Opium Wars with China 1839-1860

If you want to pick an event that marked the change of the Chinese Imperial attitude towards the rest of the world you could well pick the episode of the Opium Wars. It marked the beginning of what is regarded as China's ‘century of humiliation’ 1842-1949.

China since the Ming dynasty had turned inward and could see no benefit to trading with the barbarians who came from far away; they considered that they had all necessary goods in abundance, previous dealings with Europeans had proved them belligerent and untrustworthy. Britain since the Napoleonic wars (1803-15) ➚ had ruled the waves and saw herself as the chief advocate for Free Trade ➚ amongst the nations. These incompatible world views came to their inevitable conflict over the unlikeliest of goods: opium.

Failed British Missions

The British felt that they had done everything they could reasonably have done to introduce free trade with China during the period of pre-1700 and 18 century contacts. In 1793 Lord Macartney went as far he could to negotiate a trade agreement with Qing Emperor Qianlong at Chengde. His refusal to show due deference to the Emperor with a kowtow proved a diplomatic stumbling block and also neatly symbolized Britain's self-estimation as an equal not a subordinate nation. There had been earlier unsuccessful missions dating back as far as 1553, a trend was continued. China had a stranglehold on the tea trade that had grown from 6 million to 16 million taels of silver in 20 years. Britain was by then buying 15% of all tea grown in China producing a very useful income in silver for the struggling Qing regime. Yet Macartney achieved minimal access to the Emperor and the mission was unsuccessful, although it is said that they came away with tea plants that helped found the Indian tea industry which eventually cost China dearly in lost revenue. The Emperor viewed the British as yet another barbarian state of little consequence trying to inveigle higher prestige from China. The modern industrial and technical gifts Macartney gave the Emperor were not seen as having any particular purpose, just interesting toys. China had all it needed and had been run much the same for centuries, there was no need to change. In return the Emperor gave his visitors a priceless jade Ruyi ornament which was not perceived by them to be of much value.

The British went away frustrated, they were still forced to carry out their limited business at the only port they were allowed to trade at: Guangzhou (Canton) under the harsh and strict control of the Chinese officials who supervised all business (the cohongs ➚). Europeans were not allowed onshore, and all negotiations had to go through, usually corrupt, middle men. They were only allowed to trade if sufficiently submissive and obedient and had to accept arbitrary taxes imposed on top of agreed terms. Trade was only permitted during a short season, the rest of the time the foreigners had to leave, and most waited at Macau for the next trading opportunity. Chinese were banned from learning European languages and Europeans from learning Chinese - the authorities sought to limit contact to the barest minimum. Europeans and Americans were subject to Chinese law and some (as in the case of the ships ‘Emily’ and ‘Lady Hughes ➚’) Europeans were put to death according to Chinese laws for apparently just unfortunate accidents. The rest of the world wanted China's tea, silks, porcelain and spices, while China only wanted silver in return; she did not want any of the mass produced textiles and industrial goods Europe could now offer in exchange. At the time in China there was high unemployment and so the cost of goods in China was driven very low and even Manchester cloth ➚ struggled to establish itself as a competitive product.

Entrenched attitudes

The Chinese saw the British as like a peepal tree ➚ – a tree that sends out roots that spread and smother everything. The official attitude to these foreign barbarians is summed up in this court maxim:

“The barbarians are like beasts, and not to be ruled on the same principles as citizens. Were any one to attempt controlling them by the great maxims of reason, it would tend to nothing but confusion. The ancient kings well understood this, and accordingly ruled barbarians by misrule. Therefore to rule barbarians by misrule is the true and the best way of ruling them.”

The Chinese Emperor and his advisers shared this negative view:

“(The English) are not worth attending to… An insignificant and detestable race… in the class of dogs and horses.”

The foreigners got the message, this is the report of Sir John Davis, a former governor of Hong Kong.

“The rulers of China consider foreigners fair game; they have no sympathy with them, and, what is more, they diligently and systematically labor to destroy all sympathy on the part of their subjects, by representing the strangers to them in every light that is the most contemptible and odious. There is an annual edict or proclamation displayed at Canton at the commencement of the commercial season, accusing the foreigners of the most horrible practices, and desiring the people to have as little to say to them as possible.”

At heart were incompatible underlying philosophies. Britain saw mercantile effort as the supreme achievement, it was the way anyone could rise to wealth and influence. In China the merchant class was low in public estimation compared to the philosophers, public servants and even farmers who were all seen as serving a more useful purpose. In China, the ambition to make yourself rich on the back of other's work was despised.

Somerset Maugham in his book ‘On a Chinese Screen’ sets out the views of a Chinese philosopher he visited in the early 1930s:

“What is the reason for which you deem yourselves our betters? Have you excelled us in arts or letters? Have our thinkers been less profound than yours? Has our civilisation been less elaborate, less complicated, less refined than yours? Why, when you lived in caves and clothed yourselves with skins we were a cultured people. Do you know that we tried an experiment which is unique in the history of the world? We sought to rule this great country not by force, but by wisdom. And for centuries we succeeded. Then why does the white man despise the yellow? Shall I tell you? Because he has invented the machine gun. That is your superiority. We are a defenceless horde and you can blow us into eternity. You have shattered the dream of our philosophers that the world could be governed by the power of law and order. And now you are teaching our young men your secret. You have thrust your hideous inventions upon us. Do you not know that we have a genius for mechanics? Do you not know that there are in this country four hundred millions of the most practical and industrious people in the world? Do you think it will take us long to learn? And what will become of your superiority when the yellow man can make as good guns as the white and fire them as straight? You have appealed to the machine gun and by the machine gun shall you be judged.”

The Opium Trade

With a burgeoning Indian Empire ➚, generating vast amounts of money, the British were on the doorstep of China, and they must have hoped to repeat the successful Indian business model there. Britain turned to goods that were so highly prized that Chinese officials could be bribed to turn a blind eye to trade in them; this was opium. For centuries China had imported opium from northern India by way of overland transport through Yunnan. Limited amounts of opium were also grown in China for centuries, at least as long ago as the Tang dynasty, however it was widely adulterated with linseed oil and other substances, the Indian opium was considered higher quality, particularly from Madhya Pradesh ➚. The Chinese came to believe that this powerful drug must contain some potent additional substance, rumors suggested that it was made from poppies mixed with the putrefied flesh of eagles and men. The opium trade from India was not started by the British, the Portuguese had started making vast profits from it in the late 16th century. When Britain took control of India, she inherited the existing trade in opium and then greatly expanded it. The silver from the opium crop was then used to buy Chinese goods that were then shipped back to Europe.

In 1796 China imposed a ban on opium import, really to suppress trade and protect the Chinese producers of opium rather than to discourage consumption. Indeed the tax on opium sales was a welcome source of income. To protect its tea trade Britain ceased direct open trade in opium, instead selling it to Indian middlemen who then sold it on. With the end of Spanish control of the American silver mines the supply of silver in China became restricted and opium came to be used as an alternative currency in the southern provinces. In 1829 Britain exported $21,000,000 of goods to China of which opium accounted for half the value. In the same year the U.S. exported $4,000,000 in goods with a quarter of that in opium. A large increase in the trade came about in 1834 when the English East India Company had its monopoly in trade broken; small shipping firms could now muscle in on the lucrative trade without restriction. The escalation of the trade dispute came with the appointment of Lord Napier ➚in 1833 as ‘Superintendent of Trade’ to represent traders from all nations. The Chinese did not want to deal with a single representative it was easier to deal with individual traders and he was told to leave. He refused and a blockade followed. Napier eventually had to retreat to Macau which was also blockaded by the Chinese, famine set in and many had to abandon the island and take refuge on ships. Napier died of fever on 11th Oct. 1834 and he was the first to suggest Hong Kong as a suitable British colonial outpost.

At this time China thought a solution would be to grow opium in the south west and so undercut any price paid for imported Indian opium. Expeditions were sent to find the poppies in India but the Taiping and other rebellions in the areas for cultivation led to the abandonment of this initiative.

The effects of opium

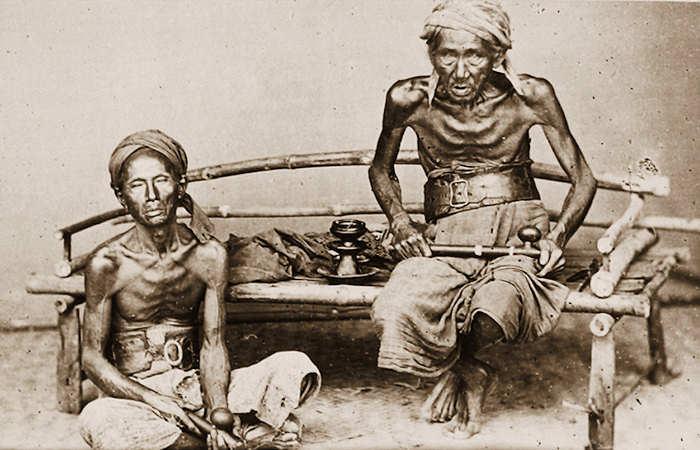

At this time opium and other narcotics were not seen as the evil thing they are today. Educated and refined people in England took a nightly dose of opium (in th form of laudanum ➚) to help them sleep. Although some people became addicted it was not seen as any worse than alcohol. Jardine Mattheson took view that opium was ‘not a curse but a comfort and a benefit to the hard-working Chinese’. So opiates were not considered in Europe as an awfully bad thing, if taken in moderation, therefore trade in opium was widely seen like alcohol - unfortunate, but not evil. However in China opium had had a crippling effect on many people, particularly government officials, and so it was banned in 1813. The ban had limited effect in the coastal states. Smugglers and criminal gangs managed to circumvent the law and maintain a steady supply of the drug. The Manchu government saw its tax income from trade in tea and silk decline as the illicit trade in opium grew enormously.

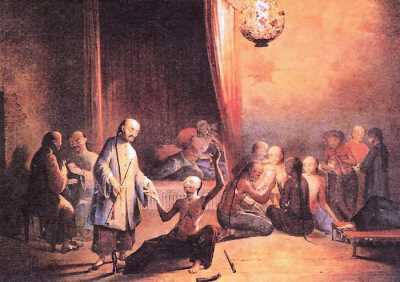

Mr. C.V.A. Peel describes a visit to an opium den in the late 19th century:

“A Chinese opium den was a surprise to me and very different from what I had expected. On entering one night a house brilliantly illuminated outside with red and gold paint and dozens of Chinese lanterns, I was at once met by a most courteous gentleman speaking a little ‘pidgin’ English, who led me up into a large well lighted room, the walls of which were beautifully decorated with red silk, embroidered with gold. The room was crowded with Chinamen, eating, sipping tea, listening to a large orchestra and flirting with a number of girls with horribly white painted cheeks, red lips, no eyebrows, and deformed feet. I was made to partake of some very weak tea, cakes, pomeloe, and other fruits. I was, in fact, most hospitably entertained. I ventured to remark to my host that it was a very beautiful room”.

“My host next prepared or ‘cooked’ an opium pipe for me. The pipe consists of a bamboo about a foot long, with a hole three quarters of the way down, into which is pushed a porcelain bowl, which is very porous, and in the center of which there is a small hole not much bigger than a large pin-hole. The opium, which is viscous like treacle, is kept in a small tin box, into which is dipped a skewer-like instrument. What opium this implement brings up is held in a small spirit lamp resting on a table between two smoking divans on which smokers recline at full length whilst enjoying this fascinating drug”.

“When the opium on the skewer begins to bubble it is smeared on to the surface of the pipe bowl, and some is inserted into the pin-hole, the skewer being twisted round in order that the hole may not be entirely clogged up. The pipe is then cooked and ready to be smoked ; it is held bowl downwards over the flame of the spirit lamp all the time the opium is being inhaled. It takes at least ten pipes to make one feel drowsy”.

Massacres of Christians by the Heathen Chinese pp. 354-355.

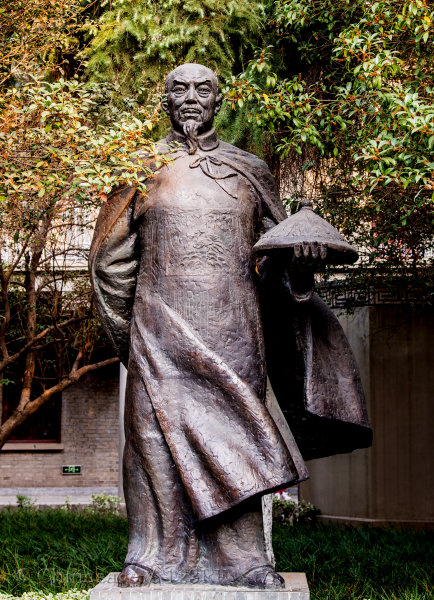

Suppression of Opium Trade

In 1838 Commissioner Lin Zexu ➚ was sent by the Emperor to stamp out the opium trade in Guangzhou. The reaction by Britain was to circumvent the ban. Lin Zexu had learned that England was ruled by a young girl (Queen Victoria), and the Emperor sent ‘instructions’ to her demanding that she must suppress the trade. The letter never reached her, and would have been ignored if it had. After being forced offshore the opium traders still managed to sell their opium by using a flotilla of small boats at night, Lin then imposed a blockade to starve them out. The dispute became entangled with another issue after the death of a Chinese seaman Lin Weixi; the Chinese demanded the British sailor who had beaten him to death to be handed over to Chinese justice which would have meant certain execution. The British investigated and found Lin Weixi had been beaten with sticks by sailors and could find no grounds for any particular sailor to be implicated and in any case the charge would have been manslaughter rather than murder. The dispute escalated between Lin Zexu and Captain Elliot, with Lin Zexu demanding Elliot to stand trial if the culprit was not handed over. The British were able to take a high moral stance on the grounds of defense against barbaric Chinese justice; allowing them to feel virtuous even if they could not defend their trade in opium. There was intense public debate back in the UK over this issue. A wax effigy of Lin and his wife was exhibited at Madame Tussauds ➚ in London with the title ‘Author of the China war’.

The blockade of Macau and Guangzhou was lifted by force, in September 1839 HMS Volage ➚ fired on Chinese war-junks and the war began. The Emperor grew annoyed with Lin Zexu's apparent prevarication and replaced him with the Manchu Qishan ➚, a cousin of the Emperor; this proved equally unwise. Lin Zexu's approach was to give no ground and no compromise was possible with him, Qishan on the other-hand quickly negotiated an apparent permanent concession of giving away the barely inhabited Hong Kong island at the Convention of Chuenpee ➚ (January 1841). When the Emperor learned of this unsanctioned deal, Qishan was removed from office and banished. The British side were not happy with the deal either, Queen Victoria herself wrote “The Chinese business vexes us much… All we wanted might have been got, if it had not been for the unaccountably strange conduct of Charles Elliot… who completely disobeyed his instructions and tried to get the lowest terms he could.”

Even Lin Zexu later admitted in his memoirs that the Emperor's intervention came too late; if it had come twenty or ten years earlier the opium addiction could have been controlled. By 1840 many traders at Guangzhou had become rich from the trade, indeed it was said that anyone traveling from Guangdong province was under suspicion of being an opium dealer. The bribes and cuts through handling the drug formed a huge network of traders and officials complicit in the trade, and their loyalties could not be trusted. Before hostilities commenced, Guangzhou traders chose to support the foreign barbarians bringing valuable goods rather than a remote Emperor of foreign Manchu blood imposing his will. Southern China had for centuries been allowed to trade quietly on its own terms without much Imperial control.

Some Canton traders became immensely rich. The most powerful was the Chinese merchant known as Howqua ➚ - real name Wu Bingjian (1769-1843) when his warehouse burned down in 1822 it is said the melted silver formed a stream two miles long.

British naval attacks

Open hostilities commenced and Lord Palmerston ➚ responded by sending gun-boats to ostensibly protect British ships and sailors. This force in 1840 sought to negotiate with the Emperor a solution to hostilities, when they were rebuffed, the superior British naval force attacked key ports along the coast (Fuzhou, Xiamen, Ningbo and Tianjin) and then threatened the major city of Nanjing. A great weakness of the Chinese position was that they repeatedly gave false accounts of easy victories over the British. This was partly because a Chinese commander would gain promotion for such a victory, and what actually happened was difficult to know with any certainty. And so the Chinese leadership were fed a diet of misleading and outrageously inventive tales. The British force grew to 10,000 men and 14 steamships. The force sailed up the Eastern coast and took Dinghai, Zhejiang ➚. On many occasions the Chinese defense was half-hearted with abandonment of positions after only initial shots fired. Britain's main advantage were the shallow-draft steamers that could navigate narrow waterways close to Chinese towns. At one time the honorable side of the British idea of warfare was exposed when they had heard that Admiral Guan ‘had lost his button’ after fighting bravely but in vain, they searched the battlefield and returned a ‘button’ to the Chinese. In fact ‘losing a button’ had the meaning that the Admiral had been demoted by the Emperor because of his defeat.

Perhaps the propaganda pamphlet written by Marjoribanks ‘A brief Sketch of British Character and Policy’ ➚ had had its effect, many Han Chinese blamed the Manchu overlords as much as the British for their predicament.

“The people of China are highly intelligent, industrious, and prosperous; but they are not the only people in the World that are so. Ignorant men have sometimes foolishly taught, that all that is good is centered in China, but that the rest of the earth is worthless. – How vain and childish is the man who reasons thus!– If he had visited other countries, he would have discovered, that Heaven had in its bounty and mercy bestowed manifold blessings on many other regions of the earth. In England, the people live in tranquility; their persons and property are protected by the laws; their religion inculcates peace upon earth and good will towards all men; they have arrived at a wonderful state of improvement in arts and science, and in the cultivation of all those means which serve to civilize mankind. They are feared in times of war, and honored in times of peace. There is no country with which it is more the interest of China to remain on terms of friendly intercourse than England. It carries on a great and lucrative commerce with this Empire, and the confines of its Indian dominions almost border upon those of China. One river which rises in Yunnan flows through a portion of the British territory.” (The Canton Register July 18, 1832)

The naval force went on to take the city of Ningbo easily and then Shanghai and most of Zhejiang province. Some measure of the incompetence of the Chinese defense can be seen from the behavior of the Emperor's cousin Prince Yijing ➚. He was appointed General and at once he employed a team of learned scholars to write up their forthcoming, supposedly inevitable, victory. All the Chinese age old war tactics failed to work, the British knew about such things as fire boats and night attacks; so Britain gained an easy victory. An attempt to retake Ningbo ended with many Chinese deaths and a humiliating defeat. Superstition paid a major part in the attack, the tiger was considered the totem that would defeat the British so the attack took place on a tiger day in a tiger month at a tiger hour with some soldiers in tiger costumes.

The British then sailed up the Yangzi River with the aim of splitting off southern from northern China and seized the important city of Zhenjiang and threatened the major city of Nanjing. The Chinese response was greatly hampered by a major flood on the Yellow River in August 1841 around Kaifeng resulting in the loss of millions of lives - by comparison the British ‘pirate’ problem was insignificant. In the opium conflict about 20,000 Chinese were killed or injured but tellingly only 69 were killed and 451 wounded amongst the British. More British died of disease than in the conflict.

Some British troops were captured. This included Captain Peter Anstruthers of the Madras Horse Artillery. This large and colorful character had been captured while out sketching the countryside on Zhoushan Island. He resisted threats of torture and had long conversations with Wei Yuan ➚, a renowned reformist scholar. The information he gave may have changed Chinese dismissive attitudes to these barbarians. Wei communicated with Lin Zexu and put together a book ‘A brief account of England’. Wei saw the threat and proposed that China must beef up its naval defenses. Unfortunately Wei became embroiled in the Taiping Rebellion and his ideas contained in 海国图志 Hǎi guó tú zhì 'Illustrated Treatise on the Maritime Kingdoms' never became official policy.

Chinese surrender

The Emperor Daoguang capitulated and at the Treaty of Nanjing ➚ (1842) acceded to British demands, giving them Hong Kong island in perpetuity and free access to ports including Shanghai. The foreign enclaves in these treaty ports became subject to foreign law (extra-territoriality) and not Chinese law. Trade in opium however remained illegal; Emperor Daoguang told the British “I can not prevent the introduction of the flowing poison; gain-seeking and corrupt men will, for profit and sensuality, defeat my wishes; but nothing will induce me to derive a revenue from the vice and misery of my people”. America keen not to be left out of trade agreements sent a mission headed by Caleb Cushing ➚ and exacted similar concessions from China soon after in 1843.

When the British parliament came to vote on the Opium War on April 7th 1840 (only after hostilities had begun) William Ewart Gladstone ➚ spoke passionately about the shamefulness of the war and Palmerston only won by seven votes. Before the conflict, the Rev. A.S. Thelwall had published a book ‘The Iniquities of the Opium Trade with China’ in 1839, which caused quite a stir, so it is unfair to implicate all British people with the ‘crime’ of the trade. The Times of London came out against this ‘miserable war’. It is significant that Sir George Staunton ➚, who served as a page boy in the ill-fated MacCartney embassy of 1794 spoke in favor of the war, even though he had been given a gift by the hands of the Emperor himself.

A little quoted benefit of the conflict is that the British systematically cleared the coast of the pirates that had been a menace to Chinese and foreign shipping for centuries.

The Second Opium War

The deal did not bring lasting peace. Local Chinese officials reacted to the humiliation of the treaty by not sticking to the letter of the agreement and they were dismayed that the opium trade continued unabated - the new Emperor Xianfeng (1851-61) even became an opium addict. In December 1847 six British citizens were murdered near Guangzhou, exciting much anger. Local Chinese continued their opposition to foreigners in the new treaty ports. Some were attacked with stones and on one occasion a baker supplied bread poisoned with arsenic. Using the excuse of the disputed Chinese boarding of a British ship the ’Arrow’ ➚ in 1856, UK Prime Minister Lord Palmerston sent back the gun-boats ➚. The Taiping Rebellion had by then taken hold in southern China and Britain found itself having to deal with two regimes in China. British interest at the time was not really focused on China, for the Crimean War ➚ (1853-56) had started and Russia was the chief threat and enemy; the Great Game ➚ with Russia over control of Central Asia was in full play. Commissioner Ye Mingchen ➚ had been appointed as governor of Guangdong. The first flare-up occurred in December 1857 when an Anglo-French force captured Guangzhou and Ye Mingchen who was sent as captive to India where he died in 1859. In the Second Opium War the British had French support (America, France, Germany, Japan were all keen to open up trade with China) and once more attacked Tianjin and the Dagu forts ➚ Taku WG that protected Beijing. The forts had been extensively rebuilt and strengthened since the first war and held off an initial British assault but soon fell to a larger combined force. The result was more Chinese humiliation, the European weaponry was far superior to anything the Chinese had to offer.

The general view of the foreign nations of China throughout this time has been summed by the philosopher Bertrand Russell ➚:

The Chinese are a great nation… They will not consent to adopt our vices in order to acquire military strength but they are willing to adopt our virtues in order to advance in wisdom. I think they are the only people in the world who quite genuinely believe that wisdom is more precious than rubies. That is why the West regards them as uncivilized.

Further Chinese concessions

The Treaty of Tianjin ➚ (1858) imposed more onerous conditions on China including the legalization of the opium trade and the impositions of an import tax on it. This gave the Chinese government considerably tax revenue. The foreign merchants were no longer to be insultingly referred to as ‘barbarians’. Emperor Xianfeng still refused to deal directly with the Anglo-French forces. He fled to Mongolia and the expeditionary Anglo-French force burnt his Summer Palace to the ground after looting it. The choice of the Summer Palace was deliberate, they wanted to send a clear message to the Emperor not the ordinary people, so destroying a lavish pleasure palace would cause less hardship than other targets. The pretext for the raid was that a peace mission including Henry Loch ➚; Harry Parkes ➚ and some journalists had been incarcerated and tortured with several members dying as a result. The Europeans were impressed by the bravery of the ‘Tartars’ (Manchu) forces even though Manchu guns offered little threat. Sympathy for the British cause was stirred up by the case of Private John Moyse ➚ who was beheaded because he refused to kowtow to a Chinese General. A Pekingese dog ➚ was captured and presented to Queen Victoria who insensitively named it ‘Looty ➚’. Lord Elgin entered Beijing and forced China to sign the Convention of Beijing ➚ in 1860 which gave away yet more control over trade to the Europeans. Inland China was opened up to foreign Christian missionaries. Illegal home production of opium burgeoned, by 1880 it had begun to supplant imported opium. The opium trade continued with up to 10% of the population smoking opium by 1900, with a high proportion of low ranking officials among the addicts. Even Dowager Empress Cixi took opium, and in her edict of 1906 banning the taking of opium absolved all those over sixty years old (including herself) from the law.

Not all Europeans rejoiced at the destruction of the Summer Palace, no less a writer than Victor Hugo ➚ lamented the loss.

Once in a distant corner of the world, there was a great wonder, a wonder known as the Summer Palace. Everything born of the imagination of an almost superhuman people was there… Build a dream of marble, of jade and bronze; cover it with porcelain; cover it with precious stones; drape it in silk; make of it a sanctuary, a harem, a citadel; fill it with gods and monsters; varnish it, enamel it, gild it, adorn it; let poet-architects build the thousand and one dreams of the thousand and one nights; add gardens and ponds, fountains of water and foam, swans, ibises and peacocks, a dazzling cavern of the human imaginations…

It had taken the patient work of generations to create it, and people spoke of the Parthenon of Greece, the Pyramids of Egypt, the Coliseum of Rome, the Summer Palace of the Orient… This wonder is no more.

There came a day when two bandits entered that Palace. One plundered it, the other put it to the torch. Involved in this we find the name of Elgin ➚, which fatally reminds us of the Parthenon. What one Elgin ➚ began at the Parthenon has now been repeated at the Summer Place, but more completely, such that nothing at all remains. All the treasures of all our cathedrals taken together would not have equaled this formidable and splendid museum of the Orient. A great exploit, a true godsend! One of the conquerors filled his pockets, the other his coffers, and the two returned to Europe arm in arm, in laughter.

We Europeans are civilized, and to us the Chinese are barbarians. Here is what civilization has done to barbarism!

History shall call one of these bandits France, the other England. But I protest!

The French Empire has pocketed half the spoils of this victory, and today, with a proprietor's naiveté, it displays the splendid bric-a-brac of the Summer Palace. But I hope the day will come when France, cleansed and delivered, will return its booty to despoiled China.

Until then, when we have is theft, and two thieves.

I take note.

Such Sir, is the degree of approbation I bestow upon the China expedition.

Victor Hugo

Even those taking part had misgivings, General Charles Gordon later to become known as ‘Chinese Gordon’ from his efforts in the Taiping Rebellion wrote a letter to his mother:

“…You can scarcely imagine the beauty and magnificence of the places we burnt. It made one’s heart sore to burn them; in fact these palaces were so large, and we were so pressed for time, that we could not plunder them carefully. Quantities of gold ornaments were burnt, considered as brass. It was wretchedly demoralizing work for an army. Everybody was wild for plunder.”

Within China the world view changed, China was not the only major nation in the world. Other nations were not just irritating gnats biting the central behemoth. China had to understand foreign perspectives and no longer ignore all things non-Chinese.

Taiping Rebellion context

The second Opium War took place at the same time as the Taiping Rebellion (1850-64) and China's weakness must be seen as a sideshow compared to this devastating Civil War. In 1860 one third of China (and the most prosperous parts) were under Taiping control. The foreigners could threaten to support the Taiping rebels in the power play against the Qing Imperial system. Indeed foreign arms and tactical support was being provided to both sides of the Rebellion. The two Opium Wars compared to the Taiping Rebellions were skirmishes. In the 2nd Opium War 2,000 Allies (British, American and French) were killed compared to 30,000 Chinese. The Taiping rebellion cost something like 25,000,000 Chinese lives.

Kicking the habit

The insatiable demand for the drug continued well after the Opium wars. In 1880 opium grown in China started to take over from imported Indian sources. By 1917 China was self sufficient with most of the crop grown in the south-west particularly Sichuan and Yunnan. During the Japanese occupation of China (1937-45) opium was supplied by the Japanese as part of efforts to subdue dissent. The Republican government continued to treat the opium trade as a vital source of revenue. It was only when the Peoples Republic of China was declared in 1949 that a comprehensive plan was introduced to end the misery of millions. Addicts were forcibly put on a plan to stop their addiction and opium farmers in China were forced to grow alternative crops. Any opium dealer faced the death penalty. These measures quickly brought an end to the problem in China in the 1950s.