur Province (how tragic it is that peace has never been fully achieved there). In typical selfless style he mounted a camel, rode alone across 85 miles of blazing desert direct to the enemy camp. His commanding presence and single-mindedness caused the whole rebel host to obey his command to disband and so Gordon returned triumphantly to Khartoum without having fired a shot.

He then toiled to end the slave trade in Sudan but his Egyptian masters sought its continuance, and so after several hard fought attempts at reform he resigned and returned to Britain, Egypt had no use for this uncompromising and peculiar Englishman.

Some years later in 1881 the position in the Sudan became critical. An Islamist extremist Muhammad Ahmed ➚ ‘The Mad Madhi’ led a well planned and supported rebellion and so the Egyptian rulers were seeking an honorable withdrawal from Sudan. Egypt was becoming an important country because of the newly opened Suez canal ➚ built jointly with France was considered strategic for trade with India and beyond. Events in Egypt and Sudan became strategically important. An easy victory over Egypt at the battle of Tel-el-Kebir ➚ was achieved 13 September 1882 despite lukewarm support for the action in the UK parliament and the resignation of John Bright ➚. Britain and France now established joint control over Egypt. British involvement in Sudan now became extremely tricky. To withdraw and leave the Sudanese people to their fate or should they become involved militarily in their defense? Gladstone's Liberal party government was split on the issue. The Prime Minister hoped to hold his party together by taking a middle line of minimal involvement.

For some reason that still remains unclear, the Press and then the public turned to the forgotten Gordon as the one person whose knowledge and experience of the Sudan might save the day. Gladstone's government apparently agreed, although this was later denied. Gladstone's strong Christian faith and morals were somewhat in tune with that of Gordon's, but Gladstone sought compromise and negotiation where Gordon used confrontation and direct action. Gordon's instructions were too vague and these allowed him to force a resolution rather than just to report back on the situation which was the original intention.

Gordon increasingly saw himself as the hand of God's purpose. The British view of Gordon was of a righteous, humble Christian man going beyond his duty to help the inhabitants of foreign lands. He was not lauded as a military genius and as he was not a British officer in either China at the time of the Taiping Rebellion or the siege of Khartoum it is not correct to pigeon hole him as the epitome of a British Army officer. He was a tormented man with a religious fervor and a strong sense of moral right and wrong. Young men idolized him and were encouraged to follow in his footsteps as an example of selfless service to others long after his death.

Gordon arrived at Khartoum in 1884 and found an impossible situation. His clear orders were to withdraw the Egyptian and British personnel back to Egypt. True to character, he refused to leave the native Sudanese to their likely massacre at the hands of the Madhi's men. He built up defenses and petitioned the British Press to drum up support for a military contingent to aid him. It became the top political issue in the UK - whether Britain should rescue him and risk more lives. He astonished his troops by visiting the camp of the ‘Mad Madhi’ in disguise. Gladstone and his government dithered, since they did not want to get embroiled in war in Africa in a land with no perceived strategic or economic value.

The familiar heroic scene is now set, as anyone who has seen Charlton Heston's portrayal in the film ‘Khartoum ➚’ will recollect. General Gordon surveys the Nile desperately waiting for a sighting of General Wolseley ➚'s relief force on the Nile. It arrives three days late. Gordon's body is never found in the ruin of Khartoum. The determination of Gordon to hang on at Khartoum and do his duty by the Sudanese people leads to not just his heroic death but to a revision to the concept of ‘British Empire’ - not exploitation but saving the local people from tyranny and war.

So it was that Prime Minister Gladstone was widely portrayed, with some justification, as Gordon's murderer. In the Press ‘The Spectator’ thundered “a grave misfortune has fallen on civilization”. Amongst the strongest critics was Queen Victoria who deliberately sent Gladstone an un-encoded telegram so that all should know of her displeasure ‘These News from Khartoum are frightful and to think that all this might have been prevented and many precious lives saved by earlier action is too fearful’ .

Gladstone's reply to her is a master class in diplomatic belittlement.

“Mr Gladstone does not presume to estimate the means of judgment possessed by Your Majesty, but so far as his information and recollection go, he is not altogether able to follow the conclusion which Your Majesty has pleased thus to announce.”

Gladstone's administration limped on for another four months in command of a mortally wounded government. Disraeli's view of an Empire spreading Enlightenment across the globe won the upper hand and jingoistic supporters sought to emulate Gordon's heroism.

Legacy

For the next fifty years Gordon was revered as a ‘Christian martyr’ and a ‘soldier for enlightenment’. Dotted over the British Empire, schools and towns were named in his honor. Lytton Strachey ➚’s ‘warts and all’ biography was the first to reveal the troubled spirit that underlay the overly heroic image. His dramatic end at Khartoum was hi-jacked for those whose political aims promoted Imperial conquest. But judging by his life, Gordon was no conquering nationalist, he did not conquer a single square mile of land for the Queen, and worked mainly for foreign governments and not the British Army. Now that the Imperial era is viewed with regret and distaste, Gordon's exploits which have for so long been associated with Empire no longer receive any attention.

In China, Gordon is dismissed as yet another foreign mercenary who exploited the country's weakness at the time. But, surely all the people he came across must have revised their views of the ‘foreign devils’. Here indeed was a fiery spirit but not one that exploited for monetary gain. The lessons of his success with the ‘Ever Victorious Army’ influenced all subsequent military campaigns, as European military tactics and weaponry were adopted in China.

Although Gordon’s (and by proxy Britain’s) efforts may have clinched victory in the Taiping Rebellion, the effect on Chinese politics was far-reaching. Trade with China became dominated by Britain, about two thirds of all foreign trade was between these two countries from 1860 to 1900 (the chief commodities opium and cotton). Li Hongzhang now had a modern army and a southern power base at his disposal, he was a match even for the Qing emperors, Li became the first of many warlords whose personal power-base invited foreign exploitation. After the ‘Self Strengthening Movement’ faltered, Dowager Empress Cixi turned back to more traditional Chinese solutions. Li Hongzhang negotiated with the Japanese but as these talks led on to the disastrous Sino-Japanese War and the fall of the Qing, history marks him out as a villain who failed to modernize quickly enough to meet the foreign threats.

On the monument to the defenders of Shanghai, on the Bund, Gordon is not even mentioned although the other foreigners who served are commemorated. I know of no monument to Gordon in China. Perhaps it is now time that this oversight should be rectified? However from all what we know of his character he would surely have been affronted by the idea of a memorial, and would have wished instead that the money for such a monument should go to charity.